Kind Words: A game of lo-fi beats, letters to strangers, and feeling less alone

Popcannibal's Ziba Scott on designing and moderating a game exclusively about being kind to other people

Content warning: This interview contains a brief, non-graphic mention of suicide.

Non-violent games and games that feature kindness as a mechanic may be uncommon, but they're not unheard of. Still, few (if any) turn kindness toward other players into a central or sole mechanic.

Despite being both the focus and title of Ziba Scott's latest game, Kind Words (lo- fi chill beats to write to), the idea for it originally spawned not from the idea of kindness, but as a way to give players something to write about.

In 2014, Scott (who by himself also forms the studio Popcannibal) made Elegy for a Dead World with artist Luigi Guatieri and a studio called Dejobaan. Elegy for a Dead World was a game about walking through landscapes and writing poems with Mad Libs-like prompts, but one particular unused feature stuck with him for some time after the game was in the rearview.

"[Elegy] had a good reception, and one of the things we realized is that people love writing," Scott says. "Give them a chance to sit and write, and they go, 'I haven't done this in forever!' But in that game, no one cared to read what anyone else had written. There was zero interest in that. There were a hundred thousand poems written in that game that no one will ever read.

"So we were trying to figure out what people would want to read. How do we give someone a chance to write something that there will be an audience for, for sure? The answer was to make sure every piece of writing is specifically for one other person who has asked for that piece of writing."

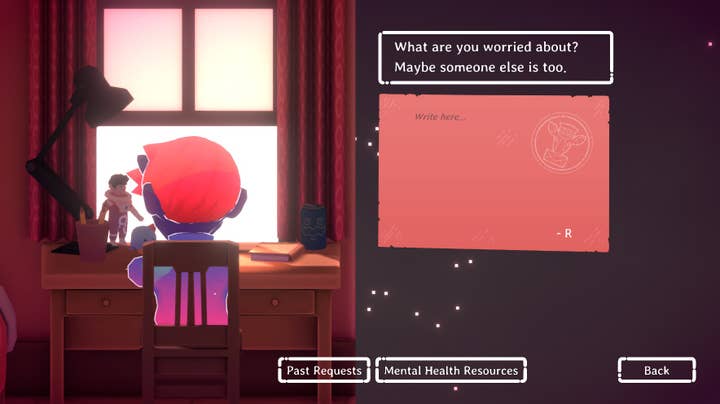

Enter Kind Words, a game where players can write letters of support to other players and request supportive letters for themselves. A cartoon deer who serves as a mail carrier offers some advice on what kinds of requests the player should make, ("What are you worried about? Maybe someone else is too.") then delivers the letters and returns to share the recipient's gratitude when they're received.

Other than the letter writing, the only other "mechanics" to Kind Words are stickers that can be stamped on letters and sent to others to add to their collections and send to others, and a playlist of music that gets a new entry every day the player signs in and sends a letter. It takes place in a tiny room with a character sitting at a desk as a stand-in for the player, but there's no way to control them or interact in other ways with the world.

"[Trolling in Elegy for a Dead World] is like standing alone in a room with a beautiful painting and saying something mean to it. Like, who cares?"

Though "Why is this a video game?" is a question that has often been asked of works like this in a disingenuous manner, Scott has an interesting explanation for why he wanted Kind Words to specifically be thought of as a game and sold on gaming platforms.

"I don't concern myself too much about the definition of a game. I'm perfectly happy for people to call it a game or not a game. There is no score. There is no winning or losing, and it never ends. But making it look like a game was very important to the whole point of it.

"With Elegy, we didn't have a whole lot of trolls. My suspicion is that this was because it wasn't a fun surface to graffiti. You paid to be there, and it's a classy area and so few people are reading what other people write, you don't have an audience. It's like standing alone in a room with a beautiful painting and saying something mean to it. Like, who cares?

"So with Kind Words, I wanted it to be a thing that someone had to pay money for so they were committed in some way. They have to sit down and take a moment and open an app that takes up the whole screen on the computer so they're not elsewhere, they're here in this game, they're thinking about it, they take an action and then they leave it. It becomes a separate place you go to for this activity and feeling. That's why it looks like a game. Maybe it is a game."

Right now, Kind Words still has a fairly small community of about 3000 users, of which Scott says he has had to ban around 12 total. The game has a report function, and all reports go straight to Scott's inbox, where he then deals with them personally by either issuing warnings or bans, including personalized notes explaining why the person has been banned. Most bans so far have been issued to people who simply showed up to troll, while warnings are reserved more for misunderstandings, such as (per Scott's example) someone who posted a link to a Discord community they made to talk about the game.

"No one can ever get that satisfaction of having upset someone if that's what they're trying to do"

"Some people don't realize they're talking to real people, so I've given out a fair number of warnings for that," he says. "Some people make a request wanting to be able to reply to someone. If someone writes them a nice letter, they want to reply and maybe start a conversation like a pen pal. But it's central to the design that you can't. The flow of conversation goes: request, reply, and then a sticker is 'thanks.' No other words. In this way, no troll, no insult ever gets a rise from a victim. No one can ever get that satisfaction of having upset someone if that's what they're trying to do."

"My moderation queue this morning was about 20 emails about three issues. There are a lot of eyeballs on it who are trying to keep the game nice."

Right now, Kind Words is only available through the past month's Humble Bundle, though a Steam launch is planned for September. At its Humble launch, the game is effectively done, though Scott says he's working on improved moderation tools before the Steam release expands its audience. That includes an auto-moderator that can suspend posts that receive too many reports until Scott can look them over, as well as extra features to cut what Scott refers to as "noise" from well-meaning people who misunderstand the point of the game.

"I intend to do more messaging about 'channeling' people," he says. "Some of the noise we get is people who, because they can't say 'thank you' to people directly, they'll make a public request to say, 'Hey whoever wrote me this letter about that, thanks so much!' or 'Here's an inspirational quote for everybody.' It's this wellspring of positivity, but it's also noise and dragging the game down. Most of the work being done between now and the Steam launch is about making it easier for people to interact with the game in a way that's healthy and requires less moderation."

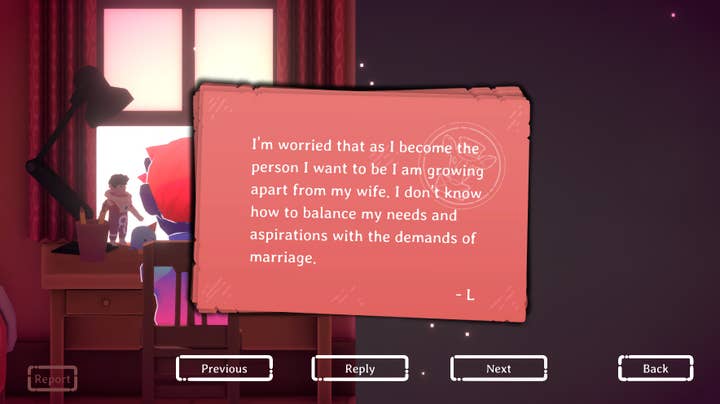

Moderation in a game like Kind Words is far more than just dealing with trolls and people posting links or making mistakes about the purpose of requests. When writing requests, the game invites players to be vulnerable and to share their worries, fears, and feelings. That means that while a number of messages contain expected concerns over things like break-ups, career struggles, and family arguments, some enter into much darker territory.

"Most everywhere in the game you're only one click away from seeing a suicide hotline phone number and links to various other mental health resources"

"One of the people I had to ban, their requests were so full of hurt that people warned me about them and said, 'Please help this person find attention, they're really hurt,'" Scott says. "And their responses to other people were so mean I was getting reports saying, 'You need to ban this person, they're hurting others.' That was weird and tricky. I banned them, but I wrote a very gentle ban, something like, 'I can tell you're hurting, here's links to resources, but also you're hurting other people in this community so I have to ask you not to be here.' I keep finding weird and unexpected angles on people's pain.

"There have been a number of suicide notes. People reported them immediately. Most everywhere in the game you're only one click away from seeing a suicide hotline phone number and links to various other mental health resources, because we anticipated that this would be a magnet for this extent of feelings. When someone posts one of those, I make the in-game deer character pop up and send them a personal note saying, 'It seems like you're having a hard time, here are these links; here is this phone number.'"

The game's small community is by and large doing its best for one another. Scott says that when something like a suicide note or concerning request appears, people rush to report it with good intentions, asking him to do something to help. And reports or not, players genuinely seem to be trying to help one another, even when there isn't much practical help or advice to be given.

"I keep finding weird and unexpected angles on people's pain"

"[Players] are bringing very specific personal situations, and walking away with other people's reflections on those. A lot of them are general, amateur advice, the best most of us can do without years of training as a therapist or something. I think people are taking away that in their specific situation that they are at least not alone, or they're being validated that yeah, you have a right to be upset about this. Eight people immediately wrote you back and said, 'That's rough.' I hope that helps people."

As the sole moderator of a game that's effectively a constant and growing flow of messages of hurt and sadness seeking comfort and understanding, I ask Scott how he personally was being affected. He pauses for some time before responding.

"The game has this limited bank of communication," he says. "I'm never going to see pictures, there's no video or voice, and there's not much follow-up. I don't want to distance myself from this situation. But the design of the game will keep my relationship with these kinds of posts more structured and as distant as I need it to be to not constantly be dragged down by it.

"But we're still less than a week into this game coming out [at the time of the interview]. There's a lot about my relationship with my own game that I don't know yet."

Even if some of the messages are hard to read, Scott says that making something like Kind Words was important for both himself and Guatieri (who has continued to work with him since Elegy) as a response to the world around them, and the negative ways they have seen things change in recent years.

"Luigi and I are both political people and we're both stressed out about what's going on around the world and particularly in America," he says. "It takes up a lot of our mindshare and a lot of our complaining. We live in Boston, and every now and then there are marches and we'll go march in the streets, but it's not enough. And while this is not a game about American politics, it's in some way a reaction of ours to how much cruelty and indifference toward each other that seems to be surfacing. It was important to us to work on something that adds what we want to the world."