Everything you never wanted to know about burnout

A panel of people with experience in occupational burnout share their professional and personal perspectives on its causes, effects, and how it can be avoided

Crunch, working conditions, and mental health have been topics of frequent discussion in the games industry for years. At last month's Game Developers Conference, a panel of personal and professional experts discussed the subject at length.

Take This clinical director Dr. Raffael Boccamazzo led the session with an overview of occupational burnout, detailing how the medical community assesses it and what factors play into it.

He was followed by Spry Fox lead game designer Alicia Fortier, Blizzard Entertainment lead content designer Osama Dorias, and The Outsiders lead UX designer Anna Brandberg sharing their own experiences with occupation burnout and what they've learned from the ordeal.

What is burnout?

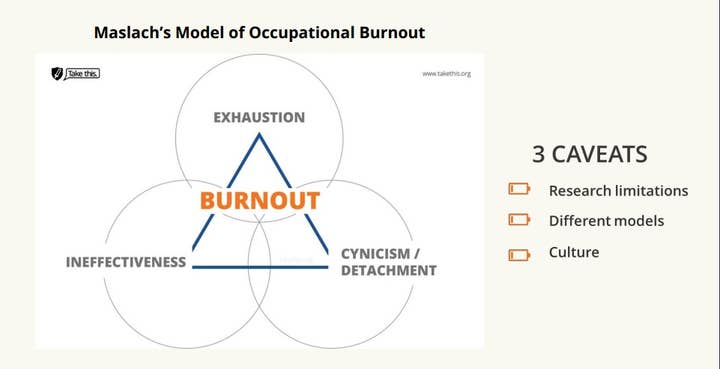

Under Maslach's model of occupational burnout – which Dr. Boccamazzo called the most commonly used model and a basis for the World Health Organization's definition of the affliction – it is "a chronic syndrome due to exposure to overwhelming long-term stress in the workplace" with three main criteria, all of which have to be present for "full-on burnout."

Exhaustion

"It's more than just being physically tired and you take a few days off and it goes away," Boccamazzo said. "We're talking about a kind of pervasive, bone-deep, soul-crushing cognitive and emotional weariness that paradoxically interferes with our ability to rest and recover."

Ineffectiveness

"It's not just self-doubt or impostor syndrome. With burnout, our effectiveness is measurably decreased. And not once or twice; our performance is consistently not as good over a long time."

Cynicism or Personal Detachment

"With that, we might see mood shifts, like anger at yourself or other people around you. You might see cognitive shifts, like a lack of investment. We might force ourselves to physically do the work, albeit badly, but we're mentally checked out, and over a long period of time."

Boccamazzo offered a number of caveats, specifically that there are other models of burnouts, and most research in the field is based on service industries, like medicine or teaching. Additionally, some research only focuses on one or two of the attributes, and there are cultural differences in how distress is expressed, so symptoms are not necessarily uniform around the world.

Ultimately, if anyone believes they're experiencing chronic effects from workplace-related stress, he recommended reaching out to qualified professionals in one's area who specialize in workplace stress.

Maslach's model identifies six contributing factors to this burnout:

1. Work load - Are you consistently given more work than you can realistically do? Scope creep can add to this, as can layoffs and the resulting job consolidation.

2. Reward - Are you rewarded properly for your contributions? This is not just pay, but also recognition in personally meaningful ways. As Boccamazzo said, "Pizza parties don't cut it."

3. Control - Can you affect how you work and what you work on? Are your tasks dictated from the top down, or do you have input on things like your schedule, where you work from, and so on?

4. Community - Do people have a sense of belonging at work? Or are there divisions, subtle or overt, based on full-time or contractor status, identity, disability status, job role, or even department? Anything that reduces belonging contributes to burnout.

5. Fairness - Are the policies, rules, procedures, promotions and disciplinary measures applied equally to everyone, or are there certain people who seem to be disproportionately impacted?

6. Values - Are the company's goals in alignment with your values as an employee, and is the company consistently enacting its stated values? Does the company talk about putting people first but its actions prioritize profits instead?

Boccamazzo underscored that in many cases, these problems are beyond the burning out individual's ability to fix.

"Every factor here is driven by leadership and so is the change which is needed at a systemic level to fight burnout"Rafeal Boccamazzo

"I would also challenge each of you to look at any one of these factors and find any one of them where individual self-care fixes the problem… Every factor here is driven by leadership and so is the change which is needed at a systemic level to fight burnout," he said.

"When it comes to occupational burnout, focusing on individual resilience and self-care without changing the system is a bit like suggesting people just need to learn how to swim better in a leaky boat. Learning to swim is great, but we have to fix the boat."

He noted that occupation burnout has been linked to increased turnover, long-term medical absences, absenteeism, and presenteeism, which is when people are at work but accomplishing virtually nothing.

What's more, when burned out people leave, Boccamazzo said research shows they are twice as likely to take other people with them.

That's to say nothing of the reputational costs ("burned out employees talk," he noted) or the impact on creativity when people don't feel safe or supported enough to voice nascent ideas.

"Whether you want to look at burnout from a moral and human issue – and I hope you do – or you want to look at it from a perspective of cost and product, there is no shortage of reasons to take it seriously and address it," Boccamazzo said.

Pressure and nuance

Alicia Fortier's portion of the presentation recounted her own experience with burnout, contrasting the various pressures she felt to drive herself to burnout, alongside a more nuanced angle on the situation she reminds herself about now to keep things in perspective.

Pressure - I need to prove myself constantly. Anything I don't know is a flaw.

During school, Fortier said she regularly did all-nighters, participated in game jams, and worked to get high grades, so much so that when she started her career, she was already exhausted. Despite that, she didn't slow down.

"I wanted to learn, I wanted to give, and I wanted to prove myself and my place here," Fortier said. "And that meant – I'm sure like some of you – I had no sense of self-preservation and how to guard myself."

Nuance - The reality is you learn with time, practice, and experience, and there are literally infinite things to learn.

"What's important to learn to develop is evaluating when is enough for now," Fortier said. "Be patient with yourself. Give yourself grace with where you are now and what you still have to learn."

"To put in that extra effort, what are you sacrificing? Your sleep, your friends, your family?"Alicia Fortier

She noted that developers often say making a game is a marathon and not a sprint, so if you're going full-out right from the start, how do you ramp up from there and what do you have left?

"I invite you to think critically about where you spend your energy," she said. "What are you learning and how much extra effort do you [need] to learn just a little more? And to put in that extra effort, what are you sacrificing? Your sleep, your friends, your family? For how long will you sacrifice them?"

Fortier told a story about one day in 2016 when she was working on a project that pivoted and she stayed late to handle the required re-working. In doing so she missed a vet appointment to say goodbye to the family cat, and only realized it afterward. She later found out the appointment had been delayed for unrelated reasons, so she was able to say her goodbyes a few days later after all.

Pressure: If work is being assigned to me, I should be able to complete it all as requested.

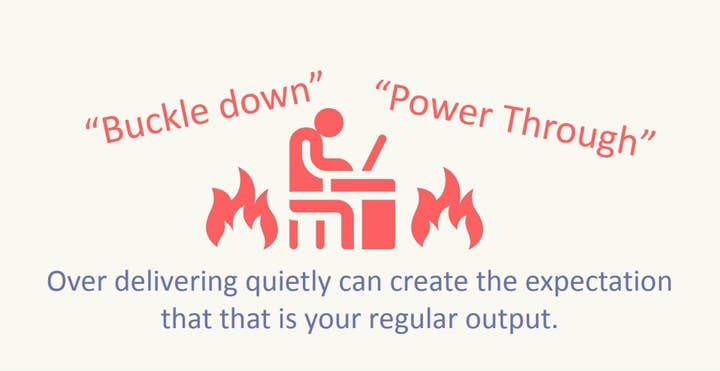

Fortier said one problem with this is that buckling down and doing excessive work without complaint can create an expectation that such output is the norm for you, so make sure people understand when the amount of work you're given is a stretch.

Nuance: Learning your limits, how to ask for help, and when to say 'no' are all important skills.

Fortier was specific about saying 'no' being a skill, something that has to be developed over time because it doesn't come naturally to everybody.

"The goal is to learn to advocate for yourself," she said. "And it will take practice, so practice it. But just as Dr. [Boccamazzo] said, you don't have full control, and this can be really hard to do if you don't have the support of the leadership around you."

If you don't have that support, Fortier emphasized that it doesn't reflect on your worth or your skill so much as it reflects on bad decisions of leadership.

Pressure: Everyone else is fine. I am overreacting and just need to work harder.

Nuance: I need to listen to my own emotions. They are valid and important.

"We can't know what other people have going on and how they present may not be how they are inside," Fortier said.

She added that in listening to your emotions, it's important to reflect on whether there's something in you "something scary, something dark" that you're afraid to question because it might unravel other parts of your life. That can be a long and complicated process, but even if you're not ready to go through that at any given moment, she said it's important to at least acknowledge it's there.

Pressure: If I don't finish this, I won't be a team player and I will have failed.

Nuance: I am allowed to leave.

"You don't owe it to anyone to burn yourself down into a nub of your creative self," Fortier said. "Take a step back from deliverables, expectations, promises and deadlines, and ask yourself the real hard question: Is where I am helping or hurting me?"

She added that "passion" is a common thing in this industry, and that it can work against people just as easily as for them. And even in the midst of burnout, it's a difficult thing to ignore.

"It's very hard not to care," Fortier said. "So many times I found myself saying, 'I just don't care anymore.' I was lying, I always cared. And I think that's beautiful, and precious, and it needs to be protected. So as long as we're working in the systems that we're working, I hope you all show yourselves the same care that you put into your work."

Suffering in silence

Osama Dorias has been a public figure in games for a while now. In addition to his design roles at companies like Gameloft, Ubisoft, Minority Media, and WB Games Montreal, he also teaches game design at Dawson College, organizes the Montreal Independent Games Awards, co-hosts The Habibis podcast, and co-led the IGDA Muslim in Games special interest group.

As he detailed in his presentation, he also grappled with occupational burnout.

"I'm sharing my story because I hope it can help people know what burnout can look like," Dorias said.

"I would tell them, 'I had a burn out," and the answer was usually, 'So did I.' And we just do it alone, quietly."Osama Dorias

Many of the people he worked with were unaware he was struggling until he told them, just as he was unaware they would be able to relate.

"I've spoken to so many people," he said. "I would tell them, 'I had a burn out," and the answer was usually, 'So did I.' And we just do it alone, quietly."

While Dorias has long been busy in the public eye, he traced his difficulties with burnout back to 2019, when his mom was diagnosed with breast cancer and schedules had to be rearranged as he scaled back his work week to help care for her. But just as she went into remission, the pandemic hit.

"As an extreme extrovert, I mean really off-the-charts extrovert, it was extremely difficult for me to stop all the things that gave me joy and energy," Dorias said.

That meant no teaching, no going to the gym, no event organizing, no public speaking, not even social calls unless Dorias felt he was drowning.

He lived in a three-bedroom apartment that had seemed spacious before, but lockdown quickly changed that as he worked from his bedroom, the thin door doing little to keep out the increasingly common sounds of fighting children as everyone found themselves cooped up in tight quarters for long stretches of time.

Dorias said he spent almost every hour of the day in the bedroom, going from sleep to work and only leaving it to get food or watch a couple hours of TV in the evening.

"I developed insomnia as a result," Dorias said. "I couldn't sleep. I'd walk into the room and all I could think about was work."

Many nights he would only get an hour or two of sleep, if that, spending the rest of the night staring at the wall and trying not to look over at the computer where he worked.

"I no longer got any joy from any of the activities I used to get joy from before," Dorias said. "I didn't even enjoy playing video games, watching movies, reading books or anything. All those felt like a chore. 'Ah, I need to disconnect from work. I've got to do something else. I've got to do this.' And that felt like work to."

"I never thought ahead. It was always survive the day, survive the hour, survive the minute, survive this task..."Osama Dorias

He fell into a depression, suffered from migraines, and experienced intense bouts of fatigue and sudden panic attacks. By this point he had begun to teach and speak remotely and provide some mentoring, but he cut back on those as well.

"I never thought ahead," Dorias said. "It was always survive the day, survive the hour, survive the minute, survive this task, whatever I had to do. And every day got harder than the day before. I had less and less energy, cared less and less about anything, and couldn't focus."

Dorias also started getting angry for no reason, which he described as very out of character. The attitude change also impacted his work life, where his normal optimism and positivity was replaced by cynicism and pessimism that made it harder to function.

"I took longer and longer breaks where I would just be present, but not really there. Eventually I started taking days and weeks off at a time."

Then one day, Dorias said he felt better. He had energy and drive, and was tremendously productive for a week. He wasn't actually better though, as he discovered the week after when he couldn't get out of bed for several days straight.

"It turns out that it's normal to get a burst of energy before collapsing," Dorias said. "It's not unlike the thrashing throes of someone who's drowning before they get submerged and aren't able to move any more."

He finally talked to his bosses about what he'd been experiencing and they made him go see a doctor, who immediately put him on sick leave.

The recovery process wasn't easy, but it soon started to show progress. He started taking walks, and saw a personal trainer and a physiotherapist. He started going to therapy, tried out hobbies, cooked for the fun of it, biked, and took an assortment of medication to help with the panic attacks, the sleeping problems, and blood pressure.

"You don't know how bad things are until you feel them good again for just a little bit, then you realize how helpful it is," Dorias said.

He moved the family out of the apartment and to a house with a separate office, which helped him disengage from work and gave the kids their own room, which cut down on the fighting.

But even with all those steps forward, he was still mostly unhappy apart from short bursts.

"I misrepresented my situation to the doctor and I went back to work too early. It was the stupidest thing I've ever done."Osama Dorias

"The reality is I associated my self-worth to productivity and I wasn't being productive," Dorias said. "I was useless, and therefore I was worthless. So I misrepresented my situation to the doctor and I went back to work too early. It was the stupidest thing I've ever done."

The first week back went well enough, but after that Dorias realized he'd made a mistake. He stepped down as a lead at the studio and still couldn't keep up with the workload. That was when he started talking with his industry friends about the situation and learned how many of them had their own experiences with burnout.

He switched gears, taking three months of vacation he had accrued (an option that he notes in hindsight was a red flag). Even with that time off, he found himself unable to do anything creative or problem solve the way he used to. So he left his job and took a "senior partner relations manager" role with Unity, being upfront with them about his burnout in the interview and finding them welcoming regardless.

Dorias worked at Unity for nine months, and over that time his creativity started to return and he realized he had started healing. Eager to return to design work, Dorias took a job with Blizzard Entertainment last October, again informing them of what he had been through during the interview process.

"I had to set expectations because I used to be an overachiever and now I'm just an achiever? So I'm trying to be kind to myself, but I still have relapses," Dorias said. "I have days where I wake up and I can't do it. Thankfully now it's more like hours that I can't do it. It's getting better.

"And when my brain is firing on all cylinders, I'm the old Osama again. I design three things in one day and I finish them and they're great, so I still have whoever I was there in me, somewhere."

"I'm extremely grateful to everyone who helped me through the hardest parts. I love you all, and many of you are here. And I hope my story helps people struggling with creative burnout to learn the warning signs, and to know that we're not alone."

Utmattningssyndrom

Like Dorias, Anna Brandberg found her experience with occupational burnout brought on partly due to the pandemic.

"I moved across the world to Stockholm for a new job just before the pandemic broke out, and I quickly found myself isolated in a foreign city," Brandberg said. "Everything shut down around me and work was all I had left, so I threw myself into it.

Brandberg said she was running at 120% from Monday to Friday, but couldn't get out of bed on the weekends.

"And then I'd beat myself up for being so unproductive, and I would go back to pushing myself to extremes again," she said.

That pace had her unable to unwind at night and dealing with anxiety and insomnia that became intense enough she got a prescription for sleeping pills.

"I'd be washing the dishes and suddenly I would just disintegrate into a puddle of tears on the floor, sobbing until I couldn't breathe, and I didn't understand why."Anna Brandberg

"I was having daily panic attacks and breakdowns," she said. "I'd be washing the dishes and suddenly I would just disintegrate into a puddle of tears on the floor, sobbing until I couldn't breathe, and I didn't understand why."

She forgot about meals, had "dramatically scary" weight loss, and noticed her hair falling out.

"It was when the brain fog took over that I got real scared," she said. "I had entire days where I would lose hours of my life. I'd finish meetings and have literally no idea what [anyone] said, not even me. I'd be mid-sentence and suddenly I would just lose the entirety of the English language. I realized I couldn't trust my brain at all."

There was work to do though, and she felt guilty for taking any kind of a break as a result. Brandberg says she also suffers from clinical perfectionism, so anything less than perfect felt like failure to her.

"It got to the point where I actually asked people to stop asking me if I was ok because every time they did, I would just start crying," Brandberg said. "And I didn't want to let them know I was falling apart."

She tried to keep up the façade that she was doing fine because she had always seen herself as a strong person, the one other people go to for help.

"The first step was realizing I was in fact not ok," Brandberg said. "I had to admit that I was drowning, and I needed help. And I learned that help was available as soon as I asked for it."

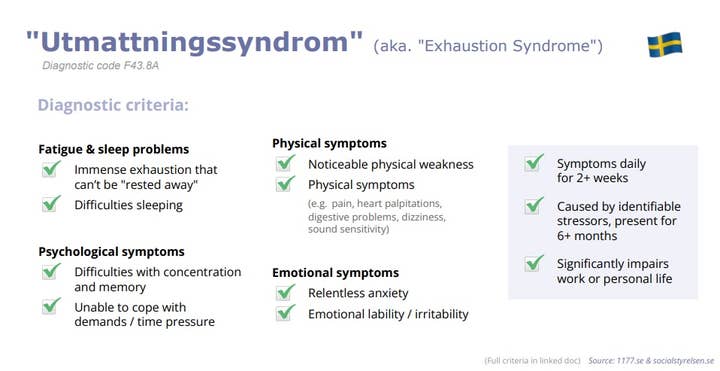

She said Sweden is one of nine countries in the world where occupational burnout is an actual medical diagnosis – Utmattningssyndrom is the clinical term – and the public healthcare system made sure she could get doctor appointments, stress rehab, and everything she needed without paying out-of-pocket.

She was assigned a case worker who met with her employer to ensure that her workload would be adjusted to enable recovery in a sustainable way. They told her to take it slow and mentioned how returning to work too soon could be harmful, but Brandberg wouldn't hear of it, explaining, "I wanted to be the best rehabber ever, and I wanted to go back to work as soon as possible!"

The doctor wanted her to take off work entirely right away, but she insisted on working part-time.

"The doctor wanted to put me on 100% sick leave straight away, but I refused, because of course I did," Brandberg said. "I insisted on still working part-time for two months before I realized I couldn't do it any more. And after that, I was completely out of commission for two months before coming back to working 25% while I attended stress rehab on the side."

After that, Brandberg carefully moved to working 50% of her usual working hours before she finally returned to full-time work. All told, the process took nine months.

"I wish that I had listened," Brandberg said. "I wish I had taken time off straight away. Perhaps I would have avoided the crisis phase all together. And I wish I would have allowed myself a gentler return back to work."

Just because she's back to work doesn't mean she's fully recovered. Brandberg says the recovery phase from occupational burnout can last for years, with lingering symptoms and a pronounced intolerance for stress.

"This is something that I am still struggling with today, several years later," she said. "I can no longer handle the amounts of stress I used to. I fall apart way faster than I used to, and it's so frustrating, because I should be able to handle this, and I can't."

She also emphasized that recovery isn't a smooth upwards curve, that setbacks will happen, and it's important to accept them as part of the recovery process, understanding what caused them and what their effects were.

"I am still in burnout recovery two years later," she said. "Recovery generally takes years, but you can make huge changes within just a few weeks."

"Burnout is a systemic failing, not an individual one. It is your workplace that has failed you, not the other way around"Anna Brandberg

She offered some suggestions for people approaching or experiencing burnout.

"First and foremost, remember that burnout is a systemic failing, not an individual one," she said. "It is your workplace that has failed you, not the other way around."

She suggested talking to the person responsible for your workload and asking them to help put a plan together. And if returning from a burnout-induced absence, make sure the workload and responsibilities are adjusted to avoid putting you back into a state of crisis.

"It's not on you to adjust to your workplace," she said. "It's on your workplace to adjust to you. And if your workplace isn't willing to help you with a recovery plan, consider whether you should even stay in your current job or not. And I'm aware this is said from a position of privilege, but is your job worth risking your entire health for?"

For managers, she noted it is faster and easier to help a current employee recover than to find, hire, and train up a replacement.

Beyond that, she advised people to revisit expectations about what needs to be done, what can be done less-than-perfect, and what things can be outsourced entirely. It's also important to identify a support network of people around you, both in the workplace and out of it, who can help in getting through difficult times.

"You'd be surprised at how many people would be more than helpful to help offload simple things for you," she said, adding, "Write down two or three people who can drag you out kicking and screaming for your stupid little walks for your stupid little mental health."

Finally, Brandberg noted that overworking is a very fast way to have a very short career, and asked people to keep the job in perspective.

"We work in video games," she said. "It's easy to forget, but nobody will actually die if your video game is slightly worse than it could have been in a perfect world. No game, company, or project is worth your health."

If you want to watch the entire presentation, it is one of a number of selected talks available for free on the GDC Vault.