Three million square miles of wilderness: How Silk advances a lost genre

Chris Bateman and Rob Hewson on the '80s-style exploration game's vast world and the choices that drive players through it

Silk is not your typical open-world game. There are no quest markers, fast travel, collectathons, level-gated areas, outposts to liberate, or map-revealing towers to climb.

Instead, it's modeled on the square tile exploration games of the 1980s -- specifically Mike Singleton's Lords of Midnight, which Chris Bateman (founder of Silk developer International Hobo) describes as "the best Lord of the Rings adaptation to not have the Lord of the Rings licence."

Set on the ancient Silk Road of 200 AD, players are given the choice of four objectives (or 'destinies'), which range from simply travelling from one end of the road to the other, to overthrowing the Parthian Empire that dominates much of the route.

The game is presented in first-person with a "neo-retro aesthetic" and takes place over three million square miles of wilderness, which the developers claim makes it the largest hand-crafted open world in gaming history. The previous record-holder was Bethesda's Daggerfall at just under 90,000 square miles, making Silk more than 30 times larger.

"We see it as a gameplay remaster," says Rob Hewson, whose company Huey Games published Silk and handled the Switch port. "You get a lot of games being remastered, but this is actually a genre being remastered -- the lost genre of tile-based RPGs."

Bateman adds that it's not only a tribute to the "incredible bedroom coders" of the 1980s, but also an attempt to continue their work.

"The UK pretty much created the open world genre with four games in 1984 and 1985," he explains. "Elite, which does get the recognition it rightly deserves; Mercenary, which perhaps gets a little overshadowed by Elite; Paradroid, one of my favourite games of all time; and Lords of Midnight, which of the four is almost a forgotten classic because it was never released in America, so not many people know it."

Silk not only emulates the experience of these games, but also advances it significantly thanks to the way technology has evolved in the past three decades. Creating a three million square mile world is considerably easier when you're not restricted to a much smaller file size. And there are so many lines of dialogue, Bateman was rediscovering ones he had forgotten writing when testing the game.

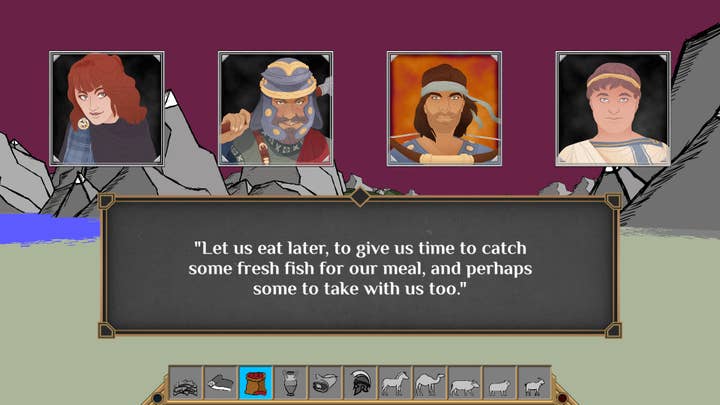

Players lead a caravan of cattle, soldiers and advisors through 200 AD. They navigate in the same way as any first-person game -- albeit locked to the eight compass directions -- and choose who to hire into the party, but that's pretty much the only direct control they have. All other actions are dictated by the advisors.

When trading, for example, you cannot just swap silver for provisions. Your advisors will present you with options and if one of them believes that to be a good trade, you select this option to begin the transaction. It's a system inspired by King of Dragon Pass, and might be more than a little jarring to some players, seemingly limiting their agency.

"It's a knee-jerk reaction to the game at first, not being in control," Bateman admits, "but as you get to grips with the way the game works, you actually find yourself with a tremendous amount of agency because you are deciding where to go and who to hire. You make the decisions between the options that are offered to you. You don't have absolute control over every element; you have to deal with the situation you are facing, and I think that's narratively more interesting.

He continues: "There's definitely a leap of faith involved, because players are used to just being given the keys to the car and driving it themselves. But the advisors themselves teach you how to play it, because they're telling you the things that make sense in that situation. Things like, 'We should buy the silk if we're travelling East'. Everything the advisors say teaches you how to be in this world.

"To some extent, a player with no prior experience of games would have a decent shot at this just by deciding between the choices the advisors are giving them. The traveller's destiny, which is just to travel from one side of the map to the other, is expressly intended to be playable by anyone, even someone with very little experience of games."

In that sense, it sounds akin to something like 80 Days, where players navigate the world and make choices that dictate the course of their adventure, but Bateman is quick to temper this comparison.

"80 Days has a lot of custom-created events, a huge deck of encounters, much the same as something like Sunless Sea," he explains. "These are games where a large part of what you have is a large deck of random encounters. We have a very small number of encounters -- what we're offering is this huge wilderness, this huge world based on 200 AD. I think this is the most historically accurate version of 200 AD you'll find. We're asking you to get to grips with what it's like to be in that world. It's less about the random encounters than it is this experience of what it's like to be a trader or warlord in 200 AD."

Bateman acknowledges that this unusual approach to player agency, combined with modelling the game so closely on a forgotten genre of the '80s, means the venture is, "not an incredibly intelligent way to make a commercial game -- but it's very artistically interesting."

Hewson adds: "We come from a background of being retro gaming nerds. We've got a big retro following, we've funded retro-style games, we've published some, and a lot of our core audience are motivated by memories of Lords of Midnight and that sort of stuff. There are some difficult communications in terms of marketing, but it's unique and it's got some firsts -- like we said earlier, largest hand-crafted open world."

More importantly, last week's launch of Silk marks a personal milestone for Bateman, who has been trying to make a game in this vein since the '90s. He's been distracted somewhat by the more than 50 games he has worked on for other companies -- including Discworld Noir, MotorStorm Apocalypse, Battalion Wars, Stalker: Shadow of Chernobyl and PSVR hit The Persistence.

Having finally set aside time to work on his own titles, Bateman decided it was time to make the game he wanted -- "before the first heart attack," he laughs.

"It's clear that I'm on the back end of my career at this point," he says. "I've already shipped 50 games. All but one of those was somebody else's game, so now I'm just thinking... I really love working for other people's games, I do, it's great, but maybe I've got ten to 15 years left -- I'd like to do two or three of my own in that as well. And I'd like them to be things that wouldn't get made otherwise. I'd like to make some things that, even if nobody gets why I wanted to make it, I'm not just making another Zeldroid game."