Drinkbox cuts through the noise

Severed studio founders reflect on eight years in business, mid-gen console upgrades, the already crowded VR market, and the problem of relying on popularity to solve discoverability

A little over eight years ago, Pseudo Interactive was imploding. The developer of the Full Auto series of games had been working on a new game in an existing IP, but the publisher had pulled the plug. Unable to find a new project, Pseudo Interactive laid off most of the staff, and even those who remained knew it wasn't long for the world.

"We kind of saw the writing on the wall and started meeting with each other, asking what we were going to do next," former Pseudo Interactive developer Graham Smith told GamesIndustry.biz this week. "A few of us didn't want to leave Toronto, so we started discussing the idea of trying our own thing. At first that group was pretty large, but it slowly got smaller and smaller."

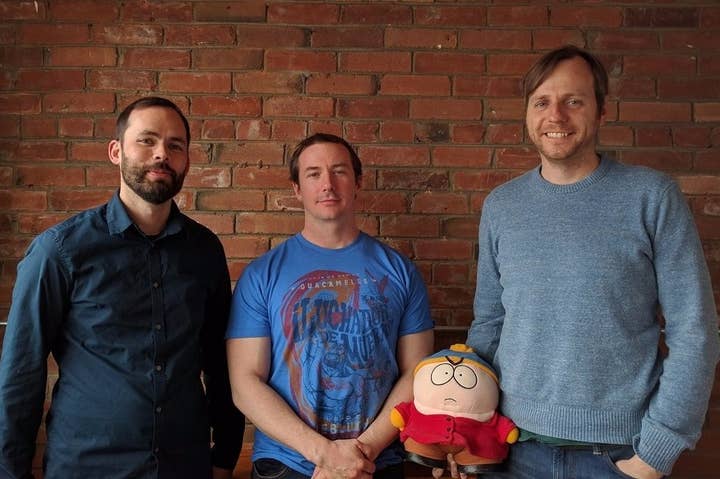

In the end, only three people remained committed to the idea: Smith, Ryan MacLean, and Chris Harvey, all of them programmers. Inspired by fellow Toronto developers Jonathan Mak (Everyday Shooter, Sound Shapes) and Metanet (N+, N++) to make a go of it on their own, the trio co-founded Drinkbox Studios. That was eight years ago this month. In that time, the studio has released four games based on its own intellectual property (five if you want to count the Super Turbo Championship Edition of Guacamelee!), the last of which, Severed, launched on the PlayStation Vita this week.

"It feels like the Vita market--at least from the perspective of Vita supporters--they feel under-served. So there is this kind of hole that hopefully Severed will fill a bit."

Graham Smith

But the Drinkbox story didn't start like that. Initially, the three developers shopped their programming skills around, doing contract work to build up a bankroll. They worked on the multiplayer networking code for Activision's Marvel: Ultimate Alliance, as well as a field goal kicking interactive exhibit for the New England Patriots. They even saw a silver lining on the dark cloud that was their former employer's demise.

"When Pseudo Interactive went down, a lot of employees scattered to all over the world," Smith said. "We found ourselves having contacts at a lot of different companies, and when they had extra work they needed to outsource, they'd call us up and ask if we had any bandwidth to pick up the work."

Before long, they'd built up enough money to pay a small staff to start working on its first original game, Tales From Space: About a Blob, and begin applying for government applications. MacLean said it was the hardest stretch the studio's been through having to juggle starting on so many different tasks at once. But as the company's games became more successful, Drinkbox was able to switch away from contract work entirely and devote its focus to original projects, which MacLean said made for considerably easier sledding.

"That's not to say the market isn't shifting," he said. "You do have to stay on top of what's happening and try to plan around how things appear to be moving in the market and when you're releasing the game."

That might sound odd coming from a developer releasing a game exclusively for the moribund Vita in 2016, but Smith still sees an opportunity to succeed on the system.

"It feels like the Vita market--at least from the perspective of Vita supporters--they feel under-served," Smith said. "So there is this kind of hole that hopefully Severed will fill a bit."

It doesn't hurt that Drinkbox has a strong relationship with Sony (all of its titles have debuted on PlayStation platforms), and Severed's combination of touch-screen based gameplay and use of the d-pad makes it somewhat less suited for a traditional console or even a mobile device.

"There's kind of a reset on the storefront [with new hardware], so if you can put out games there early, there's an opportunity there to get a lot more eyeballs"

Chris Harvey

"Now we're going to find out soon how well it does on the platform, and we're pretty nervous about that because it's been a few years since we've released anything there," Smith said. "We're not positive it's going to sell as well as we hope, but that remains to be seen."

For the future, Smith said Drinkbox is probably going to make its living on the latest generation of consoles.

"The console market has done really well for us, and we're seeing the PC market is getting more and more crowded," Smith said. "The Steam marketplace has been changing quite a bit over the last couple years. There's tons of new games coming out every day, and it's harder and harder for people to stand out in that market. Just from the standpoint of being able to stand out or get eyeballs on your product, it seems like the console space is where it makes the most sense for us to focus our efforts."

And if that latest generation of consoles is an incremental upgrade--such as a hypothetical PS4K or Xbox One.5--Harvey said it doesn't make too much difference.

"For a big developer, they might not necessarily be overjoyed about it because of additional work that may have to go in to support different hardware SKUs, but as an indie developer, it's not really that big a deal," Harvey said. "Our games are not exactly pushing the edge of the devices anyway. So from our perspective, there might be some additional certification stuff to make sure it works, but it's not going to fundamentally change how we develop our games for the consoles."

But even if Drinkbox's work doesn't demand a new hardware generation every few years, Harvey's still happy to see it. You can always use more power, he said, but the benefits don't end there.

"There's kind of a reset on the storefront, so if you can put out games there early, there's an opportunity there to get a lot more eyeballs," Harvey said. "And that's part of the reason we shipped Mutant Blobs Attack as a launch title on the PS Vita. We knew from experience. Pseudo Interactive had done a couple of games that were basically launch titles, and we knew from talking to people internally that they always viewed that as a very positive opportunity. As developers, there's no objection to more power. And from a business standpoint, if we can get in there early, we'd see a big benefit to that hardware reset happening every few years."

However, that affinity for being there at launch wasn't enough to get the studio into VR. For one thing, Smith said the company's primary focus on 2D games doesn't really lend itself to the tech. But on top of that, he added that the VR market "already feels a bit crowded to me."

"VR was kind of a different scenario because Oculus was sending out developer kits for ages, and they had a lot of people making stuff for VR for a long time," Smith said. "So on launch day, it felt like people had a really long time to work with these kits and the barrier to entry was quite low. It feels pretty different from the way the console launches happen. That feels more like an exclusive thing, where you're invited to be part of a new generation of consoles, or you beg them to be part of it. It's harder to get in; it's more of a curated thing to me."

Harvey acknowledged that it's in any developer's self-interest for the barriers to entry on a platform to be set just beneath their ability to clear them, but even so, he's concerned about how far barriers to entry have come down in recent years.

"Speaking personally, I feel like the trend is going too low right now," Harvey said. "I say that because as a user, I'm finding it increasingly difficult to identify what I want to buy without having to rely on other people--or just the herd--to direct me to it."

"I feel like the [barrier to entry] trend is going too low right now... as a user, I'm finding it increasingly difficult to identify what I want to buy without having to rely on other people--or just the herd--to direct me to it."

Chris Harvey

Best-selling charts and recommendation algorithms may help people find more content suited to their tastes, but Harvey said some researchers have identified drawbacks to such discoverability solutions.

"When it's difficult to get information about the quality of a product that's reliable, you tend to rely on what other buyers have already chosen," Harvey said. "But when you rely on that, what tends to happen is a few things at the beginning--because of who randomly liked those things--start to gain in popularity and reach a critical mass where they take off enormously. And the more things you have on a service, the more disconnected quality is from popularity. That doesn't mean that what's popular will be the worst thing--something really terrible won't become incredibly successful--but it's increasingly likely something that isn't the best thing will become the most popular thing.

"So I'm a bit wary of things that are based on what other people are buying, how many other people bought this product. When there's a smaller number of things to choose from, the effect of choosing based on popularity isn't as negative. But as the barrier to entry goes down, and there's not enough time for review sites to take a serious look at everything, or for me as a user to try demos for the things that interest me, the relationship between popularity and quality will naturally decrease."

He added, "From a user's perspective, the problem is when the bar gets too low, you can't really make informed decisions and you're kind of forced to go with whatever the crowd thinks is good. It's difficult to make independent decisions, and as a result, you see games going feast or famine. A small number of games make enormous amounts of money, and most of the games make virtually none. And that's not really a healthy place for developers making a game, because the risk suddenly multiplies drastically."