Welcome to the New Era: Games as Media

SuperData's Joost van Dreunen sees games, like other entertainment, being more highly targeted by advertisers

In 2013, King triumphantly announced that it would remove all ads from Candy Crush. The game had become a huge financial success using micro-transactions and no longer needed the comparatively marginal income from interstitials and banner ads. Instead, the firm doubled its "focus around delivering an uninterrupted entertainment experience." Even if it did not abandon its free-to-play revenue strategy, to many it was a step in the right direction that mobile game makers were reconsidering the design implications of their monetization approach.

But the world has changed considerably since then. Game companies are soon going to generate a growing amount of revenue from advertising... again.

For one, the mobile games market has continued to grow at double digit rates since then: from $21 billion in 2013 to a forecasted $38 billion by the end of this year. Today, the mobile gaming audience is split between offerings from more and better-funded stronger competitors. In this ecosystem, marketing has started to play a more prominent role. It now resembles the traditional game publishing business more closely, with a reliance on high production values and a growing marketing spend: The mobile games market is maturing.

Second, after a consistent growth rate in recent years, adding new consumers to the overall addressable market is becoming more difficult. Apple and Google compete head-to-head over markets like China and India, where they each seek to capture the largest possible consumer audience. But these markets present challenges for publishers that seek to monetize using micro-transactions. The percentage of players who convert to spending in China, for instance, is about 3.4% compared to a worldwide average of 4.2% (August, 2016). For a market that size, that is a lot of people not spending any money.

"This popularisation of interactive entertainment has vast implications for the way game companies make a living"

But perhaps the biggest change since King abandoned ads has been its complete turn-around with its current exploration of how to best use ads in its games. Where previously small and medium-sized developers would generate up to 40% of revenue from advertising, big publishers enjoyed the privilege of being able to disregard this type of income. But we are now seeing the beginning of a period in which even top mobile game makers are actively experimenting with this generally eschewed revenue model.

More broadly, it is a sign of things to come as the games industry shifts again in the next few years. Since the introduction of the smartphone in 2007, the image of an affluent mobile gamer has steadily eroded. Instead it has become more akin to that of a regular person just playing a game with the occasional commercial or ad, much like an average television viewer or someone reading those free newspapers you get on the subway. This popularisation of interactive entertainment has vast implications for the way game companies make a living.

Making money from games

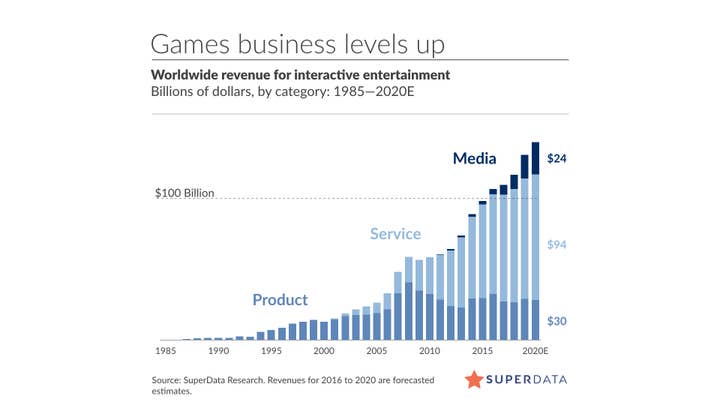

Succinctly, the games industry has gone through three different time periods, each characterized by different distribution models and revenue strategies. For most of the industry's history game companies have generated revenue by selling boxed CD-ROMs and cartridges through retail. Games were sold as a product, and many continue the trend. Due to the persistent increase in development costs, this model ultimately became a strongly hit-driven one, resulting in a relatively consolidated industry where only a few publishers, retailers, and platforms controlled the larger part of the market.

The second era followed the widespread adoption of online connectivity and a general digitalization of entertainment. In this context, games are experiences that in some cases don't cost a player anything, at least upfront, and gradually monetize over time. This model stands almost in opposition to its predecessor because it is based on a service model that emulates that of the software industry, allowing for ongoing iterations to a game and obligating publishers to maintain servers, customer services, and regular marketing and sales efforts. Important in this context is that during the time it took for games-as-a-service to become popular among both designers and consumers, lots of new companies entered the market, which, in turn, has become a global one, because it is no longer constrained by the physical boundaries and real-world logistics that characterize retail distribution.

And finally we are now coming up on the period of games as media. This offers a two-sided business model in which game publishers both directly extract revenue from consumers and leverage their aggregate audience to also earn revenue from brands and advertisers. With the explosive growth in both the size of the addressable market for interactive entertainment and the diversity of its audience, the two-sided business model has gradually made its way back into the minds of senior executives at game companies.

So why now?

The companies that dominate the games industry today are different from the ones before. Certainly, Sony and Microsoft still command authority. But with mobile games at $38 billion annually, which puts it ahead of both the digital console ($6 billion) and PC market ($33 billion), there are now new industry leaders. Companies like Apple, Google, and Facebook look to control audiences and find smart ways to monetize them. According to its earnings reports, Facebook earns $11.26 annually per monthly active user, all of it indirect revenue from advertisers, and making it highly unlikely that its ultimate offering in virtual reality will be ad-free. The financial interests of the companies that have come to dominate the industry landscape will change the way consumers pay for their games.

For King, the time has come to identify additional revenue streams: over the last two years the user base for Candy Crush Saga, its biggest mobile title, has steadily declined from 245 million monthly actives in early 2014 to around 166 million today. The percentage of people who spend money, however, has dropped by half, from 4% to 2%, and consequently revenues have fallen from well over $120 million a month in early 2015 to just over $53 million today, a cool $800 million that the company is not making annually. Following its acquisition, King has obviously undergone a process of organizational optimization as part of its integration into the larger Activision empire. But now that that's done, the publisher is exploring additional revenue streams with King running tests on ad revenue in one of its minor titles AlphaBetty Saga.

More broadly speaking, Activision's consistent hiring of media executives for its eSports division suggests that they are trying to close the gap between advertisers and competitive gaming events. Around $0.77 cents of every dollar generated in eSports come from advertisers. And the longer-term payoff in this category is going to be the increased revenue derived from selling media and broadcasting rights. More so, when looking at gaming video content, a market segment valued at $4.4 billion this year, Activision's titles are consistently among the most popular games on Twitch and other channels.

Will it initially be controversial? Sure. Will game designers balk at the mundanity of integrating ads to their perfect creative vision? Absolutely, and rightly so. Will consumers see it that way? Unlikely.

"Audiences for interactive entertainment have changed and now have a much higher tolerance level for commercial messages in exchange for getting to play for free"

Now that games have reached a scale where hundreds of millions play every day with no intention of spending money, game companies are looking for incremental revenue streams to support the overall effort. Audiences for interactive entertainment have changed and now have a much higher tolerance level for commercial messages in exchange for getting to play for free.

There will be purists who abhor the notion of putting ads into their game. And there will be services that offer premium games inside walled gardens, charging a pricey subscription in exchange for content with high production values. But there will mostly be advertisers and brands desperately looking to connect with audiences who are increasingly abandoning other, more traditional forms of entertainment. Almost irrespective of platform type, games are consistently among the most popular entertainment category. Part of the package with becoming mainstream is that the games industry is now also going to have to make some concessions in pursuit of its newfound revenue potential.

Of course, no publisher worth its salt is going to plainly unleash ads and risk alienating its audience. It will likely be a gradual, closely monitored process as game makers find creative ways to strike a compromise between an unfettered vision and consumer-imposed reality. But now that games have become a mainstream form of entertainment, they have the attention of millions of people and, therefore, the attention of advertisers.