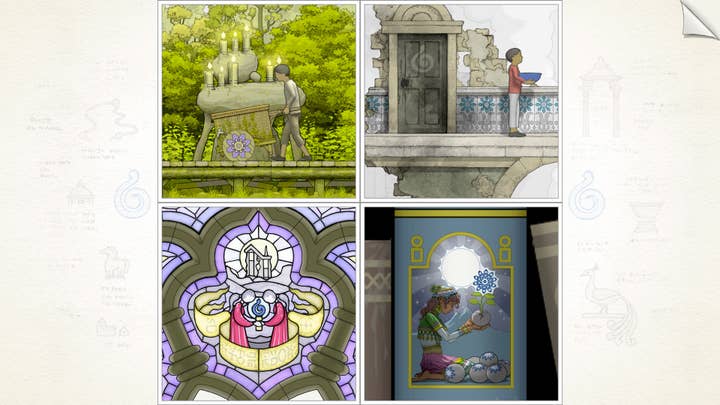

Buried Signal: "Every piece of Gorogoa was a new problem"

After his excellent debut Gorogoa, Buried Signal's Jason Roberts looks towards a far less difficult second album

A prominent indie designer once explained the Game Developers Conference to me like this: E3, PAX, EGX and their ilk are the race, but GDC is the victory lap. The most distinctive creators from the previous year are given the biggest stages, and what often feels like the entire games industry gathers to reflect on their achievements - to gain a little insight into how brilliance works.

That is very much the feeling during the talk given by Buried Signal's Jason Roberts, the one-man band behind the singular puzzle title Gorogoa, his first ever published game. The room, one of the largest at GDC, is teeming with people, his arrival on stage greeted not just by applause, but a generous amount of enthusiastic cheering and hollering. Seven years after work on Gorogoa started in earnest, Roberts is at GDC to take his victory lap.

"In a sense, making an unwise decision among wiser people will result in uniqueness"

"A little bit," Roberts concedes, when I ask if that's how the crowd's enthusiastic reception felt. "But I still stressed a lot about the talk. It's the first big talk I've done at GDC, and I didn't realise how much work goes into it. I'm glad I did it, for the experience. But I don't think I'd advise anybody else to."

Roberts' speaks with a measured, even tone, and one gets the impression that he's no great lover of the spotlight. In addition, the level of interest in hearing him explain his process since it launched to rapturous reviews in December 2017 is difficult to square with the way he sees the game. Gorogoa is, he says, "a non-verbal experience" by design, and one created almost entirely on his own.

"When I try and talk about it, it's just this confusing word salad that comes out of my head," he continues. "I don't know which of the things I did I should encourage people to emulate, and which I shouldn't. The overall theme was about my struggle, over the years, to make the content of the game [and] the themes work with the mechanics I had made.

"The lesson, I hope, is about that thought process, by giving an example of what I went through to figure that out. If you build a game with a particular mechanic, not every story makes sense to tell that way... Every piece of Gorogoa was a new problem."

There is no question that Roberts struggled to finish Gorogoa and bring it to market, and that's largely down to a "bespoke" development process that was defined as much by naivety and inexperience as it was by his abundant talent. Indeed, when he created the first demo in 2012, he did so "in total isolation as a developer." No feedback from a peer group, no education in game development; he had never so much as read a book on game design theory. Roberts started with the intention of writing a graphic novel, and simply followed the idea wherever it took him - very often into uncharted waters.

"So I encountered that criticism from other designers - I mean criticism in the constructive sense - after I'd already built something," he says, recalling the moment he showed that demo to people for the first time. "A lot of it was seeing what people said about the demo, and understanding their points, but they were referring to principles of design that I hadn't given a lot of thought.

"The game was hard to make in a way that looks like it was hard to make. It's not like all that effort just disappeared"

"I had to absorb all of that information and still make a finished game, but I was never starting from scratch... A big part of the challenge was working with what I had, and adapting and expanding what I'd already made, because I couldn't start fresh with all of my new understanding."

However, this approach to the game's development - so far away from the finely tuned pipelines indies working with limited resources are encouraged to have - is unquestionably part of what makes Gorogoa feel so distinct. Roberts didn't know the rules, but having that knowledge may have pushed him down safer, more familiar paths. By the time he started to gain that understanding, he was already inclined to protect the core of what he had created.

"Yes," he says. "Details of the production - the way the art is done, the way animation is done - are very inefficient in a lot of ways, and I don't think I would have chosen those methods if I'd had more experience. But, fortunately, the game was hard to make in a way that looks like it was hard to make. It's not like all that effort just disappeared.

"So I suppose, in a sense, making an unwise decision among wiser people will result in uniqueness."

What's certain is that Roberts will not need to feel his way through the creation of his second game. The lessons of the years since he first started Gorogoa will allow him to begin with a confidence and clarity that was impossible in 2011 or 2012. There will be clear benefits to that, he says, but it's not beyond the realms of possibility that something will also be lost as a result of streamlining.

"One of the first things I thought about when making the next game is decoupling the art and mechanics more," he says. "That means I can prototype farther without making any art. It means I can work with other artists, and our work would be cleanly separated. That's a very game designer way of thinking. Gorogoa works the way it does because I didn't know to make that separation. The art and the gameplay are all tangled up, and that's part of what makes it interesting."

"I don't know that what's good about my games would be enhanced by expensive 3D graphics. Or it wouldn't be enhanced enough to justify the cost"

He will also have more resources at his disposal, too, thanks to a level of commercial success for Gorogoa that he describes as, "a relief in this market." The next game will take much less time to finish, but he doesn't envision it being notably bigger in terms of scope, or anything that would require a large team - save for a proper animator, one of the many functions Roberts performed on Gorogoa.

"I was like a director who cast himself, so I had to work around my own limitations," he says. "I'll enjoy letting go of that part of the process. And the next game may have a more direct, impactful storytelling. For that I need a real animator.

"But [giving up] my low burn-rate, that would be giving up one of my advantages in the marketplace. I don't know that what's good about my games would be enhanced by expensive 3D graphics. Or it wouldn't be enhanced enough to justify the cost."

Roberts is understandably wary of being seen as committing to anything less than six months after releasing his first game, but he confirms that he will explore the central concept of Gorogoa in at least one more game.

"Multiple, interrelated panels," he explains. "There's a different and more complex version of that idea that I wanted to explore, which was an earlier step in thinking about Gorogoa, where I just threw out all of this complexity, which I want to go back to. There's more to do there. I boiled down Gorogoa so much mechanically that I left other stuff. I think it will take place on a plane, and you'll have windows into stories that interact, but in a very different way than Gorogoa.

"The thesis of not knowing the rules makes you go in interesting directions, I think that's right. But I also think that, where I'm coming from and the kinds of interests I have, I'm more interested in the space between games and comics, or the idea of games that sprawl out on this plane with multiple panels that interact.

"That is an area that doesn't seem to interest other people as much. As long as I continue to explore that kind of thing, I hope the games will still be different."