Rocket League refueling for year four

DLC: The difference between esports and games-as-a-service, blurring lines between players and consultants, 2K's Switch stance, and God of War's redemption

Rocket League's new commissioner

Rocket League is rolling out a new progression update this week that eliminates the level cap and flattens the amount of experience needed for players to gain levels. It's the first big update for the title during the tenure of recently appointed game director Scott Rudi. I spoke with Rudi at E3 about what it's like dropping into an established esport in the third year and making changes, and how that compares to the way traditional sports seem loathe to change anything too substantially.

"For a lot of those sports, it's because they're addressing an issue," Rudi said. "Like, say, the NFL, there are too many concussions, so we gotta look at how we do things and such. You have to balance that. You have to keep the purity of the game but you also have to think about those players. Luckily in our sport, nobody gets actually hurt like that, but you have to keep an eye on it."

Another fortunate break for Rudi that makes changes a bit simpler to deal with is that unlike so many games, Rocket League has no performance progression. All the levels and experience points do is show others how much someone has played the game and help unlock customization parts.

"We just have a very level playing field and it comes down to skill and teamwork as to whether you're going to be winning or not. So we don't have a lot to be fixing all the time, and it really comes down to what we want to add outside the core experience, or fixing minor things like server health or stability."

A static core experience is somewhat fundamental for traditional sports, but it's not exactly a selling point for games-as-a-service these days, which thrive on their ability to reinvent themselves for players over the course of months and years. With that in mind, we asked Rudi about whether he considers Rocket League more of an esport or a game-as-a-service.

"It's both," he said. "The things we do that make it a better game-as-a-service also benefits it as an esport. That's rare. I've been in situations with other games in other places where you had to make a choice: Is this good for spectating or is it good for the core gameplay? The core gameplay for Rocket League lends itself very well to esports, so the only decisions we're really making are what we want to add to the spectating experience, or the shoutcasting experience, or how we keep the game fresh for players, which we would have to do anyway. I just feel lucky I don't have to making Sophie's Choices about benefitting this or that, because it's usually both."

Penny For Your Thoughts?

While visiting Ubisoft Montreal for the Ubisoft Developer Conference earlier this year, I heard a lot about the team's live ops efforts for games like For Honor and Rainbow 6: Siege. Unsurprisingly, all the developers spoke about how essential the players were to their efforts. The For Honor team in particular has top players give early feedback on new content and make regular visits to the studio to discuss the issue with developers.

I don't want to pick on Ubisoft specifically here, because they aren't the only publisher I've heard touting such player feedback programs, but given the players' specialized knowledge, the significant time and travel commitment of such studio visits, and how crucial the developers claim they are to the process, I wondered why they aren't paid as consultants. Clearly they're providing great value with their feedback above and beyond what they bring to each game's competitive scene; surely that's worth compensation of some kind?

When I asked a few of the publisher's live services executives about why they aren't doing this, I was told, "It changes the relationship. If you're a player and you're engaged and you want to participate with the game you enjoy playing... And it's not necessarily an every month thing, or an every season thing. On Siege, we try to rotate [players]. And we do it with the pro players, so as a definition I guess they are getting paid. It's their job. But to me, I believe there's a difference. If you do something because you enjoy it and you want to be part of something as a one-time thing, or if you decide that you're a consultant and you join the game industry."

A customer's passion for a game, a brand, or a storefront is not so much a sign of a job well done as a signal they could be put to further use

Another executive said they "need to be fair to other players," adding, "If it was a consultancy or job, we could not be proving it was a fair approach, taking everybody's feedback. Yes, we are also having this feedback, but those are indicators as data--it's still very much the creative vision that is at the heart of the game."

I don't think they expected the question, and I can't say I was impressed by the answer. Paying for advance feedback on games is something of an industry standard. There's no shortage of ex-journos paying some bills by providing mock reviews for games and there are plenty of market research focus groups that help shape titles and marketing. It seems odd that these lines of feedback are considered worth paying for, but the people fueling the competitive gaming scene around a title (and in turn, its prospects at establishing itself as a lucrative esport), are left with little more than a plane ticket.

This seems to be another instance where the industry conventional wisdom has settled on, "Why pay for something when people will do it for free?" From Steam translations to Steam curation to Xbox community management, a customer's passion for a game, a brand, or a storefront is not so much a sign of a job well done as a signal they could be put to further use. Is it not enough that this passion causes them to buy and play the games constantly, to create the communities on which these games thrive, and in cases of everything from Little Big Planet to Super Mario Maker to Worlds Adrift, to actually create the games themselves?

These are the people you most want in your community, yet you risk burning up their good will by not only having them do such valuable work for free, but making your business reliant on that. Even if these fans seem eager to play a part in the creation of their favorite game, that suggests they feel a level of investment and ownership in the game that the company has no intention of actually delivering to them. The practice is short-sighted at best, exploitative at worst, and something game developers would be wise to wean themselves off sooner rather than later.

2K flips the Switch

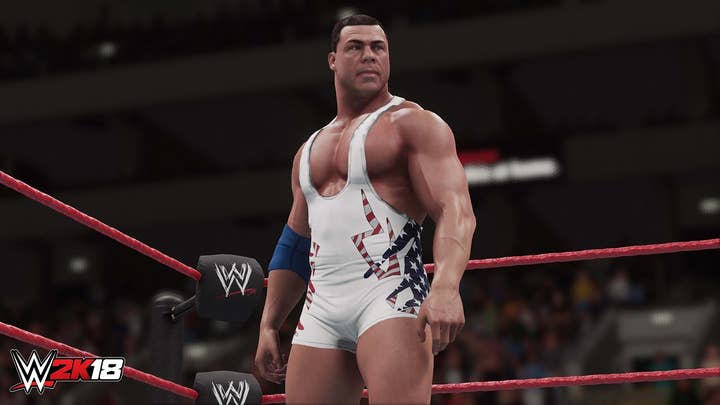

When I spoke with 2K president David Ismailer at E3, I asked him about how the publisher's first forays on the Switch, NBA 2K18 and WWE 2K18 had done.

"We're really happy with our performance on NBA, and WWE. I think we are going to be continuing supporters of the Switch platform. A lot of the developers are huge fanboys of the Switch platform, so they really love developing for [it].

There was a noticeable pause before he added WWE in that first sentence, and for understandable reasons. The game's Metacritic average of 35 was barely half that of the other versions of the game, and its technical issues were well-documented. A month later, 2K confirmed that WWE 2K19 would skip the Switch, explaining, "2K is focused on making the best possible experience for WWE 2K fans and will continue evaluating all opportunities to deliver the franchise across additional platforms."

One thing that didn't hold the Switch version of WWE 2K18 back was the game's requirement that even players of the cartridge version have a microSD card to hold a mandatory 32GB download. NBA 2K18 carried the same storage requirement, as have a number of other AAA games on the system. While such a mandate would have been a deal-breaker for many games just a generation ago, Ismailer said 2K hasn't seen evidence of it hurting sales so far.

"I don't believe it's an issue," he said. "Our goal is to deliver the exact same experience. We don't want to create a different and bifurcated experience for the Switch platform. In order to accomplish that goal--our games are very big--that was the requirement. If we wanted to deliver a different experience, or I would say a sub-standard experience... But when we initially started development on the Switch, the goal was to deliver the same experience you have on [other] consoles."

Bad Reputation

I interviewed a number of voice actors recently about how developers can get the best performances out of them. While most of the people I spoke with were video game veterans, Danielle Bisutti had only worked on one gaming project, playing the part of Freya in this year's PS4 hit God of War. When asked if working in games was something she'd consider doing again, Bisutti gave an enthusiastic yes.

"A lot of these games can be super violent in a very gratuitous way, or a bit misogynistic with their portrayal of women..."

Danielle Bisutti

"Obviously the bar has been set super high with God of War, but if the narrative was right and I felt like the character was written with a lot of integrity, I would absolutely be open to working on another video game with another group entirely," she said. "A lot of these games can be super violent in a very gratuitous way, or a bit misogynistic with their portrayal of women, and I happened to hit the jackpot with Freya. She's this warrior goddess who's a mother and a friend. She does magic, and she's kind, and she's truthful. And there's really nothing sexualized about her. Not that I have an issue with sexuality, but I really appreciated that they allowed for a different archetype of woman to be represented in their game.

"If it was a game that was very violent for being violent's sake, or very sexualized just to get a rise out of people... Even if it was a movie or a TV show, I'm not interested. But I am interested if that violence and sexuality is actually grounded to a narrative where it's important for the story to move forward."

It was an interesting answer because the type of game she described as not wanting to work on was essentially the type of game the God of War series was known for until this latest reboot. You might wonder why Bisutti would sign on for this role in light of that, but as mentioned in the story linked above, she wasn't told what the game was until after she had been hired. So if she had known what the project was and been able to play the original games in preparation for the audition and recording, would she still have gone through with it?

"I don't know," she said. "That's a good question."