Autonauts: Motivating players without conflict

Former Grand Theft Auto creative director Gary Penn discusses changing relationship with violence and conflict with his new game

Almost without exception, video games feature conflict. Whether it's eviscerating endless goons or building shelter for when night comes, external pressure creates conflict, driving players through the game and shaping their experience.

Even ostensibly peaceful games like Minecraft or Stardew Valley have monsters that lurk in dark corners of the world, ready to ruin your day. AI coding and colony sim Autonauts, however, has taken a distinctly different approach, where all conflict is essentially of the player's own design. In Autonauts, you are your own worst enemy; not only do you solve your own problems, you create them too as you attempt to optimise your increasingly convoluted production pipeline.

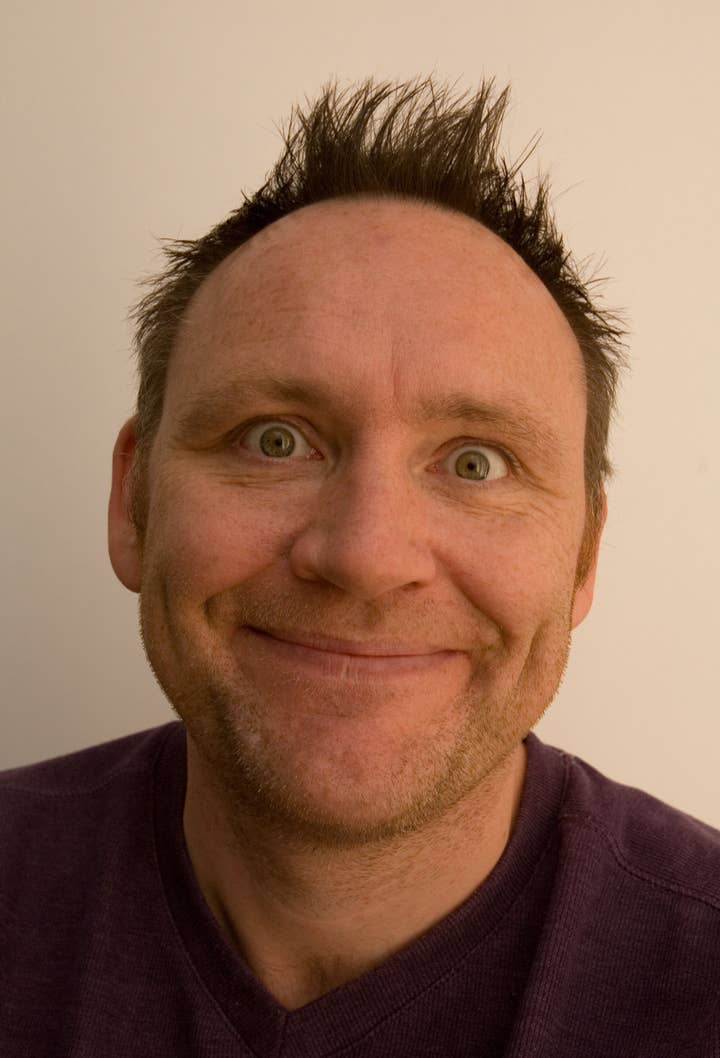

Released last week on PC, Autonauts comes from a two-person team within Dundee-based Denki Games, comprised of DMA Design alumni Gary Penn and Aaron Puzey. As creative director for the original Grand Theft Auto, Penn is one of the original architects of modern sandbox games. However, his previous work of violence and carnage has given way to Autonauts, a game with so little conflict it was actually a "real pain the arse" to design.

Autonauts was "love at first sight" Penn tells us, after technical director Puzey knocked together a prototype. The game sees players colonising a planet, developing technology and developing complex systems to automate processes along the way. Though promoted as an AI coding game that can help teach the fundamentals of programming, that was never their intention.

"We didn't set out to make that," says Penn. "We did the initial prototype and that's when we noticed... It's not that close to real coding, but you do definitely pick up a lot of the principles and the ideas of interacting systems... So as a happy side effect, it's a really nice one to have."

It's been over 20 years since the original Grand Theft Auto (21 today, in fact), and despite his involvement with games like Crackdown 3, Penn says his relationship with violent video games has changed. He says this is partly thanks to getting older and having kids, but also because of the industry's continued over-reliance on violence. At this point it's like punctuation or the chorus of a song, he says.

"A lot of the violent stuff that's out there doesn't really explore violence in a particularly interesting way," he continues. "By which I don't mean violence as a good thing, I mean that 99.9% of it seems to be gratuitous. and gets very banal as a result.

"I don't think anyone gets desensitised to it. I guess the mundanity is a degree of desensitisation, but I think people would still find violence a repugnant thing. But I think as you get older and your perspective on life changes, you realise there is more to it.

"So we ended up with less and less threat, but more and more to do weirdly"

"From an artistic point of view it's stuff that's worth exploring, but no one does it in a particularly interesting way. A lot of it is just the same old stuff over and over again, and you get it with a lot of games that have interesting storylines, but it turns out the main way of interacting with the game is shooting."

Grand Theft Auto may be the poster child of video game violence, but Autonauts couldn't be a further departure from that world. The game sees players automate every aspect of their colony in order to build, grow, harvest, or whatever else you can think of. While Penn says they experimented with things like wolves and cataclysmic weather events, nothing felt right.

"It didn't really seem to resonate with anyone, it just felt wrong and misplaced," he continues. "So we gradually extracted these things. But also, because you've spent so much time investing into training and teaching these robots to do things, the last thing you want is for a torrential weather event or some other aggressive menace wiping the whole thing out. It's very well having a save game, but it's quite a miserable thing to happen. So we ended up with less and less threat, but more and more to do weirdly."

Autonauts tries to lead you rather than push you; Penn describes it as "less prescriptive" than most games, and being more about playful experimentation. But making a game without conflict presents a fairly unique set of challenges when it comes to driving the player forward, and Penn says there are no easy answers. It's a game where the possibilities slowly unfold; players need to decide what their own objectives are, and figure out the best way to make them happen.

After half a dozen frameworks and game structures, none of which really worked Penn admits, they settled on a fairly stripped-back and simple approach, trying to avoid overcomplication or tedious simplicity.

"The stuff you do yourself isn't painful," says Penn, "and it doesn't last that long if you automate stuff, but the contrast is really quite marked... Once you get that, there are some really joyous moments where people realise you can automate everything, and they don't have to do it themselves...

"And that's been the hardest balance of all actually -- driving you forwards but still doing what you want. We resisted putting a tutorial in but did eventually because not enough people were getting it themselves. We had to give them the direction, or enough rope to skip. That's been difficult."

Autonauts has gone through extensive public testing, with the devs watching live streams obsessively trying to figure out the many ways in which it might be broken. Repeatedly, the question around player guidance was causing problems: it's an open game, but without conflict to drive the player in a given direction, they often wound up rudderless, and trying to guide them felt "really, really bad."

"It's why the tutorial felt a bit weird at first, but we tried to keep that fairly light and open, which has been a pain in the arse," says Penn. "When you're building an open world game, there are so many possible edge cases you've got to cater for and you can't predict them all, so we've had to try and keep them as constrained as possible and flexible as possible, and that's caused no end of problems... We've ended up with what we've ended up with, because we couldn't sit there forever trying to figure out the perfect game. You've got to ship something, and I like that old saying about games being like fruit, and having an expiry date. I think it's quite a lovely idea."