Publishers Betting On "Fewer, Bigger, Bloodier"

The traditional game industry's growing reliance on violence is marginalizing the medium in short-sighted and self-destructive ways

The gaming industry depends on violence to drive sales more and more every year.

Given the amount of public scrutiny gaming has been under since the Newtown shooting last year, that might be an uncomfortable truth for many in the industry. But it is a truth.

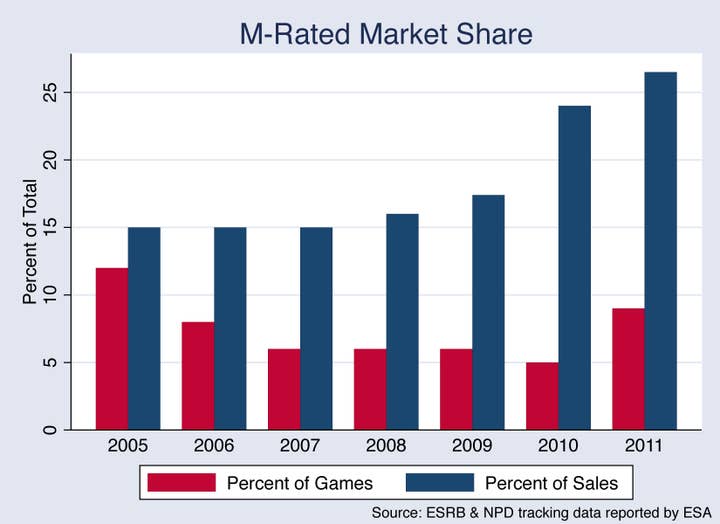

As the graph below makes clear, there's a growing disparity between the number of games that receive an M-for-Mature rating and the amount of US retail software sales they make up. In 2005, 12 percent of the games rated were mature, compared to 15 percent of games sold. But as the generation went on, the gap between those two numbers became a small chasm. In 2011, the M rating was responsible for more than one of every four dollars spent on games, but fewer than one of every 10 new games.

Consider that those sales numbers are in units instead of dollars, and the current M-rated market share is likely even more disproportionate. After all, the platforms least likely to host M-rated content (the Wii, DS, and 3DS) are also the ones with lower average selling points. Another interesting note: M-rated titles grew their percentage of total sales even from 2006 to 2009, when the Wii's E-rated lineup and T-rated rhythm games were supposedly reshaping the industry.

The rise in violent games has also been reflected in the industry's most visible successes. M-rated games actually made up a larger percentage of the industry's offerings in 2005 when the current generation started, but the NPD's top 10 best-selling games chart that year featured no M-rated titles. For the last three years, at least half of the annual top 10 has been rated M.

"M-rated titles grew their percentage of total sales even from 2006 to 2009, when the Wii's E-rated lineup and T-rated rhythm games were supposedly reshaping the industry."

Analysts contacted by GamesIndustry International brushed aside concerns about the game industry becoming more violent.

"I'm certain that the number of violent games isn't materially greater than in the past, but the number of overall games is lower," Wedbush's Michael Pachter said. "Violent games sell better than kids' titles generally, so more E-rated game projects are cancelled, and the same number of M-rated projects are approved when publishers decide to cut back on the number of titles published."

EEDAR's Jesse Divnich agreed, saying, "It does not mean that the quantity of violent games, or the exposure of violent games to our audience is increasing; however, it represents a continued balancing act to match the game content with the preferences of the active audience of a platform. The consumers who made the Wii such a success from 2007 to 2010 haven't disappeared, they've simply migrated their gaming habits to other platforms (mobile, social, Xbox 360 Kinect, etc.), and as such the content shifts with consumer demand."

So the explanation for the traditional PC and console sector's increasing reliance on violent games appears to be, "It's what sells." It's to be expected that publishers would chase that quality so enthusiastically, given how little has qualified for that designation of late. Since the industry's 2008 peak, Nintendo's Blue Ocean turned toxic halfway through the Wii's lifespan. The Guitar Hero phenomenon lived fast, died young, and left a savagely exploited corpse. And dedicated handheld gaming has been a hapless victim in the blast radius of the ongoing smartphone explosion.

In light of these difficulties, publishers have grown more conservative. Instead of boldly reaching out to new customers, they've played to the young male audience they see as their base. They have embraced a more selective philosophy when it comes to releases, trimming their slates to the safest bets, the faithful standbys, the evergreen offerings. On investor conference calls and Powerpoint presentations, the strategy is "fewer, bigger, better." In reality, it's closer to "fewer, bigger, bloodier."

"Gaming has found itself in the same cultural ghetto as comics, and escaping that ghetto increases the potential success for everyone, makers of braindead explosion fests included."

And this is why gaming can't shake its cultural stigma. This is why we still have to deal with mainstream media scare pieces like the one from Katie Couric last week. It doesn't matter how much of the industry is older women playing casual games on Facebook. It doesn't matter how much more effective the ESRB ratings are than ratings in other media. These facts are powerless because the people criticizing games for being too violent are not criticizing Facebook games, and they're not criticizing the ESRB for accurately identifying a depraved gorefest as something parents might not want their kids to see.

These parents and politicians cling to their concerns because the industry as they see it has responded to them by obstinately doubling down on exactly the content they oppose and cutting back production on more edifying fare. And then publishers underscore that fact by blowing untold millions of dollars on marketing each one of these games so that everyone who drives a car, turns on a TV, or walks into a mall can't avoid hearing about all the awesome new ways these games let them virtually kill people.

This is a problem of image. And unlike the problems in AAA games, the industry can't shoot its way out of this one. The only way out is for publishers to take a bolder, more varied, and occasionally conscientious approach to the content they produce.

Yes, games are expensive, and yes, trying something new is risky. But it's ultimately a better investment than churning out yet another annualized sequel to a braindead explosion fest. Because gaming has found itself in the same cultural ghetto as comics, and escaping that ghetto increases the potential success for everyone, makers of braindead explosion fests included. A glance at the Iron Man 3 box office numbers versus the actual comic's sales figures should be evidence enough that there's more upside to a mainstream medium than a marginalized one.

Note: The Entertainment Software Association declined to specify how much of the market was made up of M-rated game sales in 2012, but that data is typically released around the Electronic Entertainment Expo each year in the trade group's Essential Facts booklets. The Entertainment Software Rating Board has said that M ratings held steady at 9 percent of the market.