Stadia Makers say transition to Google's platform challenging, but rewarding

First studios in the program describe the pain points and perks of developing for the cloud gaming service

When Google first announced the Stadia Makers program back in March, one of the main goals was to encourage more independent developers to publish -- and especially self-publish -- on its new cloud streaming platform and service.

It's a challenging enough task for a smaller studio to consider other platforms beyond their original scope, and in Stadia's case, the ask was even greater due to the potentially daunting nature of new technology.

To help offset this, Stadia offered support: up to five physical development kits for each studio selected, an unspecified amount of funding, and technical assistance from Unity to develop in its engine for the platform.

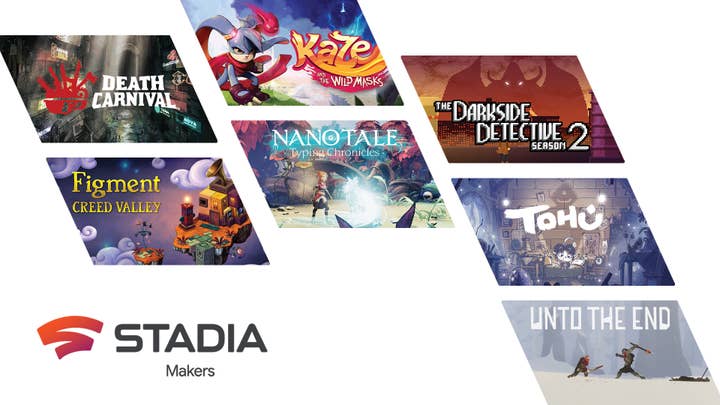

Six months later, and Google has announced its first class of Makers, seven studios working on projects to bring to Stadia in the future. All are small to mid-sized independent studios, and all have at least a few years of experience under their belts and prior shipped titles.

Speaking to GamesIndustry.biz, developers from each of the studios cited a myriad of reasons for applying to the program. Some were invited by Unity or Stadia itself based on past work or relationships, several already were sold on the promise of cloud gaming, and a few were simply curious.

"The bet for us with Stadia is the opportunity to bring the game in front of a larger player base with different tastes"

Bruno Urbain

One incredibly common thread the developers cite in the appeal of both the Makers program and Stadia itself was the platform's potential reach.

"The most appealing factor was the fact that Stadia could be enjoyed by anyone with a browser without the need for a dedicated console," says Dima Venglinski, CEO of Fireart Games working on adventure game Tohu. "This meant Tohu could be played by a huge audience on a global scale, lowering the barrier to entry to our game."

A bigger audience is an obvious draw on its face, but Bruno Urbain, CEO at Fishing Cactus notes a distinct advantage for his studio's games for Nanotale - Typing Chronicles to being on Stadia.

"Nanotale is quite a unique game. First, it is a typing game, and second, it is quite a chill game to play. You can play at your own pace very much like Epistory, our previous typing game. Our core player base is composed of indie gamers with a large proportion of female players. That audience is looking for a strong story game without direct violence, which is quite distant from mainstream games.

"The bet for us with Stadia is the opportunity to bring the game in front of a larger player base with different tastes and continue that trend."

Several of the developers are candid about the process of bringing their games to Stadia. Stadia, they say, is not devoid of challenges -- no platform is. Venglinski says he was pleasantly surprised to find that it wasn't as challenging to port Tohu from PC in Unity over to Stadia as he thought it would be.

"We were initially concerned that Stadia SDK would have compatibility issues with some middleware, but we were glad to find out that they were already supported," he says. "If you have any custom solutions, like shaders, then this would need some extra work, but Stadia already supports most of the native solutions provided by Unity and Unreal."

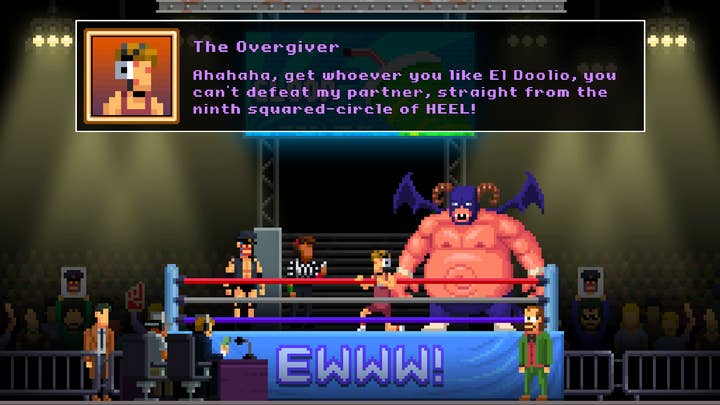

Ben Marquez Keenan, developer at Spooky Doorway working on Darkside Detective Season 2 called Stadia "kind of unfinished in a few ways," but said that the support team had been very responsive in helping them deal with challenges.

"In terms of infrastructure, we kind of naively assumed that spinning up cloud instances for deploying and testing builds would be a doddle, but that turned out to be quite awkward because of our (by no means unusual) setup of working with the platform through our publisher," he says.

"It's also important to note that even though Stadia is running a Linux distro under the hood, games still go through the Stadia platform for all common tasks like saving/loading, logging in players, and so on. The docs are almost all for C and C++ projects, but we've found the Stadia Development forums on Unity really useful for code examples and info on what generally is and isn't working well."

"We now have a better understanding of how cloud gaming works, especially how UI/UX needs to be adapted on different devices and aspect ratios"

Dima Venglinski

And Urbain adds that developing for Stadia wasn't that much different, in his experience, from developing for a brand new console platform.

"Someone could say 'it is just the exe running in the cloud,' but the tech is much more complex than that and requires a fine technical understanding," he says. "To make the system as stable and enjoyable for their users, Google asks the game to comply to a certain level of quality which is very similar to what one can find on consoles. Those are called TRCs (Technical Requirements Checklist).

"While developing for Stadia is not complicated when you have console experience like we do, it requires the smaller developer to comply with a quality threshold, which is not that trivial and can be counted in several man-months of work. I see this as a good thing for a new platform, streaming or not."

Both Urbain and Keenan say that the support of the Stadia Makers program enabled them to add more time to the project, with Urbain suggesting the time was being used to bring post-release features into the initial release, and Keenan saying his team used the time to work around difficulties that COVID-19 caused regarding testing the game with large groups of people.

_RcFVQe9.png?width=720&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp)

Venglinski notes two other advantages his team reaped from the program. The first is that Fireart Games was able to hire three new people to work on the port, giving the rest of the team time to polish the core game.

"More importantly, we now have a better understanding of how cloud gaming works and how it is enjoyed by our players, especially how UI/UX needs to be adapted on different devices and aspect ratios," he adds.

The seven games by the first class of Stadia Makers will begin to launch in the fall of this year with Tohu. Death Carnival from Furyion and Unto the End from 2 Ton Studios will follow in the winter, and the remainder -- Figment: Creed Valley from Bedtime Digital, Nanotale, The Darkside Detective Season 2, and Kaze and the Wild masks from PixelHive and Soedesco -- are due in 2021. In total, there are 15 games currently in the program, and applications are still open.

Stephen Danton, game designer at 2 Ton Studios, encourages developers interested in the kind of support Makers is offering to apply.

"I think the industry is going through an interesting transition across a lot of fronts," he says. "What it means to be a gamer and game maker is very different than it was five, ten, 15 years ago. Games are getting bigger and more expensive -- even handcrafted games like Unto the End. Making them now demands nearly inhuman levels of commitment and sacrifice. Is that sustainable? Is it really producing the best experiences for fans or for the art of games?

"I think we're going to see some very big changes in terms of how games are made, marketed and seen by both gamers and non-gamers. In such a world it's going to be increasingly important that programs like Makers exist to ensure games large and small have a voice and can reach the right audience. Being part of Makers gives Sara and I -- a husband and wife studio -- a chance to be part of the conversation. That means a lot to us and we really appreciate it."