From licensing to lunch: How to work with Chinese partners

Unit 2 Games' Hannah Waddilove on some of the less-discussed aspects of targeting the world's largest games market

For many games firms in the West, China remains the biggest untapped opportunity when it comes to growing their audience.

The nation has been the global leader in terms of video games spending for years, but its strict systems and processes for releasing titles have been significant barriers for anyone wanting to reach this lucrative market.

The most efficient route to releasing your game in China is to work with a local publisher or partner, but these can be difficult connections to establish. At the GamesIndustry.biz Investment Summit, Unit 2 Games' operations director Hannah Waddilove offered advice on how to secure such a partnership, drawing on her studio's own experiences securing a $5 million investment from Makers Fund.

Waddilove began by emphasising the size of the market, not just in terms of the revenue it generates but the diverse audience it represents.

"You can't really consider China as a whole when you're looking at it as a market... Some sections of it work almost autonomously"

"The huge population and the huge amount of land [they're spread over] means there is massive variety in consumer behaviour, demographics and things like that," she said. "You can't really consider China as a whole when you're looking at it as a market, you need to consider specific bits. Some sections of it work almost autonomously."

The mobile space is also a prime example of how fragmented the market can be. Dominated by the Android space, there are no less than 10 major app stores and developers need to make licensing deals with each one separately.

Then, of course, there's the challenge of securing a licence to release your game in the first place. Approvals for release were frozen for much of 2018 while the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television was restructured, and the Games Ethics Committee that now handles applications had been working through a massive backlog, and Waddilove says it's still not clear what the long-term impact of this might be.

Even before the restructure, licences were only issued to around 800 games per year and these could take six to 12 months to be processed, so Waddilove warns studios to take long lead times into account.

The intricacies of China's licensing process have been discussed at length before, and are no doubt still changing ever so slightly as the new system regains momentum. But what has rarely been shared, and the focus of Waddilove's talk, was the cultural differences and the subtle but important ways to avoid clashing with potential Chinese partners.

"We don't want to offend people, we want to make sure we're being respectful," she said. "China is unique and the culture can be quite difficult, or at least intimidating -- mostly because you just don't want to cause offence.

"It's worth noting that generally when you're meeting with Chinese companies, they will be doing the same sort of thing in reverse. They will not be offended by silly Western customs, they will generally be accepting as long as you are trying your best. So don't worry too much."

Waddilove says there are two crucial concepts from Chinese culture to bear in mind, the first being 'guānxi' -- a term meaning 'networks' or 'connections'.

"Don't just scribble on business cards and shove them in your pocket. Examine them, read them, be polite"

"Relationships and relationship-building is super important in Chinese companies. There is personal guānxi, which you have with one another, but then there's also company guānxi, so some companies have been going for decades and it's not based on the individual people but on company trust.

"It's really, really important. A lot of the introductions we had were made by companies that we'd spoken to, who were like, 'Oh actually you seem quite nice and while we're not interested in this right now, let's introduce you to this other company that we know.' It's very much about relationship-building."

The other is 'miànzi', which centres around status, prestige and social position or, as Waddilove elaborates, 'saving face.'

"Obviously, even in the West you don't generally call out your boss if they're a bit wrong in a meeting, you take them aside afterwards," she said. "That's even more important [in China], that 'keeping face' and allowing people a way out of things which allows them to save face.

"The classic example is a really simple one: competing to pay a bill in the restaurant. It's like, 'Oh no, I'll pay' and then there's a bit of a sort of fight and then the person with the highest status wins, because they're able to provide for people."

This brought up the subject of dining, something rarely considered in talks about best business practices. If you're travelling to China, you're likely to end up having meals with the people you want to do business with, and it's best to be aware of the preferred etiquette.

"Chinese meals are for sharing," says Waddilove. "It's really accepted to say to your host, 'Would you like to order for the table?' and they'll order a selection of food you can then share, rather than ordering individually.

"As in English Chinese restaurants, the tables are usually circular and there's a seating order. There are two kind of 'head' positions to the table -- one is the chair facing the door, and the other is the chair facing the east. I don't know if you're supposed to carry around a compass, but if in doubt, ask where they would like you to sit. That's always best."

"You're fine to email people, but it's really good practice to message them on WeChat to let them know you've emailed them"

Waddilove also emphasised the differences in how business cards are handled in China. As with many Eastern cultures, these should be handled with respect, given and accepted with both hands.

"Don't just scribble on them and shove them in your pocket. Examine them, read them, be polite with that."

You should also be prepared for multiple trips. Waddilove observes it's very rare to cover everything with a Chinese company in the first one or two meetings.

"There's actually a phrase in Chinese, which roughly translates as 'paying three visits to the thatched cottage', which is about a myth where someone went to a cottage to ask for help and they had to keep going back, and after three times the person relented and gave them the help they were asking for. So perseverance and fortitude are key facets that you need to demonstrate."

Another tip is to take gifts for your hosts, although there are two things to bear in mind here. Firstly, the gifts ought to be small so they are able to reciprocate the gift. They should also be something relevant or personal if possible.

"It can't just be a box of chocolates," says Waddilove. "If they can have any kind of meaning or relevance, that will really help."

There are other challenges for businesses to bear in mind -- the biggest one being communication, which is always tricky when there are language barriers. In Waddilove's experience, very few Chinese people speak English -- you might find only one or two people in big companies whodo. She recommends that developers find a person who speaks English at the firm they're hoping to work with, someone who is passionate about your product, as they can advocate within the company for you.

"You need to keep going until you find that person," she adds.

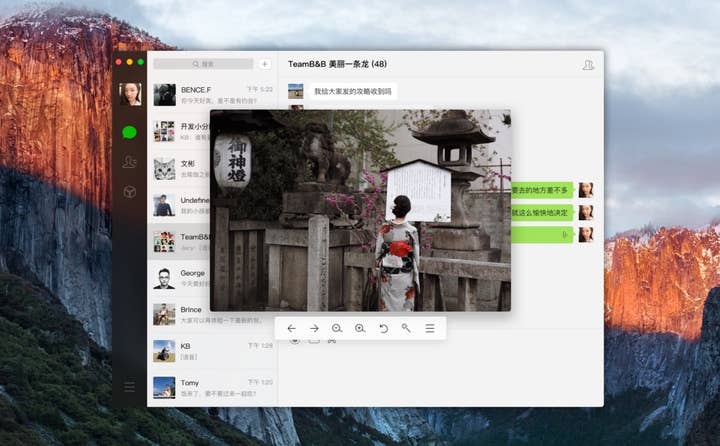

"Also, bear in mind everyone in China uses the WeChat messenger app. Instead of trading business cards, you'll often scan QR codes for people's WeChat. It's often preferred to email, because the firewall means email can be a bit unreliable. You're fine to email them, but it's really good practice to message them on WeChat to let them know you've emailed them."

China's firewall also means a lot of the third-party services Westerners take for granted are blocked -- there's no YouTube, Facebook, Google Drive or Dropbox (to name but a few).

"There are huge opportunities in China. It's a lot of work, but the good news is you don't have to do it alone"

"Companies will often have VPN and be able to access those services, but in general we found what's best is to either ask, or provide multiple routes to the same information," Waddilove says. "For example, if you wanted to share video, feel free to share a YouTube link but then also email or message on WeChat and ask if they want you to just send the file. Then they have the option."

There can also be difficulties when transferring currency out of China. Local companies that have already done business with the West (Tencent, NetEase and other familiar names) will already have facilities for this, but smaller companies who might be taking their first steps out of their home market may not.

Similarly, IP protection is "often a massive concern" for businesses when it comes to China. Waddilove assures it's not as bad as it seems, but there are some "weirdnesses." In the UK, trademarks are filed under a number of classes and if you have protected your trademark under a certain class, no one else can use it. However, China has additional sub-classes and companies can use any name as long as it's not in the same sub-class.

"They've essentially subdivided things into much smaller sections, so you have to be much more specific," Waddilove explains.

"It's also important to note that you ought to trademark not just your company or product name, but also nicknames, translations into Chinese, all these things. There's a lot to consider, and if you are looking to take your IP to China, you're probably better off engaging a lawyer who has expertise in this because it's very complicated and different to the UK."

Waddilove recognises that the notion of dealing with China may seem intimidating, but emphasised it's still something to consider given the sizeable audience it holds.

"There are huge opportunities, there are lots of people in China -- a lot of them love games, especially PC and mobile games," she concludes. "It's a lot of work, but the good news is you don't have to do it alone."