Double Fine's new adventure: Publishing

"We don't get any of their Kickstarter money. We don't take a chunk of their funding" - Tim Schafer

There was a time, not so very long ago, when things didn't seem quite so rosy for Double Fine. Started by the inimitable Tim Schafer and a group of his LucasArts colleagues in July 2000, there was never any doubt about the talent behind the studio. But for a long time it was unclear whether Double Fine would ever find its proper place.

Psychonauts, its debut, was widely praised by critics on its release in 2005, but largely ignored by the public. Brutal Legend followed, but it became the subject of a protracted legal dispute with Activision, which had dropped the game after its merger with Vivendi. An out-of-court settlement prevented what seemed to be an inevitable defeat for Activision, leaving the way clear for EA to help publish the game in 2009. But it was a bittersweet triumph, as Brutal Legend's reception mimicked the same pattern as Psychonauts: lauded by critics, overlooked by the public.

"Maybe the old publishing model was just hard for me, because I'm someone who doesn't like to be told what to do"

By the time the dust had settled on Brutal Legend, Double Fine was nearly ten years old, and it's future seemed as uncertain as at any time in its history. What has happened since is one of the more remarkable turnarounds this industry has seen; an early example of what an industrious studio with a solid fanbase and a strong creative identity could achieve in the new landscape of digital distribution and instant communication.

When I meet Schafer at Gamelab in Barcelona, he admits that Double Fine's journey is, "a very unusual story," but it has left the studio where, in retrospect, it always needed to be: a faster turnover of smaller games, the owner of its IP, the master of its destiny. The last time Double Fine deferred all publishing duties on one of its games was The Cave, launched by Sega at the start of 2013. Looking forward, there isn't another such deal for what is likely to be two or three years of Double Fine releases.

"Maybe the old publishing model was just hard for me, because I'm someone who doesn't like to be told what to do," Schafer says. "That's maybe a bit childish, but that's the way I am. And I think that's the way a lot of indies are. They're independent. They don't like anybody acting like their parents, claiming they know what to do. [Publishers] aren't your parents. They're a business and you're a business, and when it comes down to it they're going to do what's right by them. That can be a dangerous thing for anyone just starting out.

"We wanted to share that and stop them from falling into that trap, because when you're just starting out you have such a great advantage over everyone else. You don't have a lot of bills to pay and employees to feed; you're just two people making a game and it's easy to be fooled by someone who comes along and says, 'You don't know what's going on. You're going to be taken advantage of by the industry, so comes to us, give us your rights, your copyrights, let us take care of you and make sure you're okay'."

"We want to step in and let them know they don't need anybody, just so they can stay independent"

Schafer recognises that most independent developers have a great many more options than Double Fine did when it was on the receiving end of that kind of attention. However, success in the games business is still far from straight forward, and publishers are remain keen to make the sort of deals that can leave an indie studio with little to show for a lot of hard work. This, Schafer believes, is where Double Fine can make a difference.

"We discovered that some of our history of being with AAA publishers and that kind of PR campaign, actually that experience had given us something that indies just starting out don't have," he says. "We want to step in and let them know they don't need anybody. We want to give as light a touch of help as we can, just so they can stay independent."

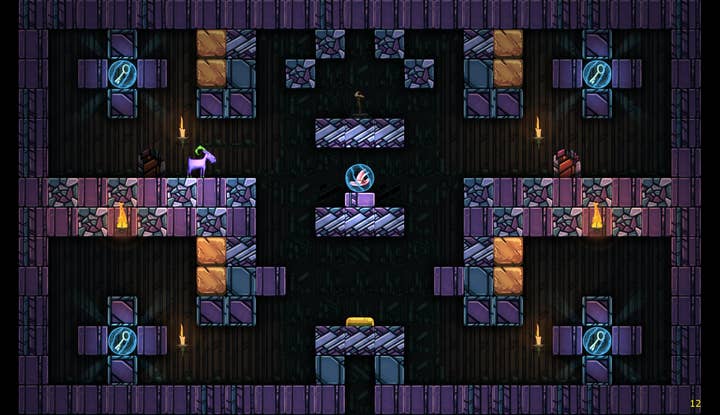

Double Fine won't be a publisher, exactly, but it will help a select group of developers with whatever they see to be their key problems. Schafer wants every game it helps to gel with Double Fine as an entity - it's unlikely to lend its support to a military FPS, for example, or a simulation racer - and he points to the two projects it is already working with as a perfect demonstration of what he means: MagicalTimeBean's Escape Goat 2 and Sam Farmer's Last Life, both creative and distinct, both with a very different set of needs.

"We're lending our notoriety and your experience to help out, but the main thing for us is it's customisable to whoever we meet," Schafer says. "Escape Goat 2 is done. We didn't help them make that game, but we can promote it. Last Light is just starting out, so we can help with their Kickstarter. Everybody will have different ways that they need help. Maybe they want playtesting and feedback from that, maybe they don't have any audio. We can be flexible and fit into whatever those needs are."

Which all sounds very altruistic, and Schafer appears to be sincere when he mentions that as Double Fine's sole motivation. But there's one inescapable fact: however well intentioned it may be, at its core this is a business initiative; one that will cost Double Fine time and resources, with an impact on the company's bottom line. Schafer is reluctant to discuss the specifics of what Double Fine will recoup from its partnerships, but he's under no illusion that it will have to be a two-way street.

"We're kind of just feeling it out right now," he admits. "If we want it to be something that's supported by a paid staff on hand to deal with it, we're going to need to be paid something. I think that would be something where, if a game is a huge hit, we'd be able to share in that in some way, but not have it be ticking a box upfront. We don't get any of their Kickstarter money. We don't take a chunk of their funding."

"If we want it to be something that's supported by a paid staff, we're going to need to be paid something"

Regardless of the help that Double Fine provides, the selective nature of the idea means that each developer will intrinsically receive something much more valuable: the studio's seal of approval, a tacit thumbs-up from one of the most influential indies in existence. Every so often, a relatively obscure horror movie may appear at your local cinema with "Guillermo Del Toro presents..." emblazoned above the title. Del Toro didn't make it, but he watched from the sidelines, dispensing sage advice where necessary and making damn sure that people knew it existed when it was finally ready for the public. Double Fine seems to be doing the same thing here, and Schafer welcomes the comparison with a grin.

At a time when the rising number of releases and the proliferation of free games, flash sales and bundle deals are sparking intense debate about the perceived value of the product, the blessing of a company like Double Fine is as good a way for an indie to justify a sensible price-point as any. As Schafer puts it, "maybe it could be priced in a way that would pay for the cost of making the game."

"After all these years of just talking non-stop we've got some notoriety, and what do you want to do with that?" Schafer asks. "You use it to help people out."

Tim Schafer's talk from Gamelab, which explores the intersection of games, art and creativity, can be seen below. We heartily recommend that you take a look.