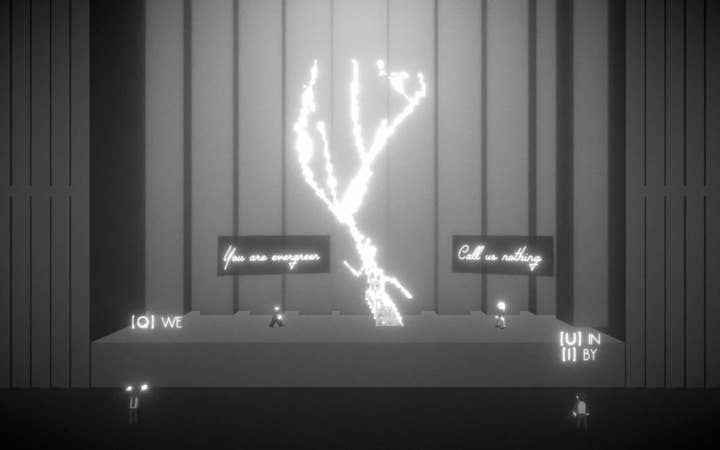

Conducting the interactive opera of Evergreen Blues

David Su and Dominique Star on the musical design of their free, co-op song suite

The creators of Evergreen Blues, a game where two players can choose lyrics for characters to sing to one another, were musicians before they were developers. Naturally.

David Su and Dominique Star originally met playing in a band together. Over time, both also became interested in games as an exploration of musical interactivity, though they took different paths to eventually get to what would become the free, melodic game that recently demoed at PAX East.

"I was doing a lot of experiments with musical interactivity and audience participation for live performances, and I remember playing Biophilia followed by The Stanley Parable and being like 'Whoa, games are the perfect medium for exploring this kind of stuff'," Su says. "The first game I made was this 3D platformer where you're basically just traversing through different sections of a song.

Star adds: "I had a young and embarrassing start in games, with modding this game from the early '00s called Babyz. Yes, it is a baby simulator. No, I will not elaborate. From there I had a natural progression to The Sims, which is where I started learning about skins and meshes. For me, the feel and style of the game is really important.

"The way that music affects your emotions without you realizing it -- that's similar to the way that games allow players to express themselves"

David Su

"As far as our own games are concerned, David started bouncing ideas off of me and I began helping him find some cohesion in the narrative. I approach game development very much from the player side of things. I'm almost constantly playing a new game, whereas David comes more from an artistic and mechanics mindset."

Evergreen Blues isn't the first game the pair have made together, nor is it even their first musical game. Su and Star first collaborated on a game called Seasons (季节) in 2018, which has a similar mechanic of choosing song lyrics line-by-line.

A year later, while working on his master's thesis, Su suggested they explore the mechanic further, as well as add a multiplayer component. That experiment -- supported by the mentorship and feedback of composer Tod Machover, Harmonix co-founder Alex Rigopulos, and digital artist Zach Lieberman -- led to Evergreen Blues, a playable suite of six interactive songs where one or two players can create songs with explicit, player-driven narratives.

Why focus on music as a mechanic across multiple games? Su says it is down to the natural similarities in how both music and games affect their audiences.

"I feel like music and games both have this fascinating subconscious effect," he says. "The way that music is able to affect your emotions in different, subtle ways without you necessarily realizing it -- that's similar to the way that games can allow players to express themselves, to create their own experiences, without the player necessarily thinking about it in those terms... Combining the two, seeing how music and gameplay can intertwine in various interesting ways, that's become a bit of an obsession for me personally."

Of course, Evergreen Blues is far from the first game to explore music as an integral part of its narrative, or even as a mechanic. But its total reliance on its six songs, and specifically the lyrics and how the player chooses them, added both a limitation and a unique element of freedom for Su.

"We often work with music that has lyrics, so in a way that's the most freeing, because then you have the whole spectrum to play with"

David Su

"With music you're able to paint more abstract pictures and draw more on the audience's feelings directly without tying that to a specific image," he says. "On the other hand, sometimes you do want a specific image, which is where dialogue or even any kind of text can be useful.

"We often work with music that has lyrics, so in a way that's the most freeing, because then you have the whole spectrum to play with, and also just the interaction between music and words can be so powerful. I will say that one limitation of working with lyrics is that it becomes quite difficult to fully localize without significant resources, since subtitling a song in a different language is such a different experience from hearing it sung in that language."

Star, who is a singer, is responsible for the game's vocals, which wait for the player to make a selection before playing and yet -- at least in the demo I tried at PAX East -- always seem to fit in appropriately with the tempo and mood of the lines before.

"This was recording a single word five or six times individually, and you had to make sure that the performance matched the other words so it isn't jarring or obvious they're different takes when you put them together," Star says. "It was a lot of work and I'm pretty sure when we were done I said 'I'm never doing that again'."

That balance is tricky enough when it's a single player making the lyric decisions, but Su describes an even more complex situation once the two characters begin to sing together.

"We did struggle a lot with how to let the two different characters sing their respective melodies at different rates while still maintaining overall song structure and coherent chord progressions," he says. "For example, in one playthrough, character A might complete an entire verse while character B is still on the first line. In another playthrough, character B might finish a verse while character A is halfway there. In another, they might finish at roughly the same time.

"At some point, we tried to turn this into a longer experience, but it ended up not being what this game wanted to be"

David Su

"So to accommodate all these potential timing scenarios, we devised a two part solution. The first part was to use asynchronous harmonic progressions, where individual choices can trigger changes to the underlying harmony of the song, so now the song follows the players rather than vice versa. The second part was to create checkpoints at particular points, so that one player couldn't get too far ahead of another. That second part definitely feels less elegant than the first, but it did the trick."

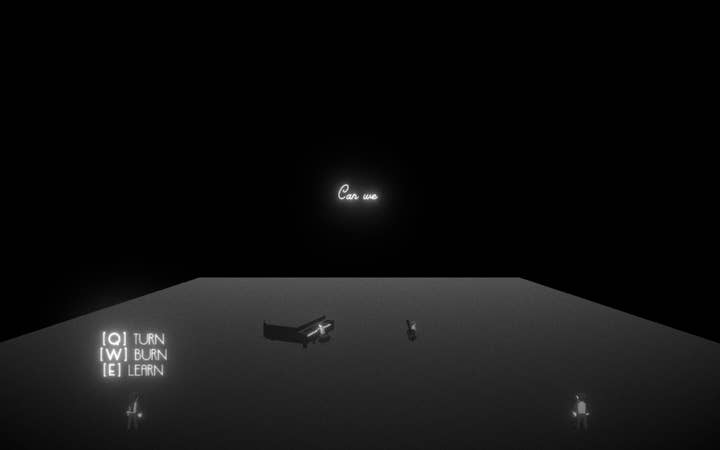

Evergreen Blues is its songs. There's no explicit narrative tying them together, though the songs have themes that tie together and lyrical choices made in one song can affect those available in others. There are characters who sing and play the songs as the player moves through them, but their roles and connections are largely up for interpretation. It is, as Su puts it, "more about variation in mood than plot."

"There isn't really a concrete story, so the coherence I think comes from repetition and variation of motifs and images from both a musical and lyrical standpoint, as well as the consistency of the central game mechanic. Initially, all there was was that mechanic, but Dominique helped piece things together narratively so that it feels more like a poem than a demo. At some point, we had tried to turn this into a longer experience with more fleshed out characters, but it ended up not being what this game wanted to be."

Is Evergreen Blues a game? Though asking if something unconventional is really a game is a question that can get bandied about in bad faith, Su is frank about the fact that what he and Star have made plays with the definition a bit.

He does tell me the pair are working on another, similar project that's closer to a "larger, more fully-fledged experience." For now, though, calling Evergreen Blues a video game is a helpful shorthand, at least.

"We've been calling it a 'suite of interactive songs,' but sometimes 'game' is easier to say," Su says. "My friend Tamara Duplantis did a talk where she had a theoretical spectrum of how interactive music experiences can be classified, from 'instrument' to 'toy' to 'sound art' to 'game'. I feel like maybe Evergreen Blues falls somewhere between sound art and a game."