Far Cry 4 already playing with fire

Promo art for Ubisoft's upcoming shooter raises eyebrows, questions about why developers push players' buttons

In the Far Cry games, fire is a wonderful tool. It spreads dynamically, opening up a wealth of creative and strategic possibilities for players to achieve their goals. However, it also gets out of control in a hurry, potentially coming back to hurt the player in sometimes unpredictable ways.

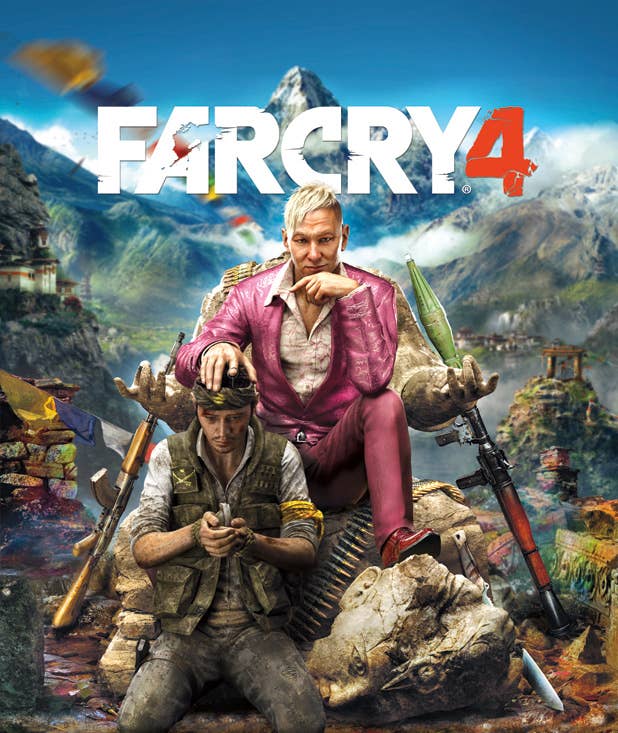

It's an appropriate metaphor for the series' approach to controversial subject matter. Last week, Ubisoft announced the development of Far Cry 4, showing off some key art in the process. The picture depicts a blonde light-skinned man in a shiny pink suit against the backdrop of the Himalayas, smirking as he uses a defaced statue as a throne. His right hand rests on the head of a darker skinned man who is kneeling before him, clutching a grenade with the pin pulled. Though we know very little about the characters depicted, their backgrounds, or their motivations, the art got people talking (and tweeting). Some were concerned about racism. Others were worried about homophobia. Many saw neither. At the same time, details about the game are so scant that it's entirely possible the problematic elements here are properly addressed within the context of the game itself.

"[W]hile we lack the context the actual game would provide, there's no such thing as 'without context.'"

But at the moment, we don't have that context. It's promotional art, so to a certain extent, it's designed to exist out of context, to catch the eye of someone on a store shelf, even if they've never heard of the series before. And while we lack the context the actual game would provide, there's no such thing as "without context." Here, the context we have is that this is a Far Cry game, the latest entry in a series that has been earning a reputation for boldly storming into narrative territory where other games fear to tread (often with good reason).

Like the fire propagation mechanic, this narrative ambition was introduced to the series with Far Cry 2. What had previously been just another shooter (albeit one in a tropical setting more attractive than most) became a series that embedded its stories within thorny issues. Far Cry 2 cast players as a mercenary in a fictitious African country's prolonged civil unrest, using blood diamonds, malaria, and Western imperialism as texture in a story emphasizing the moral vacuum of war. Far Cry 3 took things a step further, with players controlling a spoiled rich white kid on a tropical island vacation who suddenly must deal with nefariously swarthy pirates and intentionally stereotypical natives. And just in case that didn't stir up any controversy, the story also weaves in rape, sex, drugs, and torture. In both cases, some critics and players felt the games offensively trivialized important or tragic subjects.

Given this history, it's not surprising that Far Cry 4 would not universally receive the benefit of the doubt. Much more surprising (to me, at least) is that Ubisoft is continuing down this path with the franchise. Far Cry 3 sold a staggering 9 million units, putting it in the same class of blockbuster as Assassin's Creed (last year's version of which sold 11 million units). However, the publisher's narrative approach to the two games could not be more different.

Assassin's Creed is a fascinating case study for dealing with touchy subjects in AAA video games. It wasn't long after the US invaded Afghanistan and Iraq that work on the first Assassin's Creed started. You know, the one set in the middle of a holy war between Christians and Muslims. Assassin's Creed II had players attempt to assassinate the pope. Assassin's Creed III put players in control of a Native American protagonist during the Revolutionary War. Assassin's Creed IV: Freedom Cry saw the gamification of emancipation.

The Assassin's Creed franchise draws some criticism from time to time for its handling of these subjects, but the series has rarely found itself at the flashpoint of controversy. Part of the reason for that is the Assassin's Creed developers research their subjects thoroughly. They understand what the concerns surrounding the sensitive topics are, and by virtue of the games' historical settings, they can point to factual evidence of certain people's actions, or common situations of each era.

"[T]he right to explore those subjects should come with a responsibility to do so with care."

When it comes to dealing with controversy, Assassin's Creed is much like its stealthy protagonists are imagined to be: quiet, cautious, and efficient. Far Cry, on the other hand, deals with these topics more like the way Assassin's Creed protagonists behave when I play them: recklessly uncoordinated and endlessly destructive. Even when it's clear Far Cry's developers have put plenty of thought into what they're saying, it's not always clear they've put much thought into what people will hear them saying through their games.

It speaks volumes about how Ubisoft perceives the long-term value of the two series. Assassin's Creed is the company's biggest and most adaptable blockbuster, an annual gaming event based on a premise that can be mined and iterated on endlessly in almost any medium, a recurring revenue stream to be nurtured over time. Far Cry, this key art release suggests, is just another first-person shooter, a brand defined primarily by how hard it works to shock people, perhaps because the company doesn't have faith that it can sell on its other merits. One of them is the kind of project you make a Michael Fassbender film around. The other might be more of an Uwe Boll joint.

I'm not saying that Far Cry should avoid these subjects. I actually love to see games of all sizes attempting to tackle topics and themes often ignored by the industry. But the right to explore those subjects should come with a responsibility to do so with care. These are legitimately painful subjects for many people. If developers want to force players to confront them, they should have a good reason for it that goes beyond pushing people's buttons, exploiting tragedy for shock value and an early preorder campaign. In video games, we don't push buttons for the sake of pushing buttons. We push them to do things.