Dimbulb or bright idea?

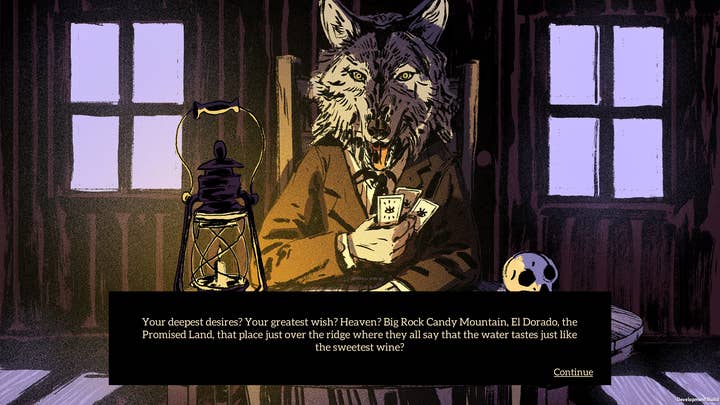

Fullbright co-founder Johnnemann Nordhagen explains why he left the Gone Home studio to go solo for Where the Water Tastes Like Wine

Johnnemann Nordhagen's career has a pretty well-defined trajectory. The designer of the upcoming American folk tale-inspired anthology Where the Water Tastes Like Wine got into games in 2003, joining Sony's QA department on a team testing networked PlayStation 2 games, then moving to the R&D department to work on the application team, including the PlayStation 3 tech teasers.

But as he told GamesIndustry.biz recently, "I got into the games industry to try and make games, not duck demoes and things like that." So when 2K Marin posted an opening for a platform programmer to help bring BioShock to the PS3, he figured it was a step closer toward that dream. When the studio began work on BioShock 2 and he shifted to be a gameplay programmer on the team, it was another.

"I wanted to get closer to making games, making them fun and interesting, having my ideas be there in game form."

During production on 2K Marin's next project, The Bureau: XCOM Declassified, Nordhagen realized there were better ways to pursue that particular goal.

"That was an unpleasant project for a number of reasons, for pretty much everyone there," he said. "After a couple years of that, I decided that I was unhappy with the project and not finding what I needed in AAA development. It was not letting me have as much creative impact as I wanted to, and the sorts of games I was interested in at the time were not the AAA stuff I was making. It was the indie stuff that was coming out."

So like so many other AAA devs of the era, Nordhagen went indie. He decamped for Portland with fellow 2K Marin expats Steve Gaynor and Karla Zimonja to launch Fullbright Games. Unlike so many of those AAA-devs-turned-indies, Fullbright's first project, Gone Home, was a critical and commercial hit for the company.

"That was a really cool experience," Nordhagen said of his time with Fullbright. "I'm super glad I was able to be the sole programmer on the project and take it from nothing to shipping basically all on my own as a programmer. However, I was still acting as a programmer, and while everyone on the team had some contributions to the project, of course at the end of the day it's Steve Gaynor's project. Gone Home was his baby. We all got input, but it maybe wasn't as much creative input as I was looking for.

"Anytime you make a game, it ends up being a collaboration and an effort among many different people... There are a ton of things I don't have the skills to do."

"After the game shipped and did well, I decided that was my absolute best chance to make something on my own, both from a financial standpoint and also from a visibility standpoint. The tough thing for indie games as everyone knows is to get recognized, and coming from a successful project is a good start for the news cycle. And then also because I had the experience of shipping a game from start to finish and I had the confidence I could do that again, it seemed like everything had come together for me to try and make my own project."

So like almost no other AAA devs of the era, Nordhagen left his very successful indie venture to go indie-er, starting the one-person studio Dimbulb Games. He went from working on the periphery of a platform holder operation with thousands of employees to a AAA studio with scores of developers to an indie studio of three to a studio that is literally just him. Still, he knew when he started he'd need help to realize his vision.

"Anytime you make a game, it ends up being a collaboration and an effort among many different people," Nordhagen said. "I'm a programmer, and I don't have any talent in art at all. I've done a little writing but I'm certainly not a professional. I can't compose music. There are a ton of things I don't have the skills to do."

But for a developer who spent a decade pursuing greater creative input, it might have been surprising that for his first project as a solo operation, Nordhagen has enlisted 16 other talented writers from in and around the games industry to help. That might sound like it has the potential to be a "too many cooks" situation, but the game's anthology format is letting Nordhagen tell a wealth of stories, each in a different writer's distinctive voice.

"When I started the game, I was thinking I was going to try writing it. That was always something I wanted to do. But I quickly realized that was not going to be feasible, both because I wasn't the right person to tell a lot of these stories but because I'm not a good enough writer to pull off something like this and make it as good as I want it to be.

"It turns out it was a really difficult job finding a vision, communicating a vision, and keeping everyone on the same page as well as being responsible for those decisions at the end of the day."

"But I still don't feel like I'm sacrificing any of the creative input I wanted. I still feel like this game is very much my baby. This is something I came up with the idea for, the feeling, and the all the rest. The writers are spectacular and have control over their own pieces of it, but I don't think that takes away from anything that I wanted out of the project. I'm incredibly lucky and glad the writers are doing their own thing because that's why I contracted these people."

That's where the ambition of Where the Water Tastes Like Wine resides. Nordhagen's a programmer by training, but admits all the problems the project presented from the outset were ones he already knew he could solve. And for the other disciplines, he was turning to more than capable professionals like his cadre of writers, concept artist Kellan Jett, and composer Ryan Ike. Still, just wrangling the contributions of all these people together into a single coherent project is a daunting task in itself.

"It was a lot harder than I initially thought it was going to be," Nordhagen said. "It turns out it was a really difficult job finding a vision, communicating a vision, and keeping everyone on the same page as well as being responsible for those decisions at the end of the day. At Fullbright there were three of us and while Steve drove the final vision, we all kind of signed off on it every time. I was really regretting a couple months in that I didn't have someone I could check ideas against, to at least get their approval on things to feel more confident about things myself. Trying to make decisions just on my own was incredibly daunting, especially about things I don't have a lot of experience with like music composition, artistic decisions, and even production stuff. I feel like I've learned more than I ever have before in such a short period of my life by trying to do this game and manage all this myself."

He added, "I was originally thinking it was not an ambitious game at all. When I started it, I thought it would be a pretty small scope game and I was aiming at a timeline similar to our Gone Home timeline, about a year and nine months in development. It grew into something much larger--or I just scoped badly at the beginning--but it's taken three years so far and it'll be a little while longer."

In an industry where trends move fast and timing is everything, that's a bit of a concern.

"Coming off of Gone Home, the idea of an experimental, innovative, single player narrative game seemed like a pretty good bet," Nordhagen said. "We had come out, people had loved it, there were very few of these games around, and it did very well. But you look now and it's like several of those games come out every day, a lot of them for free, and the ones that charge might sink like a stone. So that's terrifying.

"I think in general the indie game market has changed a ton. When Gone Home came out, there still weren't many indie games out there, so a lot of them got coverage. Streaming wasn't nearly as much as a thing, so you still just needed press and awards and things like that to sell your game. People were hungry for new, interesting experiences. It was a great time to be doing this. But now there are a ton of games like this, a ton of games in general, and a ton of really great games. And even the best of them often don't sell that well."

"I don't know how to make a game appealing for streamers. I don't even know if streamers are still the way to sell games now. That was a year ago and things seem to be changing every day."

Dimbulb has publishing agreements with Microsoft and Sony to bring the game to consoles at some point after its PC launch, but if it doesn't click on Steam, there might be little reason to think it would do better on the Xbox One or PlayStation 4.

"The console market has been changing a half step behind the PC market, I feel like," Nordhagen said. "There was a short time when releasing on Steam was still a dangerous proposition but releasing on console would get you into these free and open waters where there wasn't as much competition. That's obviously changing really quickly too, and now I don't think it's any better on console. They're making a lot of the same choices and aiming for a lot of the same things as the Steam market is, streamer friendly content and things like that. And as we could see from this past E3, it also seems like console makers as champions of indies have maybe backed away from that a little bit."

What's more, Nordhagen said he hasn't made many conscious adjustments to make the game more suitable to the market landscape it will eventually launch into. It has some elements that might be common among popular games--an open world, randomized events, different player paths, a distinctive art style--but Nordhagen said any overlap between the game and what works in the market is more or less coincidental.

"I don't know how to make a game appealing for streamers," Nordhagen said. "I don't even know if streamers are still the way to sell games now. That was a year ago and things seem to be changing every day. The only thing I can do now is hold on and ship the game I wanted to ship and see what happens with it. I'm not betting any farms on it having any commercial success, we'll say."

But like much of the oral tradition in American folk tales that inspired Where the Water Tastes Like Wine, the point for Nordhagen may be less about the outcome and more about recounting a well-worn story with his own personal spin.