Saving APB

How Reloaded productions is rebuilding Realtime Worlds' MMO

In August last year, Realtime Worlds, developer of Crackdown and APB, went into administration.

APB had failed to attract the subscribers necessary to keep the studio afloat, with just 130,000 registered users on the books. Debts were piled high, and job losses were imminent.

Over the course of the next weeks and months the UK industry watched the drama unfold, truth and rumour interwoven predictably densely as the fate of the company's assets and workers was decided.

In many ways, the story defined a sea change in the industry, strangely prescient of tough times ahead: a big studio running an expensive, traditional model project collapses; small studios arise from the ashes and the project is given fresh hope in a switch to free-to-play mechanics.

This timeline of events has been echoed in various forms many times in the 14 months since. The UK's industry fractured as large teams fold and give rise to smaller units interested in agile development and emerging platforms. Smaller budgets, shorter deadlines, less risk.

But the ultimate fate of APB remains unique. Developed as a big-budget online game with a traditional boxed-product, subscription economy, the game is now being transformed by free-to-play specialist GamersFirst, employing an Edinburgh-based team of 23 ex-RTW staff.

When we showed up there were six guys left in the company, who were just being paid by the bankruptcy administrators to maintain something to sell

Bjorn Book Larsson, CTO/COO, GamersFirst

It is, many of the studio's members tell me on a recent visit, the chance to make APB the game it could, and should, have been.

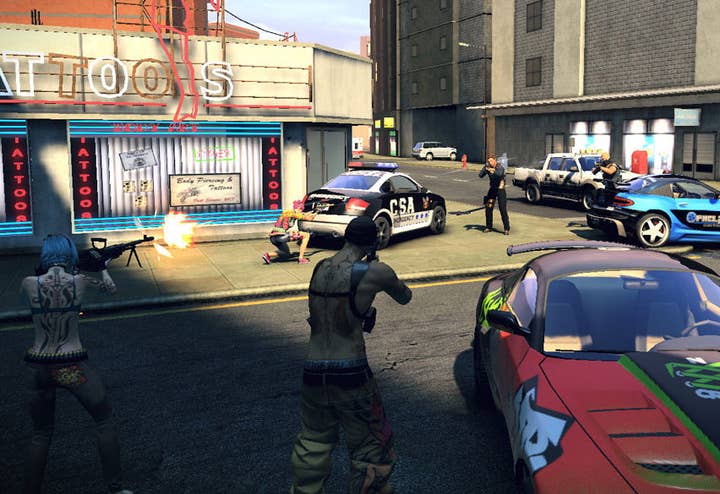

When the game first launched, on July 2, 2010, it was met with poor reviews and a barrage of negative feedback from players. Poor driving and shooting models were contrasted with incredible levels of customisation and graphical fidelity. Server-side lag and accusations of player cheating sealed its fate.

When GamersFirst stepped in and acquired the rights there was a lot of work to be done, but it recognised the potential for a profitable game.

"What happened from our side was that I followed a blog by a guy called Luke Halliwell, who was an employee at Realtime Worlds," GamersFirst CTO/COO Bjorn Book Larsson tells me.

"He was talking about everything going wrong in major game development. In large, 300 person teams. Through that we actually realised that the company had gone out of business. It was through his blog. We followed it because we thought it was a really great idea. Who doesn't love GTA Online? That'd be awesome.

"So we flew out to Dundee, brought tech guys from the US, and tried to figure out what was left. When we showed up there were six guys left in the company, who were just being paid by the bankruptcy administrators to maintain something to sell."

Admistrators Begbie Traynor were somewhat unprepared for the attention the collapse of the company attracted, particularly from the specialist press. Fielding journalists' calls about the current stage of the process was a daily task, and the emerging information became muddied and uncertain.

As Larsson suggests, Begbie Traynor were also not particularly experienced in the finer points of maintaining networks of servers holding various branches of iterated development trees.

"The administrators may not have been the most diligent when it comes to software and what it depends on and the components. So from purely a technical side, the takeover was a much bigger headache and nightmare than we had previously anticipated. We thought we'd show up and get the source code and be done, but it wasn't as easy as that. It required quite a bit of reconstruction, finding stuff all over the place."

Essential to the process, he says, was securing key personnel who knew the ins and outs of the game's history.

"We were quite fortunate because we found a few key guys who were former RTW people, like Mike Boniface, who was the former director of IT, and some guys below him, as well as some of the key developer guys. We were able to persuade them to come and work with us, initially as contractors, and then convert to full time and buy in to the whole process.

"At that stage there was also the financial side, which turned out to be pretty complex because there were dependencies on Epic Games and some others for some of the licensing. It was a pretty big, crazy deal. There were press in the UK who reported how much we'd bought the game for [estimated as £1.26 million], but the reality was that it wasn't quite accurate because the deal that we had offered required the administrators to also pay for some licenses, so we ended up paying more than was reported in the past. The real figure was maybe higher by 20-30 per cent.

"Then of course we had to carry the cost of the legal transition and everything else to make it happen. So it ended up not being a cheap deal for us, but obviously a lot cheaper than the initial development. We were very lucky to find Mike and the core development team."