Inkle starts a bold new chapter with Heaven's Vault

The British studio is taking a step beyond the interactive fiction of 80 Days into a fully realised visual world

With 80 Days, Inkle accomplished that rarest of feats: a premium mobile game that can legitimately be called a hit. Released in the same year as ustwo's Monument Valley, the British studio's narrative adventure was another game that suggested it was still possible to charge money for a great product on the app stores. Whether you see that as a sound strategy is another matter, but there's no doubt that it worked very well for Inkle.

The success of 80 Days has allowed Inkle to be far more ambitious with its next game, Heaven's Vault, which is entirely funded by the revenue from the studio's back-catalogue - with 80 Days the single most important contributor.

"It's lovely to be beholden to nobody," says Jon Ingold, Inkle's narrative director, who co-founded the studio with art director Joseph Humfrey in 2011. "Sometimes, in your darker hours, you wake up and think, 'If we just hadn't made another game, how much money would we have?'"

"To make another game in the mould of 80 Days? I don't know what we'd be trying to prove"

More than any other game in Inkle's portfolio - which also includes the Sorcery series - with Heaven's Vault the money is up there on the screen. According to Ingold, the studio had iterated "quite carefully" through the four chapters of Sorcery on to the more visually rich 80 Days, but it soon became clear that innovation would require its next game to be based on more than just text.

"In 80 Days you could get away with everything, because you can just write it down," Ingold says. "From the point of view of the challenge, 80 Days proved that interactive fiction could be accessible, immersive, engaging and interesting; all of the things that people said it couldn't be.

"But to make another game in that mould? I don't know what we'd be trying to prove. The thing that we're trying to prove now is, 'You know adventure games? They can be fluid, they can make sure you never get stuck, they can be immersive, they can tell great narratives without that moment where you go, 'I've got to do what with the goat?'"

"Telltale are doing it really well," Humfrey adds. "They've managed to take it so far based on this frame that hasn't really changed very much. We get itchy feet about not changing the formula... But we're not going, 'How can we change the adventure game?' If anything, we're taking what we've done so far and putting another brick on top."

While Heaven's Vault's fully realised 3D world may be entirely new for an Inkle game, it is more of a logical evolution of the studio's previous work than it first appears. Fundamentally, it adheres to the same idea that has been at the core of Inkle since it was founded: as Ingold puts it, "games shouldn't be set up as a series of vending machines that you go and throw your coins into"; a standard pattern for adventure games, "because it's easy to author."

Indeed, Heaven's Vault is built on a new version of "Ink", the script engine that allowed 80 Days to feel so open and yet so reactive and precise at the same time. This time, however, Ink has been modified so instead of generating prose based on the player's myriad different choices and experiences, it now produces what Humfrey describes as, "an interactive film script, which is then read by the game and presented visually."

"We're tracking almost everything the player ever does: what they know about things, what they think about things"

"The script that's generated uses a lot of the same principles that the scripts do in 80 Days and Sorcery," Ingold adds. "They're dynamic, they track character relationships, if you talk to a character they're not going to repeat themselves. If you missed what they said then you missed it. If you annoyed them and they went off in a huff, then that's what they did and you're going to have to live with it.

"We're tracking almost everything the player ever does: what they know about things, what they think about things, what other characters in the world know about things. The dialogue then uses that information to make sure it's always on point. Pretty much every line of dialogue is doing that."

To use a somewhat pedestrian example, if the player is seeing an important building for the first time, the character will acknowledge it with surprise or curiosity. If they are returning, it will be acknowledged as familiar. If they are returning with any of a dozen pertinent pieces of knowledge about the building - which can be collected in any possible order - the resulting dialogue will be tailored to the exact combination. This "ability to model knowledge fast" is what makes this version of Ink distinct from the one that powered 80 Days.

"You write a little bit of content here and a little bit of content here and you just track a lot of information," Ingold says, "We're doing that all the time, throughout the entire game. I think there's something like 1,500 knowledge states across the script so far."

And the player can move between those knowledge states with absolute freedom - quite different to the "well defined paths" of 80 Days. The protagonist of Heaven's Vault is an archaeologist, but Inkle didn't want to make a game about, "scrubbing around with toothbrushes." It also moved beyond an initial conception of archaeologists as akin to detectives, because a detective is trying to uncover a knowable truth. Archaeologists, Humfrey explains, "can never actually be sure they've got it right."

"It is a massively ambitious thing to do with eight people"

"You've got nothing but your theory, which is coloured by your experiences," he says. "That led us to the idea of a very ambiguous collection of information. This is my current theory. This is what I think I know, but there's clearly holes in it. There's always holes. You can never fill it in."

In Heaven's Vault the mystery is a place, the Nebula, which contains a series of locations that players can explore in any order. As they discover new information it appears on a timeline, which stretches from millennia in the past to actions taken just a few moments before.

"That sense of the past being, however close you get to it, still a foreign country, that's so good," Ingold adds. "Partly because it helped us to design our mechanics and our UI, but also because it feeds right back into the narrative in the first place. That's what makes archaeology special."

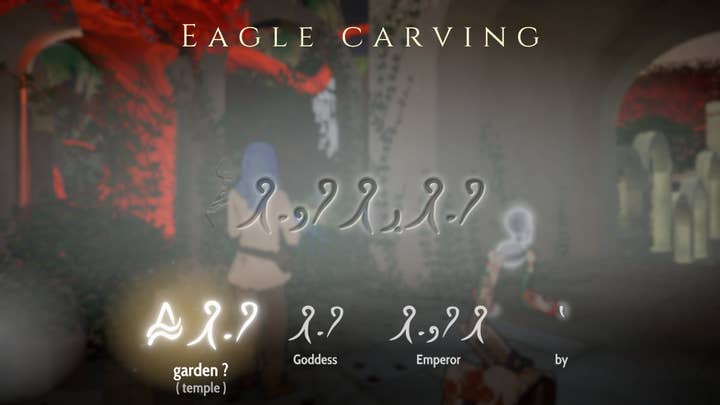

It is also where the clearest through-line to Inkle's other work can be found. Where Sorcery and 80 Days were explicitly told through words, the mysteries of the Nebula can only be solved by translating glyphs that make up its native tongue. The remnants of the Nebula's dead language are still visible in all of the game's locations, but players will have to translate with only the help of the environment, or seeing glyphs used in combination. And as they piece together the timeline of what happened, they might come to realise that their original translations were entirely wrong.

"You won't know those meanings immediately, so you might have to guess, and you might get it wrong," Humfrey says. "And we won't necessarily tell you immediately if you are right."

"There is a right answer, but we're not going to tell you if you've got the right answer," Ingold says, adding that Heaven's Vault's "translation mechanic" isn't a puzzle, because puzzles communicate a clear solution. "There isn't necessarily a way of solving it. There are lots of reasons you might have for choosing your translation: the location, the tone of the environment, the object it has been inscribed on... The idea that we can make something which has the affordances, and the engagement, and the satisfaction of a puzzle mechanic, but it's narratively absolutely on point. That's brilliant.

"We've quadrupled in size from what we were on 80 Days. And it's mostly artists"

"You can get to the end [of Heaven's Vault] without having full knowledge of the language. You can get to the end without having a full understanding of the history of the Nebula. You can get to the end with contradictory ideas about what the history of the Nebula might be."

And these feats of fluid, ambiguous narrative are depicted with more visual flair than any Inkle release to date. Heaven's Fault has 3D environments, a distinctive animated style for its 2D characters, and a beguiling sense of style and place. Where 80 Days felt like a celebration of words, Heaven's Vault is in rapture to both language and image at once. Inkle's team had to expand considerably to make it possible, Humfrey points out - it's one thing to just describe a world of delightful steampunk contraptions, and quite another to make each object real and coherent with the world of the Nebula.

"We've quadrupled in size from what we were on 80 Days," Humfrey laughs, acknowledging the grandiosity of applying the term 'quadrupled' to a jump from a few people to a handful. "And it's mostly artists. The more that we've done, the more we've realised that, to get the game to meet the ambition we have for it, we need to do more with artistically."

"It is a massively ambitious thing to do with eight people," Ingold adds, of bringing Heaven's Vault's dozen or so locations to life. "But because we found ways to do it with eight people - things like using the 2D art [for the characters], rather than having 3D character animation and mo-cap - we can collaborate incredibly efficiently.

"In 80 Days you could just write a scene and you knew it would work... We got nothing for free on this one"

"If Laura [Dilloway, senior artist] and I want to argue about what materials something is made of, we can and it's done. There's no friction there whatsoever, no interference with production. We have a level of flexibility that you just can't find in a studio of even 20 people, and you certainly won't get in a studio of 200 people. That's incredibly exciting."

After a long period spent working out the structure that would allow Heaven's Vault's narrative to work, Inkle reached the point where "everything was just working" at the end of 2017. The myriad systems that let players roam the Nebula freely, learn its secrets in any order, and revisit old locations to offer new interpretations, were all functioning to speaking to each other. "It's primarily just content at this point," Humfrey says. "We've got a lot of space to build up."

"And the other thing is rigging. Once you've built a 3D world you have to put the cameras in the right place, and the props in the right place, and you have to test absolutely everything because 3D games break all the time. In 80 Days you could just write a scene and you knew it would work - mostly - whereas here nothing ever works. It's not even polish at that point; it's just getting it to work.

"We got nothing for free on this one. It doesn't work like a normal 3D adventure game. It doesn't use jumping or platforms, there's no one linear route, there's no grappling hook mechanic, there's no shooting. If you want to give the player something to do you'd better think of something interesting, because you can't just chuck an enemy at them. Fortunately, we seem to be cresting that hill."

When asked for a possible release date, Ingold and Humfrey share a reluctant glance. It's clear that Inkle is willing to keep working until Heaven's Vault matches its vision for the game; not only because it has funded the project independently and intends to self-publish - Ingold concedes that "it is pretty terrifying out there" for indie games right now - but also because this will be the first Inkle game to launch on console, specifically PlayStation 4.

"Our conversations with the marketing department at Sony have been really good, actually," Ingold says. "We say we've got this story-based, combat-free, puzzle-driven game. We tend to describe it as Firewatch meets the The Witness via Stargate, which is definitely not a good description of the game, but it'll do for a one-liner."

"Like every indie studio, we need all of the allies we can find."