Escaping the Asylum: Rocksteady's five designs to success

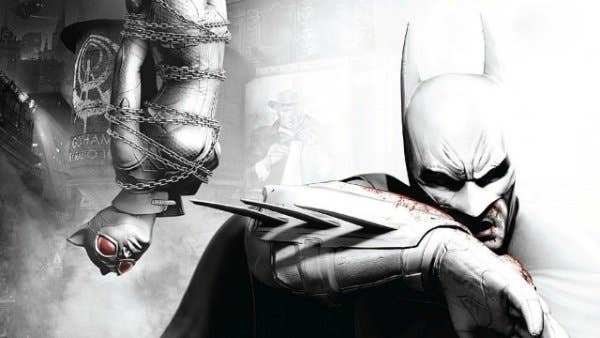

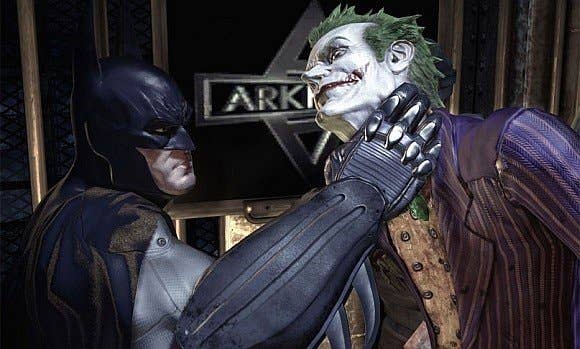

Sefton Hill details the studio's approach to creating two celebrated Batman titles

At the 2012 DICE Summit last week, Sefton Hill, co-founder of UK studio Rocksteady Games, detailed his approach to creating its last two hit games, Batman: Arkham Asylum and Batman: Arkham City. Here are the five key points that helped create the most celebrated licensed properties of this console generation.

5. Rapid prototyping.

All prototyping at Rocksteady is done in-game. When the team comes up with an idea they want to implement, they get it in the game as quickly as possible. Gameplay needs to be iterated quickly, said Hill and it can either be improved or killed if it doesn't work. If you can't iterate quickly you'll have less ideas. Ideas have an energy or momentum that keeps the team motivated and excited, and that helps get the team through the tough times - the doubt and problems that crop up in game development. If your iterative process is slowed down you lose that buzz that enables successful problem solving, said Hill. He also advocated taking more risks, because risks lead to standout features that help your game be more distinctive. Ultimately, aim to shorted the gap between ideas and implementation.

4. Smart foundations.

When deciding on the rules of the game world, make sure they are fun and fair. Batman: Arkham Asylum was about creating an island that was linked by small areas and rooms, which meant Rocksteady never had a large problem with the world, just smaller more manageable problems. That restriction also helped make the game better because it enabled the team to focus on single rooms in the game and ask 'how good is this room?' With Arkham City the studio joked that it wanted to make the world's smallest open-world game. While competing games were going bigger, Rocksteady wanted to work smaller. Puzzle gameplay that was taken out of Arkham Asylum was put back into Arkham City and justified by using The Riddler, a villain that wants to out-smart the hero. Making games "is bloody hard" said Hill, so create you own rules and justify your features through setting. There's a reason why Portal is set in a testing lab and Mario lives in a mushroom kingdom.

3. Constant re-evaluation.

Game features accelerate at different rates, and all games have stand out features and weaker ones. If you spend too much time trying to improve the weaker ones, your stand out features will only be 8 out of 10 features. So instead of trying to improve the weaker features, drop them, and concentrate on making the standouts truly stand out because they are the elements that will get your game noticed. If possible, combine weak features that you can't drop into one bigger feature. Decide what you want to beat your competitors at and focus on them, and remember that features you don't put in the game can be just as important as those you do put in.

If you're trying to second guess what the player wants, you'll end up making sycophantic design decisions to impress the audience.

2. Psychic powers.

How do you second guess your audience? In design meetings if you're trying to second guess what the player wants, you'll end up making sycophantic design decisions to impress the audience, and those features are only good for the game box, they're not right for the game. If you try to second guess you'll make safe game choices, and become paralysed by second guessing. Games designers know best, said Hill. You work in a office stuffed full of people who want to buy these games. You are your own market research, so ask what excites you? Make the game you want to play and your team will become passionate, and that passion will translate into gameplay. The only caveat, said Hill, was that you have to put yourself outside the game, imagine the game you want to play but be ignorant of the game you're making.

1. The Arkham recipe.

Never forget the key goals that drive the core mechanics of the gameplay. Hill said that when he plays a new game for the first time he often gets his arse kicked. But remember that games are there for the player's entertainment, the player shouldn't have to earn the right to play them. Try to make early stages fun, easily. In the Arkham games Rocksteady starts with the free flow combat that feels instantly rewarding and empowering to the player. Then once the player is drawn in, the game introduces deeper mechanics and harder enemies that require different tactics, so the game keeps challenging the player. Rocksteady then brings in complementary design such as the Predator gameplay, Riddler gameplay, story gameplay, navigational gameplay, all which help to give the action context. Then combat is also a release from the tension of the other gameplay. Hill also said that authenticity is central to the game, and with the Batman character it was important not to get sidetracked by non-authentic ideas. The restraints of the character define him, the fact Batman doesn't kill needs to be explained. Because Batman doesn't use a gun, Rocksteady didn't have to fall back on clichéd gunplay design. Instead they could celebrate and explore the limitations of the character. This isn't just something that comes from a licensed character like Batman, said Hill, and is more important if you're creating your own character - you have more creativity to create something unique.