Metal Gear Solid was ahead of its time

Why I Love: Sumo Digital designer Emily Knox explores how the PSone classic shaped and inspired her childhood self

Why I Love is a series of guest editorials on GamesIndustry.biz intended to showcase the ways in which game developers appreciate each other's work. This edition was contributed by Emily Knox, level designer at Sumo Digital and formerly at CCP on EVE: Valkyrie.

It was 1999, I was nine years old. I would never have been able to articulate at the time (although I'm sure I did try) why I loved Metal Gear Solid so much.

After purchasing issue 42 of the Official UK Playstation Magazine and playing the accompanying Metal Gear Solid demo from start to finish countless times, I bought Metal Gear Solid. I also bought every magazine I could find with Metal Gear Solid on the cover. As an adult, I can now look back and say with confidence that I wasn't enjoying this game solely on the traits of being an impressionable--perhaps easily entertained--child. There were plenty of sub-par video games I loved to bits for these reasons alone, but Metal Gear Solid earned its place in my imagination for years to come because it was truly ground-breaking.

Stealth gameplay

First off, I think it's always valuable to give a brief overview of what a game is no matter how renowned we believe it to be. Metal Gear Solid was coined in some magazines at the time as a "stealth 'em up." Your objective is to infiltrate a guarded base, and while your character has lethal capabilities, greater success is found by remaining unseen, primarily by avoiding patrolling guards and security cameras.

Metal Gear Solid paved the way with functionality that lends itself to the stealth style of play. The unusual top-down camera angle allows you to observe the movement patterns of nearby enemies, and the Soliton Radar, a small mini-map in the top right corner, builds on this information with clearly defined visuals to display walls for cover and enemy line of sight in the form of a small cone of vision.

With these ingredients alone, you have everything needed to progress through an area without alerting guards, and beginning with no weapons, it is in this fashion you must initially proceed. These mechanics were showcased in the playable demo, along with additional nuances, such as the sound of walking through a puddle which can be heard by nearby guards. It sounds quaint now, but only because for the next 20 years other games followed in these footsteps.

Then there's your ability to 'hug' the wall, now a staple ingredient in third-person shooters and stealth games alike. Pressing yourself against a wall edge causes the camera to swing down, giving a dramatic straight-ahead view, with our hero, Solid Snake offset to one side. It's a brilliant way to 'peep' down a corridor while remaining unseen.

Cast your memory back to the player's first few actions, in both the playable demo and the final game. After crawling under an obstacle, the most likely course of action is to run straight ahead. Conveniently, this leads the player into a wall edge, which results in the wall hug, the camera swings down to show a guard walking towards the player, while Snake remains hidden out of the guard's sight. We can see what's going on, while remaining unseen. The beauty is that this capability isn't ever explained; we're simply led into this wonderful mechanic, which went on to become a convention across genres.

Cutscenes & Codec

The series has gone on to be somewhat berated for lengthy cutscenes, but for those of us who are hooked in, they are an indulgence. This was one of the earliest games where we saw the same characters we controlled during game play become animated and voiced in a cutscene, while the norm was often pre-rendered visuals. In Metal Gear Solid: The Twin Snakes, a 2004 remake on the GameCube, one of the most notable changes is that the cutscenes became much more elaborate, particularly in terms of action and character animation. By now it could be rose-tinted nostalgia, but I still feel there's an immersive simplicity to the original - there's virtually nothing Snake does in a cutscene that the player can't do in-game.

"The Codec gave players all the time they desire to scrape more information out of available characters by calling them; it was a tantalising drip-feed of knowledge"

The perfect example of this is after breaking into the cell where DARPA chief Donald Anderson is being held. During this cutscene as the characters are talking, a guard outside looks in through the cell observation window, Snake hugs the door aside the window, evading the guard's view. At this same moment in The Twin Snakes, Snake instead performs a ceiling cling, an impossible feat for the player, which breaks the game's immersion somewhat.

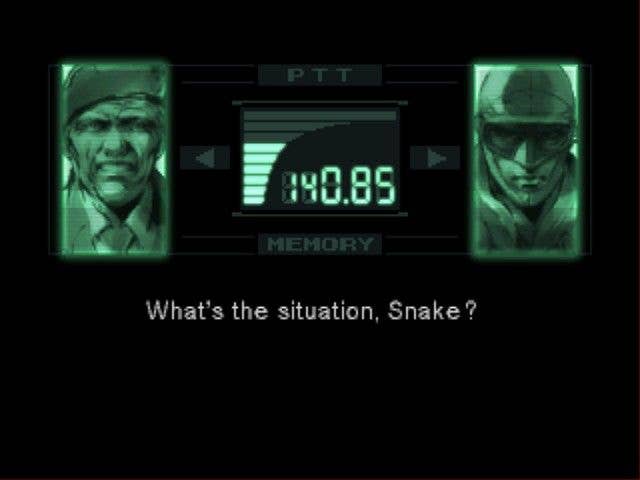

Outside of conventional cutscenes, we also had the Codec. (Think of making a phone call with a headset, and that's all there is to it.) The Codec gave players all the time they desire to scrape more information out of available characters by calling them; it was a tantalising drip-feed of knowledge. Every time there was a story development, I would ring each character and see what they had to say. For this I was rewarded with titbits of backstory, perhaps a comical moment, even useful game play tips. Ring Master Miller while you're crawling through an air duct and he'll advise that you can follow the mice to reach the exit. Delivering information in this style pulls the player further into the world than the more commonly used loading screen tips we see today.

Using the Codec is conveyed with a simple call screen; it shows the number you're calling, the portraits of characters in the call, and subtitles. With a masterful soundtrack to build tension, create drama or evoke sadness, a huge amount of story was told in this way and to great effect. For Metal Gear fans, off the top of my head: the elevator scene, Master Miller's reveal, and Naomi Hunter's past are wonderfully memorable moments each encapsulated in this primitive format.

Characters

The characters of Metal Gear Solid are wonderful: villainous (sometimes comically so, and that's no bad thing), deceptive, conniving, skilled, and almost always better informed than Snake. Roles in the story were dished out to male and female characters alike. We had Nastasha Romanenko, Mei Ling, Dr Naomi Hunter, Sniper Wolf, and my personal favourite, Meryl Silverburgh, the somewhat naïve ginger tomboy and combat rookie. As a redhead and, at the time, an overly proud tomboy myself, a few seemingly inconsequential statements her character made really spoke to me.

"I don't use make-up the way other women do, I hardly ever look at myself in the mirror. I've always despised that kind of woman."

It may be a bit aggressive, but her goals are bigger than vanity, vanity and appearance being sold to us as critical aspects of being female, especially when we are young. And as childish as it sounds, I clung onto some of those words throughout my teenage life.

"To this day the players, press, and developers of video games continue to verbally wrestle over the inclusion of female characters in games, their roles and how they are portrayed, but Metal Gear Solid knocked it out the park all those years ago"

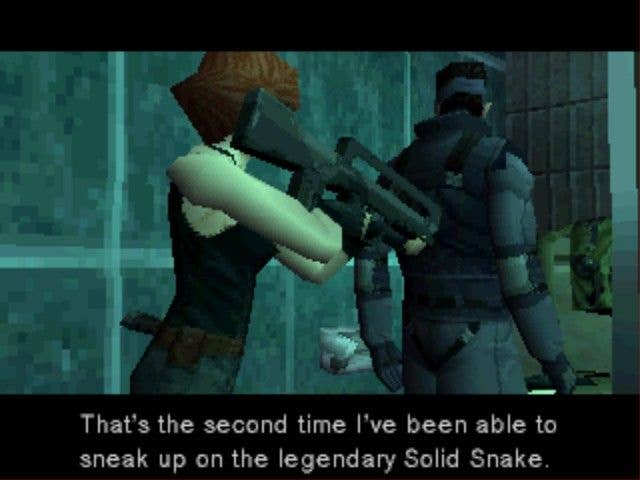

Another perhaps insignificant moment I appreciated was Snake noticing that Meryl uses a Desert Eagle. He opines, "Isn't that gun a little big for a girl?" I still think about this one today because it's a phrase at least one man has said to me about every motorcycle I have owned. Meryl's response? "I'm more comfortable with it than I am with a bra."

To this day the players, press, and developers of video games continue to verbally wrestle over the inclusion of female characters in games, their roles and how they are portrayed, but Metal Gear Solid knocked it out the park all those years ago. Regretfully, women of the series would go on to have less clothes to wear and fewer words to say. For me this hasn't damped the impact of the earlier instalments, but instead further illustrates how brilliant they were.

On top of its technical and artistic achievements, Metal Gear Solid broke the fourth wall in creative ways that completely evaded me as a child, throughout my multiple playthroughs. These were a wonder to discover in later years, and I can only imagine the "eureka!" moments people experienced unearthing them independently.

At one point to progress the story, Snake is instructed to call Meryl on the Codec. He doesn't know the frequency to dial, but you are told it's written on the back of the CD case in Snake's item inventory. As mentioned previously, I never figured this out myself - the number is on the back of the actual Metal Gear Solid CD case. Embarrassingly my only discovery at the time was that if you waited long enough, Meryl's frequency would eventually just appear in your contact list.

There's also Psycho Mantis, a boss you must fight who can read your mind. The trick to this one is to unplug your controller from port 1 and insert it into port 2. As you may have guessed by now I didn't figure this out either and found this fight rather challenging and confusing.

To my knowledge, no other game has undertaken such inventive endeavours with the use of system features, no other game that is other than later instalments in the Metal Gear Solid series, and although I started to have my wits about me by that point, I still had to lookup how to defeat The Sorrow.

Thank you to all the developers and voice acting talent behind Metal Gear Solid, for entertaining, challenging, and inspiring me.

Upcoming Why I Love columns:

- Tuesday, October 9 - Perfectly Paranormal's Ozan Drøsdal on Worms: Armageddon

- Tuesday, October 23 - Sumo Digital's Jamie Smith on Diddy Kong Racing

Developers interested in contributing their own Why I Love column are encouraged to reach out to us at news@gamesindustry.biz.