Celebrity developers: What's in a name?

Bleszinski, Cage, Schafer, Romero, Chen, and Hecker on the pearls and perils of gaming fame

"'There's a tendency among the press to attribute the creation of a game to a single person,' says Warren Spector, creator of Thief and Deus Ex."--First sentence of a 2001 IGN story on Deus Ex: Invisible War.

A dozen years after that interview, we're in the midst of a golden age of celebrity developers. The big names in AAA development are starting their own studios, retaining intellectual property, or walking away on their own terms in ways they simply haven't before. At the same time, a new generation of indies are building names for themselves, collaborating with small groups to one-up their blockbuster counterparts not just in critical praise, but financial return on investment. Even celebrity developers of yesteryear are thriving, thanks to a seemingly unending parade of successful Kickstarter projects empowering them to revisit their roots in crowdfunded freedom.

But as Spector clearly understood and the IGN writer underscored, the boon of celebrity developerhood carries some baggage as well. GamesIndustry International recently spoke with prominent developers from different corners of the industry and asked them to reflect on the best and worst of their positions as recognizable development heads.

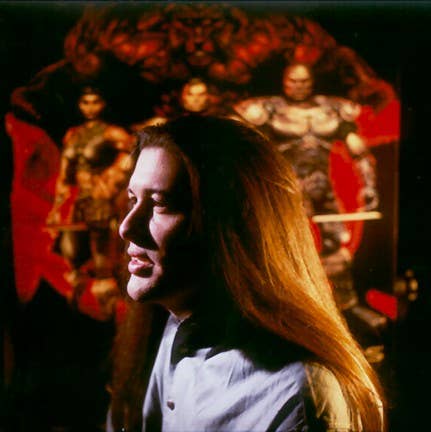

"It's a good thing and a bad thing," said Quantic Dream's David Cage. "It's a good thing in that sometimes it makes things easier for people to get a face on a game or a studio and to notice you have a voice and to express what you think, how you feel, and why you do things. It's generally very positive in that sense."

On the other hand, the director of Heavy Rain and the upcoming Beyond: Two Souls said that when people disagree with what he says or how he says it, things get personal in a hurry.

"So they don't see the game, they don't see the company. They just see your face and they don't like what you say, and 'F***, I don't like your games.' And that's exhausting. That's exhausting."

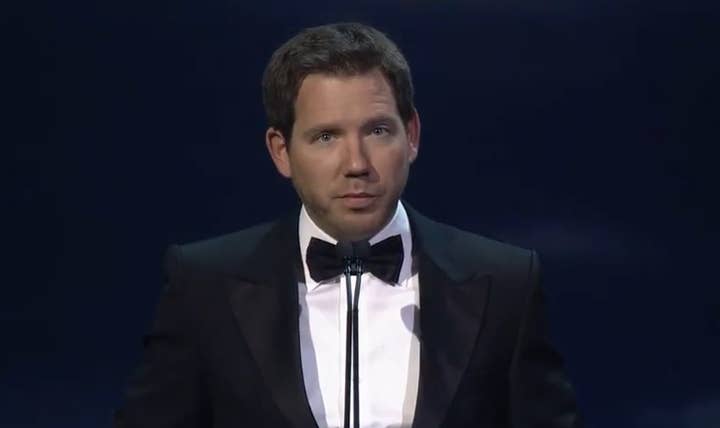

Former Epic Games design director Cliff Bleszinski has experience with that. In his 20 years at Epic, the developer made a name for himself with the Unreal Tournament and Gears of War series, the latter of which was tremendously successful while being simultaneously mocked as the standard-bearer of "dudebro" AAA games. For Bleszinski, the two traits are likely linked.

"I remember seeing Romero being a rock star and me as a young developer, going, 'F*** that guy. Who does he think he is?'"

Cliff Bleszinski

"Everybody loves to watch somebody make it big, but everybody also loves to watch somebody fall," Bleszinski said. "Sometimes I'm confounded by it, but if I travel back in time and think about my personal experience, I remember seeing an ad for Tommy Tallarico's [Virgin Games Greatest Hits Volume One music CD] in Electronic Gaming Monthly. And I'm seeing this guy wearing ripped jeans and sunglasses, with the acid-wash, and I'm just like, 'Who is this douchebag? Why is he so cool?' And I remember the rise and fall and rise again of John Romero. And I remember seeing Romero being a rock star and me as a young developer, going, 'F*** that guy. Who does he think he is?' There's something there in regards to insecurity where with somebody who's successful, it's immediately fun to just dislike that person."

Even being on the receiving end of that hate has a certain allure, Bleszinski said. "It's one of the things that being a visible developer, you kind of get past being upset at people hating you. But you actually still are fascinated by it, which is such a weird dynamic. You'd rather have them say something bad than ignore you, because ignoring you is actually worse."

As for Romero himself, the co-founder of Loot Drop and veteran of seminal first-person shooters like Doom and Wolfenstein 3D said it was just realistic that the person most associated with a project in the public eye take the blame if it ultimately disappoints. Romero's personal stock took a hit when the heavily hyped Daikatana launched to negative reviews, and while he notes misgivings with that title's marketing campaign, he fully understands why the blowback from players was aimed at him.

"If you market heavily and the game doesn't live up to it, then you're going to get slammed heavily," Romero said. "But if you're a developer that has a name like Sid Meier or Will Wright and you come out with a game that's not great, it's tough. It's something we call the Pavarotti Effect. Every time you put a game out, it's got to be the best, or better than the last one. Everyone expects you to be Pavarotti every day, but it's really hard to be Pavarotti. You can't really mess up."

At the same time, Romero doesn't see a problem with the name behind the game being lauded when things go well.

"The person who's in charge is one of the biggest reasons why it's going to go well or not," Romero said. "A lot of times the person in charge is the one hiring the people to be on the team as well. So it's even more difficult. It's not like those people were just sitting there, and then were scooped up and thrown on a game. A lot of times they hand-picked the people through a laborious interview process to create the team. And that's a big deal. It's a lot of effort to do that. And that's not anything that anybody thinks about when they see a finished game, the insanity of the workplace or dealing with [human resources]."

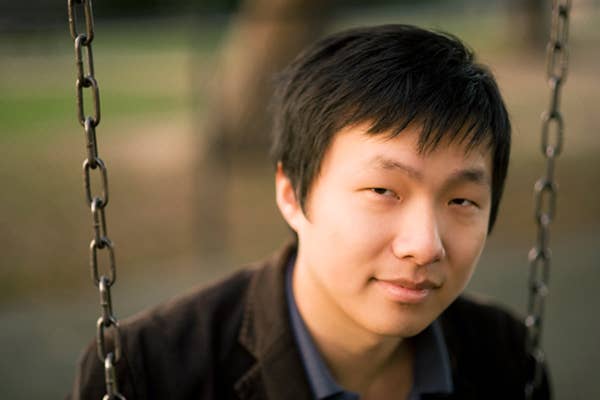

As a development celebrity whose career arc still seems in its relative infancy, ThatGameCompany's Jenova Chen hasn't been as much of a lightning rod for negativity just yet. Even with that lack of backlash and a flood of adulation for last year's Journey, Chen's view of gaming celebrity still isn't especially positive. When asked about the benefits of game fame he's experienced to date, Chen simply said it was nice being able to start a conversation with someone in the industry and finding them already familiar with his work. But as far as benefits beyond that?

"I don't think the name 'Jenova Chen' has any value at this point. Maybe in the future?"

Jenova Chen

"I think nothing, really," Chen said. "For me, I'm still doing my work every day. My life is no different from five or six years ago. I'm still working with the guys I've been working with on the games. Even for getting publishing deals or investment deals, it's not me who's getting the money. It's our games, the games we make. My name doesn't really bring me money. It's the game, it's the team, it's the brand. If it's not ThatGameCompany, my name by itself can't raise any of these things. I don't think the name 'Jenova Chen' has any value at this point. Maybe in the future?"

It seems a small leap to suggest Chen's point of view is informed by the recent past, when his name couldn't help ThatGameCompany avoid bankruptcy as it struggled to finish Journey. As for the downsides, the first subject Chen brought up was the demands his status made on his time.

"A lot of interviews which makes me not ever able to focus on the game," Chen noted during the interview. One would expect those qualms to be aggravated when the journalists for whom he has made time then turn around and sensationalize his comments for hits, as he said happened a few times in the past year.

But if Chen sees less of the upside than one might expect, he also takes a measured approach to its downsides.

"Initially I was very angry because I thought I was misrepresented," Chen said. "But later on, I was like, I guess that's not a bad thing, either. It's bad that they misrepresent you, but at least they care enough to misrepresent you. At least they think your name's going to make for big news."

Chris Hecker knows a thing or two about unexpectedly finding his quotes at the center of an Internet uproar. In 2007 while working on Spore, Hecker likened the Wii to two GameCubes duct-taped together and called it "a piece of s***" during a Game Developers Conference rant session, prompting the usual Internet firestorm. Hecker apologized in another GDC session the following day, but those sentiments would provide headline fodder whenever his name came up years down the road.

While Hecker is now known primarily for his upcoming indie game SpyParty, he was by no means the biggest name on Spore. That would have been Will Wright, celebrated creator of enduringly successful games like SimCity and The Sims. But Spore was a massive project with hundreds of people in the credits, and morale may have been impacted by the overwhelming focus of the project locked on a single person.

"You gotta make sure that the team gets the credit for making the game because they're the ones putting it together."

John Romero

"On Spore, I sent out mail to the team, just kind of curious, and said, 'Hey who thinks Will's name should be on the front of the box versus not?' And the vast majority of people on the dev team said 'Not,'" Hecker said. "I was kind of blown away by that. I thought they'd want Will's name on the box."

Indeed, managing the morale of a team working hard while one person is given all the credit was a common concern among those interviewed. ThatGameCompany makes a point of nominating the entire development team for awards rather than singling out any individuals whenever possible, Chen noted. At the BAFTA awards this year (at which Journey led all games by winning five categories), Journey's Game of the Year nomination was credited to "The Development Team." (By contrast, fellow Game of the Year nominee Mass Effect 3 was credited solely to Casey Hudson.)

And even though Romero supports the buck ultimately stopping with the developer in charge, he was entirely mindful of how important the developers in the trenches are, sharing credit with them when it comes while sheltering them from blame.

"You gotta make sure that the team gets the credit for making the game because they're the ones putting it together," Romero said. "There's the lead who has the vision to make the thing, and then there's everybody making it. And the quality of 'making it' is critical. How it's done is critical. So when you're getting credit, you obviously have to give credit to the team for doing a great job. But usually when a game does bad, you don't go blaming the team so much. You were responsible for guiding the development of that thing, so why did it go so bad?"

Bleszinski said he always tried to balance his public role with giving proper credit to the team. Still, he espoused the notion of celebrity developers in the AAA space as "defiant visionaries," creative forces who ignore typical focus group concerns and fight through development obstacles in order to craft the experience they have in their minds. He noted BioShock Infinite's Ken Levine as a prime example of a defiant visionary who leads the charge for a game while properly managing credit for his team.

"As much as game development is an amazing, collaborative process, a team effort just like a sport is, you need the coach or the quarterback who's calling the shots at the end of the day," Bleszinski said. "You need your Steven Spielberg. You need your David Jaffe. You need the guy who's going into that boardroom and saying, 'Look I want to make a game about an underwater paradise gone wrong' or whatever to get those people to buy in. And if you don't have that, you wind up with oatmeal, as Mike Capps used to refer to it. Nobody really likes or hates it; it's just kind of ok, just kind of there. And that's what leads to a lot of generic intellectual properties, unfortunately."

"As much as game development is an amazing, collaborative process, a team effort just like a sport is, you need the coach or the quarterback who's calling the shots at the end of the day."

Cliff Bleszinski

On the other hand, Bleszinski dismissed one concern with the defiant visionary, the idea that a celebrity developer's reputation would be so impressive (or oppressive) to his or her team that people fear questioning them and potentially constructive feedback is lost.

"Game developers are some of the most smart people in the world, but they're also some of the most insecure," Bleszinski explained. "And the thing they're most insecure about is their intelligence, even though they're brilliant. So they see the need always to re-prove that intelligence."

He suggested pitching James Cameron's blockbuster film Avatar to an average developer and watching them tear the idea apart, from the ridiculously named "unobtainium" to the Smurf-like blue-hued forest-dwelling aliens. Developers would generally see all of the flaws in such an idea clearly, while glossing over the idea that execution makes the difference between such stories being hailed as brilliant or derided as absurd.

While Bleszinski is "semi-retired" for now, he is working with a handful of artists in preparation for a return to active development at some point in the future.

"I'm actually at the point where I'm dictating things and being very hands on, actually design directing and art directing on my own ideas, without being second guessed every step along the way," Bleszinski said. "That was one of the things that got very old in game development toward the end. No matter how successful you are, there's always somebody questioning you, second guessing all the time. And that kind of thing gets very old, very quick."

"If you believe in your idea, you have to sometimes have confidence and be willing to be seen as a monomaniacal narcissist."

Tim Schafer

While Double Fine Productions' Tim Schafer would never refer to himself as a defiant visionary (not with a straight face, at any rate), the founder of the Brutal Legend development house--and Battle of Lexington and Concord for the Kickstarter Revolution--confessed that he considers his celebrity from a very strategic perspective, and always has. Schafer said when he and fellow LucasArts developers Ron Gilbert and Dave Grossman landed their names on the boxes of their games, it was a "self-promotion coup" that helped them get a foot in the door when meeting with other publishers. And while Schafer doesn't need to try so hard to get such meetings these days, he isn't about to shy away from taking credit for a team's work so long as it was shaped to his ends.

"I guess I have a big enough ego to feel that that's totally appropriate," Schafer said. "If someone else was in charge of that game, it would have been a completely different game... A lot of people shy away from talking about auteurs and stuff because they think it feels really egotistical to say, 'This is MY vision' and all that stuff. But it's only egotistical if it doesn't work. It's only egotistical if you're doing it just for your own ego. If you believe in your idea, you have to sometimes have confidence and be willing to be seen as a monomaniacal narcissist. But that's what it takes to get these things made sometimes."

Schafer's approach to his development teams on such projects likewise reconciles a respect for his co-workers with a focus on realizing his vision.

"When I usually get the impetus to make a game like Psychonauts or Brutal Legend, it's like, I gotta get this game made so I gotta convince a bunch of people that this is a cool idea so they'll believe in it too. Then they don't feel like it's Tim's game. They feel like they believe in it and it's their game, it's our game and we're making it together...I could just imagine someone saying 'How narcissistic of you to think everyone should make your little heavy metal fantasy.' And I guess it is. But I think that's fine. If people didn't have egos, I think there wouldn't be any art."

So Schafer could be said to sport an ego, but to hear him tell it, it sounds like a means to a more selfless end.

"When a company grows to a certain point, you really want other people to be able to step forward and take their moment in the spotlight, like the leaders of our projects like Lee Petty, Nathan Martz, Drew Skillman and Brad Muir," Schafer said. "And it's also really good for the company to have all those people get their credit because it shows that the thing that is valuable isn't my name but Double Fine itself. My dream for Double Fine is that it's just a creative machine putting out great ideas every day. And that means it's a place that fosters creativity and individual personal expression."

That emphasis on individual personal expression is exactly why Hecker said he wanted Will Wright's name on the packaging for Spore.

"I want there to be not a star system just to be famous, but because I think that's healthy for creators creating. It's just really strange to me how even developers don't have an interest in this."

Chris Hecker

"I think that's aspirational for me. I want there to be not a star system just to be famous, but because I think that's healthy for creators creating," Hecker said. "It's just really strange to me how even developers don't have an interest in this. And I think a big explanation for that is that most games are so impersonal right now. The fact that Activision is able to rotate round-robin their biggest franchises between multiple developers basically proves the point that there's not a lot of personal voice in these games. They're software products that are allocated to teams. And I think that will change.

"Take The Witness, Jon [Blow]'s game. You're not giving The Witness 2 to somebody else and having a good game done that feels the same way. It's Jon's game. It's about Jon's life. And I think the same thing will be true of Spy Party. The same thing is true of Journey, Bastion, all of these indie games that are very personal. I think those things are all tied together: the personal-ness, the artistic statement of games, whether your game is something you're trying to say and share with the world versus you're just trying to do this cool thing that will sell a lot of copies.' Indies will do it no matter what, but I think the companies might have to start doing that too. They're going to have to start cultivating these people and giving them voice, letting them take slightly risky things and not shaving all the rough edges off a personal voice."

More auteurs will likely mean more criticism from the masses. Should that be the case, the next wave of celebrity developers might do will to adopt the attitude of Romero, whose wife refers to him as "The Teflon King" for the way he lets anonymous, unconstructive criticism slide off him. Despite whatever drawbacks the spotlight may have, Romero said the position is one of privilege, and absolutely worth the headaches it may bring.

"It's not even a comparison," Romero said. "It's great. It's super great. If you screw it up, then you take it. If you do great, then awesome, keep doing great stuff and people love it. When you have a really long career, you're going to have failures. Some of them might be really bad ones. Some of them might be public, some might not be so public. But that's all part of having a long career. Having a short career? Not as exciting."