The difference in game dev for love or money

Earth Analog developer Roy van Ophuizen has found more success making games since he stopped doing it for a living

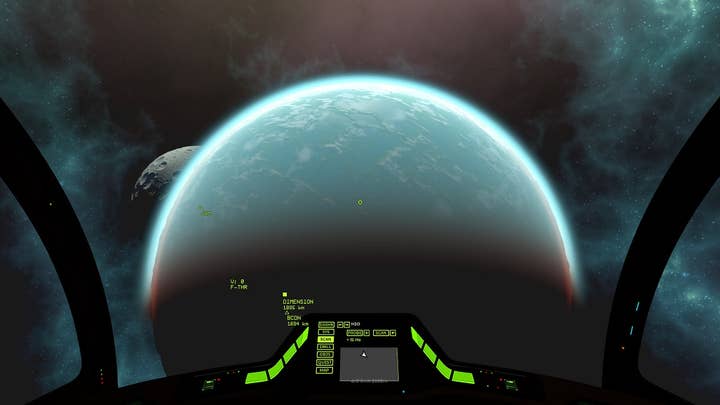

Last month, Roy van Ophuizen released the space exploration game Earth Analog on Steam.

And while the genre seems to be trending up with some notable acclaimed entries in recent years, it's not difficult to see what makes Earth Analog a little different.

In Earth Analog, players flying through space have a device that can bend space-time, changing the planetary environments in real-time in ways that have an assortment of implications for the gameplay.

"It has an aesthetically pleasing effect, but it's also a means to unlock pathways within the game, so it also has a gameplay effect," Van Ophuizen tells GamesIndustry.biz. "And you have to take care, because if the environment changes, you have to take care not to crash or something."

Van Ophuizen explains that the seed for Earth Analog was planted in 2015 when he learned about an image rendering technique called ray marching.

"It's basically a form of ray tracing," he explains. "But you don't need ray tracing hardware for it. It allows you to visualize complex mathematical functions. For instance, these fractals, strange repeating patterns."

Van Ophuizen acknowledges the technique still requires a powerful GPU, and that it's not entirely brand new to the world of games.

"It's often used for things like clouds in other games," he says. "Whenever something volumetric needs to be visualized, it's often done with ray marching. It's difficult to use in other games because the way the world is created doesn't work with polygon meshes, which are basically the fabric of most games."

The only polygons in Earth Analog are the graphics for the player's cockpit. Beyond that, the game is one prolonged experiment with ray marching, testing out gameplay that wouldn't be practical using more conventional rendering techniques.

"The technology allows for dynamic terrain," he says. "It's pretty easy to change. Because these fractals are formulas, you can just change the parameters and the whole environment changes dynamically. That's something more often in games is not possible because they use all kinds of optimization structures that rely on the environment to be static."

It's been said that shipping any game is a small miracle, perhaps doubly so for Earth Analog considering it's a mostly solo effort from a developer who gave up on game development as a career more than a decade ago.

In 2007, Van Ophuizen started Funcraft Games with an eye toward developing casual games for the masses. He worked on Ballhalla, a puzzle game that caught the attention (and publishing support) of Sandlot Games.

And while Ballhalla would not have appeared out of place grouped alongside successful casual titles of the time, it arrived on the cusp of the iPhone era but before the App Store launched.

"I think we were too late for the PC casual market," Van Ophuizen says. "Maybe a year too late. And we were too early for the mobile casual market."

By the end of 2008, he had left the games industry for a software engineering job and put game development behind him because it just "wasn't lucrative enough to sustain the business." The new job was better at paying the bills but still stressful, and as the years went by, Van Ophuizen says he found himself needing a creative outlet and a way to relax.

"In 2015, I picked it up again more like a pastime activity," he says. "I make games in my [free time] next to my job. So I have a full-time job and in the evenings I create these games."

While he had the idea for Earth Analog fairly early in his return to game development, it wasn't his first project back. He returned to development with a couple iOS games before moving to Steam with the sandbox physics game Stacks TNT and the procedurally generated bullet train game Hypertrain.

All in all, game development as a hobby has suited Van Ophuizen.

"It's much more comfortable right now since I don't depend on the income," he says. "That really makes a difference. It allows me to experiment more, to try different things, go for new ideas and build what I like to build. There's no stress in creating the game anymore, and I think that benefits the games."

While plenty of developers in a similar situation have run into work-life balance issues by putting game dev on top of their day jobs, Van Ophuizen says he's not one of them.

"Developing games gives me energy," he says. "It doesn't cost me anything. It allows me to balance life better because I have a creative outlet and I have something to do in the evenings. It enriches my life."

Van Ophuizen mostly works alone, contracting and collaborating in parts to help round out development. But he also self-publishes, handling all of the marketing and community management chores for his games on his own.

"It can be a bit stressful, especially the days after the launch," he says. "You have to be prepared for a lot of feedback. You have to be present, to show yourself on the forums, and to take people's feedback seriously... You have to get through it and handle each problem one at a time, you have to release patches, and be present with some Twittering."

Again, while some devs may find that process distasteful, Van Ophuizen says he finds it rewarding. In fact, we only found one aspect of making and selling games Van Ophuizen seemed to show any aversion to. While he would love to see Earth Analog ported to next-gen platforms, that's a task he admitted he'd probably let some other company handle for him.

So if he's primarily making games for the creative outlet and relaxation and he gets through the development process itself, how does he judge the success or failure of Earth Analog's public release?

"That's a difficult question to answer," he says. "In terms of financial success, the game didn't cost a lot of money to create because most of it I just made myself, basically. I had to license some stuff but it doesn't involve large chunks of money. There's financial success because I already earned a lot more than I would have expected.

"But more important is just that people enjoyed playing the game. And what I really like is when somebody takes the time to play the game -- ten hours or something -- and then gives a positive review, that's the most satisfying part."