GoldenEye, Mario and how to succeed in the world of nostalgia

There's a huge market of 30-somethings eager to replay the games from their youth, but getting it right can be hard

It was the most talked about new game of the week, if you can call a leaked, unfinished 2008 remake of a 1997 N64 game 'new'.

GoldenEye, one of the last potential untapped goldmines of 1990s nostalgia, was remastered for Xbox 360 way back in the late '00s. But it got stuck in a licensing quagmire that left it abandoned on company laptops, only for it to somehow make its way onto the internet two weeks ago.

If you believe the reports, Nintendo was reluctant and EON was never a fan of the game. Only last week, IO Interactive -- the new licence holder of the James Bond IP -- quoted Bond boss Barbara Broccoli disliking the old game tie-ins for being "violence for violence's sake." You know, unlike the films.

Regardless, for gamers desperate to play it, it's out there now. And for those who prefer an official release, well, we can hold on to the feint hope that all the delays to the new Bond movie will encourage the powers that be to take the easy money and give the fans what they want.

I say easy money, because the word on social media is that it is a good remaster, and we know how lucrative nostalgia can be. Earlier this month, Nintendo revealed that in just over three months its recent collection of 3D Mario games had surpassed 8.32 million shipments worldwide. Super Mario 3D All-Stars is a pretty basic port job, with little added to the game outside of some soundtrack options. Nevertheless, Nintendo felt comfortable slapping a $60 price tag on it and watched it become the second biggest new Switch game of that year.

The market for remakes, sequels, reboots, spiritual successors and anniversary collections is a multi-billion dollar opportunity

There are countless examples of nostalgic hits, from Crash Bandicoot: N.Sane Trilogy to Nintendo's micro consoles, which have been emerging for the best part of half a decade. Anyone that felt this was destined to be a fad wasn't paying attention to what's happened in other entertainment industries, where the nostalgia for 1980s movies has evolved into nostalgia for 1990s movies and now into 2000s movies. The market for remakes, long-awaited sequels, reboots, spiritual successors, reunion tours, anniversary collections and so on is a multi-billion dollar opportunity.

Yet to describe capitalising on nostalgia as 'easy' is doing a disservice to the decisions, planning and execution that goes into turning old classics into modern hits. By looking at some recent examples, however, it's possible to see what works and what doesn't.

Who is the audience?

The first thing to consider with remakes is the audience -- we are not talking about the younger generations, who typically have more time but less money.

There's an assumption that nostalgia is driven by people approaching middle-age and wishing for the 'good old days' of their youth, and it's likely that's a big part of it. But I'd argue another element is that, as you get older, you typically have less free time, and so you're more likely to turn to entertainment you know you'll enjoy rather than gamble on something new.

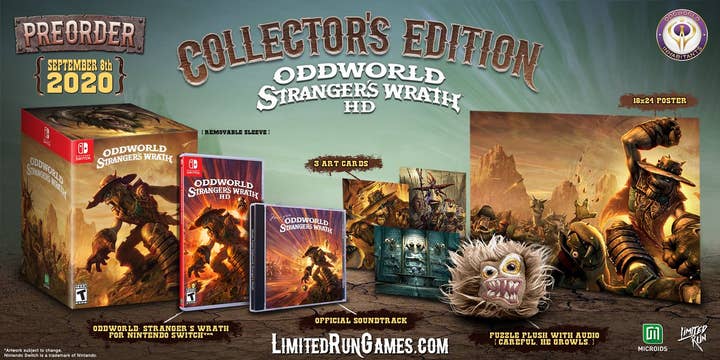

This audience doesn't necessarily want something radically different, and it is also an audience that, generally, has more disposable income -- there's no need to try free-to-play monetisation models. You can even build high-value special editions, on which the likes of Limited Run have been able to build entire businesses.

The question to ask when thinking about audience is how important is it to attract a new generation of fans. To do this is risky and will involve significant investment, but there are examples of games that got it right, and have delivered ongoing success after the initial nostalgic buzz.

What game should you remake?

The nostalgia market is not exclusive to the blockbuster brands like Sonic and Resident Evil. There have been numerous examples of profitable releases based on more niche titles, from Turok to SpongeBob Squarepants. Having an audience of some description is important, of course, but two other metrics to consider are time and quality.

You may think it's stating the obvious to make sure you are resurrecting a good game, but we've seen examples of companies picking the wrong product, presumably because it was easier to do. In 2019, Sega brought Super Monkey Ball back; the franchise built an audience on the back of two excellent Nintendo GameCube titles, but the remaster was of the Wii game, Super Monkey Ball: Banana Blitz.

Banana Blitz isn't the worst in the series by a long stretch, but it certainly wasn't the game people were clamouring to see come back. It received a muted reception at launch.

The other thing to consider is the age of the game. The sweet spot seems to be games that are between 15 and 25 years old. If someone was in their late teens when they played a game from that era, they're now in their 30s or early 40s. As mentioned before, these people will be in a very different stage of their lives, and eager to pop back and remind themselves of the things they enjoyed growing up. That's not to say your ten year-old game can't work as a remake, but the bigger hits have typically been a bit older.

What if I don't have the IP?

If there's one lesson GoldenEye teaches us, if you don't have the rights to remake the game, don't do it. There are numerous examples of fans going out to remake a game they once loved and finding a cease and desist on their doorstep. Of course you could go out and try and obtain the rights, but that's a far more complicated article for another day.

There is, however, another option: The spiritual successor. This tends to work if you and your team happened to be the creators of the original brand you're trying to resurrect. There are three recent Kickstarter triumphs built around this concept: Bloodstained: Ritual of the Niht (Castlevania), Mighty No.9 (Mega Man), and Yooka-Laylee (Banjo-Kazooie).

A game's original audience tends to be more forgiving of ageing visuals, control schemes, camera angles and design choices

All three are from some of the people behind the original games, and they didn't hide the fact they were effectively building spiritual sequels to those classic titles. This can be successful, but the challenge here is delivering against expectations. Some of the team members may have been the same, but these games didn't have the budgets of rival products in the genre -- they were ultimately indie titles, albeit ones built by people with vast levels of experience.

With a need to drive Kickstarter revenue -- all three were crowdfunded -- the campaigns focused in on what these games were inspired by, and this set a very high bar from the outset. Nostalgic fans want to experience games that look, feel and play as well as they remember, and their memories may not be entirely accurate. In order to live up to those expectations, ensure you've given yourself the time and budget needed to deliver.

Remaster vs. Remake

Remasters are the most common form of nostalgia play. These games look largely like they did at launch with some HD visual upgrades, and occasionally a more contemporary control scheme. These products are almost entirely targeted at the original audience.

A reimagining can be big business: 2019's Resident Evil 2 sold more copies than the game it was based on

Aspyr's remastered Star Wars Episode 1: Racer is a prime example. A game based on a scene from an unloved Star Wars movie is unlikely to draw in many new fans, but those that remember the high-quality futuristic racing title will likely be interested in seeing how it holds up. As a result, investing significant resources in fully remaking the experience wouldn't make sense.

A game's original audience tends to be more forgiving of ageing visuals, control schemes, camera angles and design choices. They've grown up with games looking and playing this way.

The next level up is the remake. A good remake will appeal to both old and new fans. For old fans, these games will look and play exactly like they remember them, even though they're actually significantly improved. For new fans, a good remake will feel like a brand new, modern gaming experience. The best recent example is Tony Hawk's Pro Skater 1 + 2 -- the levels, characters, challenges and even music is the same, but it has been rebuilt with excellent visuals, impressive technology, some new tweaks under the hood, and modern control schemes based on later games in the series.

If you can get the quality right, and draw in enough new players, you may find yourself with a rejuvenated franchise.

What about a new audience?

It's inevitable that some new players will give your remake a try, but to really win over a new audience, you'll need to think bigger. One approach is the "reimagining," where a developer rebuilds an entire game from scratch, often deviating significantly from the source material.

Two recent examples of this are Resident Evil 2 (2019) and Final Fantasy VII Remake (2020). These games are big-budget productions, and though both were largely successful, they proved divisive within some fan groups that just wanted to play the old games on new machines. There are ways around this. When developing the new Resident Evil 2, Capcom almost introduced a camera style designed to mimic the 1998 original. The unreleased GoldenEye remaster featured a mode where you can switch to the 'old' visuals, which would satisfy purists.

A reimagining can be big business: 2019's Resident Evil 2 has sold more copies than the game it was based on, while Final Fantasy VII Remake was greeted with such excitement that Square Enix is planning a whole series of games.

Yet changes are always risky. Just look at the reception to last year's Warcraft 3 remaster, or the XIII remake. Fans were dissatisfied with the changes and let the developers know in no uncertain terms. The XIII remake did such a poor job for fans that some went out and rebought the 2003 original instead, which led to the old game charting higher than the new one when it was released in the UK.

What are the downsides?

Rejuvenated classic games can be lucrative, but full comebacks are rare. There has been a few -- such as Wolfenstein, Luigi's Mansion and Diablo -- but the majority make a brief reappearance before vanishing again. Yes, Resident Evil 2 and Final Fantasy VII have delivered big numbers, but those franchises were far from dormant, and they both have a fanbase that crosses generations.

Tony Hawks Pro Skater 1 + 2 got off to a strong start, but the news that Vicarious Visions is now on a different project suggests it wasn't quite enough to warrant a full series relaunch. Shenmue 3, one of the few examples of a series getting a full sequel rather than a remake, received strong backing from hardcore fans on Kickstarter, but failed to bring in many new players when it was finally released in 2019. And after two popular remasters, Activision finally decided to invest in a proper Crash Bandicoot sequel, but last year's Crash Bandicoot 4: It's About Time hasn't delivered anywhere near the same level of success.

It's the same in TV and movies, too. For every Doctor Who or Jurassic Park that manages to achieve a successful and sustained comeback, there are countless Ghostbusters, Terminators and Aliens that have not -- irrespective of quality. The reality is that people like to reminisce and remember, but that doesn't mean they want the glory days to come back. In music, ageing rockstars will always sell out arena tours playing the classics, but their new albums won't always make the top ten.

The GoldenEye remake that never officially saw the light of day was not about the future of the studio, or James Bond games, or a statement from Xbox about where it was heading. It was just about giving people in their mid-30s something to smile about, while making a bit of money in the process. The nostalgia market in video games is lucrative and increasingly popular, but it's about celebrating video games' past, not defining its future.