Sir Ian Livingstone: The first Knight of the nerds

"I am never going to retire, I don't see the point"

It's remarkable to think that not a single UK games industry person has ever received a knighthood or damehood before.

This is the country responsible for Grand Theft Auto, Tomb Raider, Lemmings, Total War, Donkey Kong Country, Forza Horizon, Wipeout, Worms and many of the biggest video games in the world. Yet, even though numerous people from the worlds of movies, music and sport are awarded such honours every time they are announced, the video games industry ends up empty handed.

Until now.

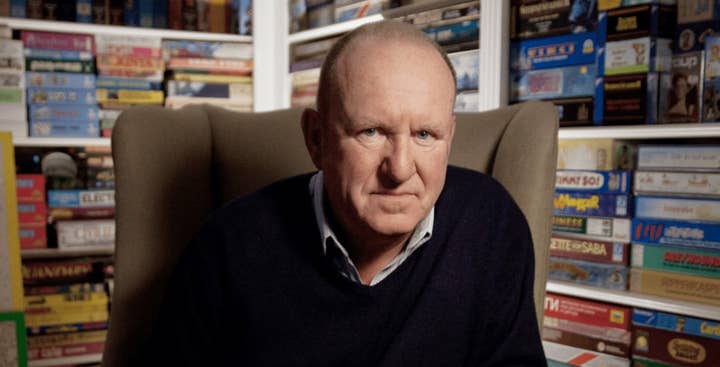

"It's really unbelievable, I'm still adjusting to it," Sir Ian Livingstone tells GamesIndustry.biz. "I got a letter yesterday to Sir Ian Livingstone and I said that can't be for me, that's far too grand."

Livingstone said he hadn't seen it coming, but that's not the case for the rest of the games business, who have been calling him 'Sir' for many years. Now it's official, and Livingstone believes it's another moment where the games industry is starting to get the sort of recognition that its sister industries have enjoyed for decades.

"I guess you could say it was love at first sight when they opened the door and there was Lara Croft on the screen"

"I've always believed that the games industry has been underrepresented with regards to awards and somebody had to be given a knighthood or a damehood at some point soon," he tells us. "Compared to the other creative industries it didn't seem very equitable considering how well the UK punches above it's weight in terms of content creation. Clearly I'm delighted it's me, but it does, at long last, recognise this incredible UK video games industry."

He continues: "The trouble with the games industry is it does not have celebrity. TV, film, music, advertising, all have known celebrities, and they appear in the newspapers and on television. Beyond the games industry, nobody knows who the people are who make the games. People don't even think about where they are made but those who do, they think it's in the United States, or Japan, or perhaps China, but they never think of the UK as being at the forefront of creation. And that's a shame, but hopefully that will change.

"We've seen how successful the industry has been through the pandemic. Not many companies have had to furlough anybody, the consumption of games is digital, the creation of games is digital, developers have been able to transition to working from home using cloud-based systems. And games are just kind of future proof because it ticks all the right boxes for the post-COVID economy. It's creative, knowledge-based, high skills, high salaries, digital export focused, it's direct to consumer, global in scale, regional, not dependent on being in London... And the number of companies who have become incredibly valuable in very short order is phenomenal and that should really be reported a lot more."

Livingstone's career in video games has included transforming digital education, investing in and supporting studios of all sizes, and launching the iconic Tomb Raider series. But his career in games overall stretches further back.

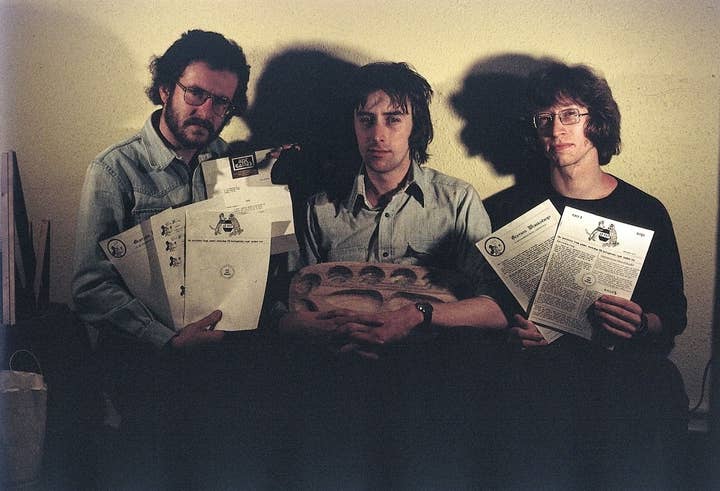

The story begins with the Owl and Weasel fanzine. The newsletter, edited by Livingstone and Steve Jackson, was dedicated to board games, and a copy ended up in the hands of a certain Gary Gygax, who sent the duo a copy of his new game: Dungeons & Dragons.

"It was in a plain box," Livingstone remembers. "But when we opened the box, it opened up our imagination like no game had done before. And I don't think any game ever will. It was the first roleplaying game where you assumed the roles of heroes and wizards and clerics and thieves, and going on these fantastic journeys of the mind, this theatre on the fly, exploring a dungeon that someone else has created, killing monsters and finding treasure. That was a milestone in gaming history."

Livingstone and Jackson ordered six copies of the game, which was all the money they had, and this was enough for them to secure a three-year exclusive distribution agreement for D&D for the whole of Europe.

"It was one of the advantages of a fledgling games industry is that you could get these preposterous deals, because nobody was doing it."

Livingstone and Jackson had a mail order business, but it was tough. They both continued their day jobs because it wasn't growing, and when they finally decided to get a bank loan to try and fund the business properly, they didn't get it.

"We had gone to the States in 1976 to meet Gygax and sign up all the fledgling games companies, ordered a load of stock that we didn't have the money to pay for, and asked them to send it to my girlfriend's flat, because we had given up our own flat," Livingston says. "We came back to the UK with nowhere to live. We found a really small office in the back of an estate agent... we used to call it the bread bin because it was so small. If anybody came in, one of us had to leave [laughs]. Steve Jackson had a van, which we slept in, and we parked outside the office. We joined a local squash club so we could have a shower and shave in the morning.

"So it was mail orders from 9am till 1am, into the stinky van, and then to the squash club at 7 or 8 in the morning. We had this small triangle of life in Shepherds Bush."

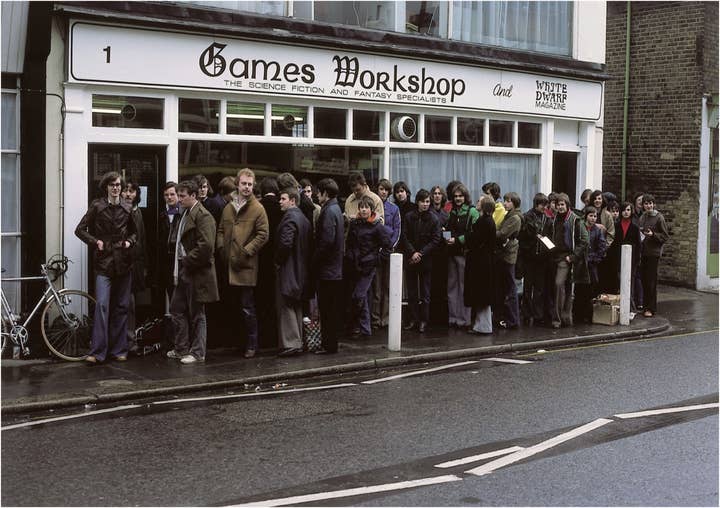

But slowly they built up the business that became Games Workshop. The first shop opened in 1978, and Livingstone and Jackson eventually sold up in 1991. The business continues to operate today, now dedicated to the Warhammer franchise.

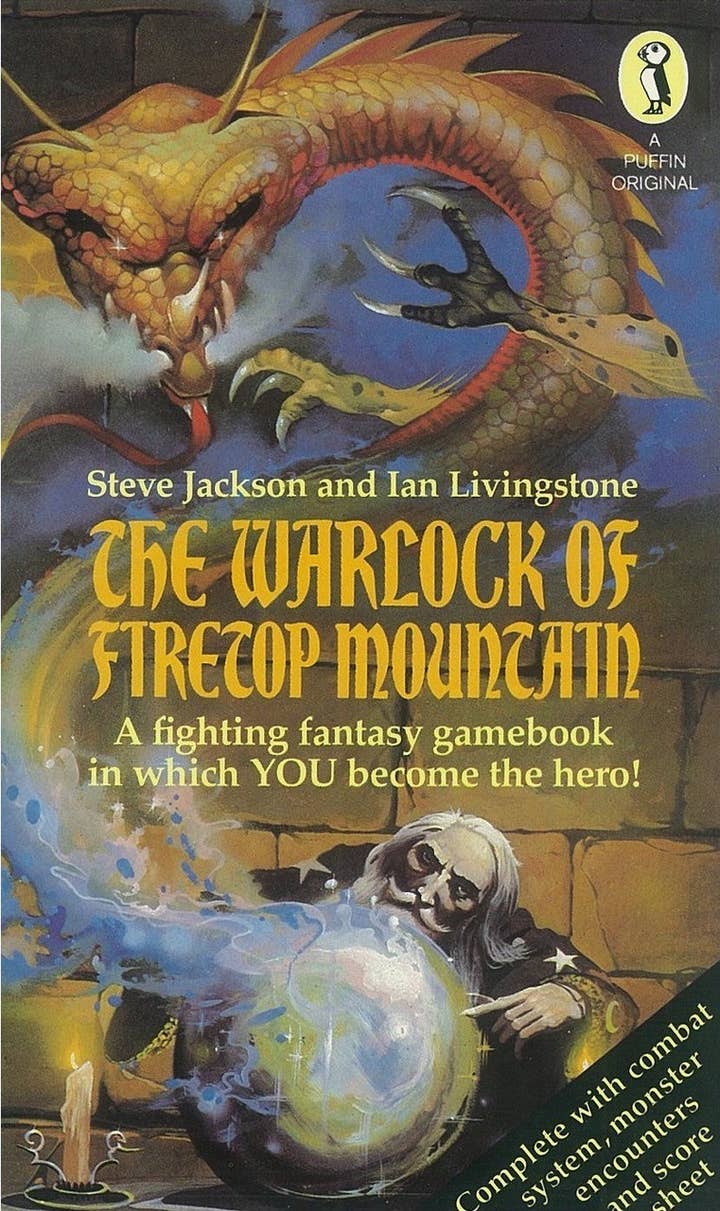

If the 1970s marked the birth of Games Workshop, 1980s was about the creation of Fighting Fantasy. Beginning with The Warlock of Firetop Mountain in 1982, these gamebooks -- written by Livingstone and Jackson -- asked readers to choose what the character did, while also rolling dice to fight monsters and overcome challenges.

"That was a very big proud moment when we saw those copies in WH Smith and we had no idea of how successful it was going to be, neither did Puffin Books the publisher," Livingstone remembers. "I mean they reprinted the first book, I think it was 11 times in the first few months before they realised they got a hit on their hands."

The books were quite radical in how they engaged an audience of children who were previously not interested in books, and they went on to sell 20 million copies.

"The criticism around games at that point really confused me because you had this whole kind of generation of children reading," Livingstone says. "It was empowering making these decisions at the end of the paragraph, whether to turn left or right or fight the monster or not, and working through these books was effectively critical thinking... it encouraged creative writing, it increased literacy apparently by 17 percent. I think another reason why the games industry has had a bit of a bad rap is that people just don't understand the educational value that games do provide."

Fighting Fantasy's initial run ended in 1995, before being resurrected today, with Livingstone contributing new stories to the series, including one for this year's 40th anniversary.

One of the more successful Fighting Fantasy books was 1984's Deathtrap Dungeon, which went on to sell 400,000 copies. This caught the attention of Dominic Wheatley and Mark Strachan, who had set up a new games publishing company called Domark. The two visited Games Workshop and asked Livingstone to design their first game: Eureka.

The game was programmed in Hungary, and developed in secret, as there was a £25,000 prize for the first person to complete it. Livingstone even presented the cheque to the winner.

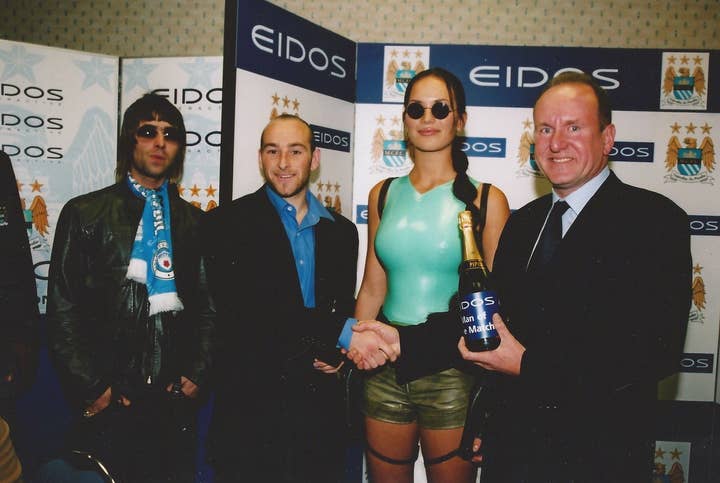

Instead of taking any royalties, Livingstone took equity in Domark, and after the sale of Games Workshop, he invested even more into the publisher. Livingstone joined the board as vice president, but it was a tough time, even with the success of games like Championship Manager. Eventually, Domark merged with a group of companies and Eidos Interactive was born, which floated on the stock exchange in 1995.

Livingstone was now executive chairman and in charge of product, and the big moment arrived when an opportunity came to acquire CentreGold, which owned several businesses, including the game developers Silicon Dreams and Core Design.

"I was tasked with doing all the due diligence on the content and studios," Livingstone begins. "I remember it to this day. It was a snowy early March day and I went to Silicon Dreams near Oxford. And it was okay, they were doing some nice football games. I didn't really fancy driving over the Pennines because it was snowing but I was coerced in to it [laughs] and we drove over to Derby to Core Design and met Jeremy Heath-Smith.

"Jeremy, fantastic personality, showed me around the studio and all the games in development and in the last room... I guess you could say it was love at first sight when they opened the door and there was Lara Croft on the screen.

"And so I met the very small team, Toby [Gard] and Paul [Douglas] and the rest, and was just kind of mesmerised by what I was seeing. Games at that time were all 2D side scrolling, and here was one of the very first games to be developed with a 3D character going in to a 3D world. It had these incredible graphics and the fact that you could not just move in to the environment but you could move the camera and could look up and down... it was phenomenal. There was puzzle solving and adventuring and the combat and, last but not least, it was a female character. Well... to say I was enthusiastic was a bit of an understatement, although I tried to hide it."

With the help of Lara Croft, Eidos became a billion-dollar valued company by the end of the 1990s. The firm would face challenges in the early 2000s, but ultimately found a home at Square Enix, and Livingstone remained part of the company -- and working on Tomb Raider -- right until he left in 2013.

Just before Livingstone's time with Eidos/Square Enix came to an end, the games veteran made another significant contribution to the games industry by co-authoring the Next-Gen Skills Review.

"I'd whinged to Ed Vaizey, who was the culture minister at the time, about the fact that there was not enough software engineers of the quality to be in the games industry, let alone in all the other creative industries," Livingstone says. "And so he threw it back at me and said 'Well, why don't you write a review?' He got the funding, got Nesta on board -- who did all the heavy lifting in the research -- and we wrote the Next-Gen Skills Review."

The review was transformative, and resulted in significant changes to how students were taught computer science.

"We were frustrated that children were being taught how to use other people's software, and given no insight in to how to create their own technology. That was like teaching children how to read, not how to write, that they could play a game, they couldn't make a game, they could use a website, not build a website. So we wanted to move them form the passenger seat in digital, in to the driver's seat, so they would be able to determine their future."

Post-Eidos/Square Enix, Livingstone initially became an angel investor and worked with some successful studios, including Golf Clash creators Playdemic and Fall Guys developer Mediatonic. And he has a portfolio of investments still today.

In 2015, he became the chairman of Sumo, one of the UK's biggest games studios. The company, which has developed games such as Crackdown 3, Sackboy and Team Sonic Racing, floated in 2017, and is currently going through the process of being bought by Tencent for £1.3 billion.

His current 'day job', as he calls it, is as co-founding partner of Hiro Capital, and investment group that has raised $135 million to invest in games studios, technology, esports and 'digital sports.'

"It's been interesting to me going from a content creator to a content backer," Livingstone says. "But we don't just offer companies money. We offer them our expertise."

On top of all that, and following the Next-Gen Skills Review, Livingstone has also just opened his own Academy. Livingstone continues to be vocal about education, and how the system could benefit from a bit of game-like thinking.

"This deflation of people's aspirations early on through examinations is wrong"

"When you think cognitively about what you're happening when you're playing games... you cannot get through a game without problem solving. You learn intuitively. You can fail in a safe environment. You're not punished for making a mistake. If you can't get through a game, you're encouraged to get through it and over time everyone becomes better. Whereas in an examination, you have this one moment in time where you have standardised questions, where if you get it right you're judged a success, if you get it wrong, you're judged a failure. This deflation of people's aspirations early on through examinations is wrong."

He continues: "Someone said to us: 'If you're so passionate about this, you need a flagship school'. And I was like 'yes we do', so we set off. But I quickly realise that I had no ability to run a school, so eventually teamed-up with Aspirational Academies Trust. I am delighted to say the Livingstone Academy opened last year. It is from reception to sixth form. It will have 1,500 children over time, but of course you can open to one cohort per annum. We had 150 places available for Year 7, but we had 450 people apply. That was fantastic in that it seemed to resonate with parents, but disappointing that we had to turn away quite a few children.

"It's a £30 million project. It's not a private school, it's a state school. The only difference is in the way you are taught."

Livingstone's journey from someone who couldn't get a bank loan for what was almost certain to be a successful mail order business, to someone investing millions in studios, and turning them into billion-dollar acquisition targets, has been an incredible story. But even with his knighthood, there's no plans to stop.

He is still investing and working with studios, but ultimately he's most comfortable in the creative space. He likes making things. And that includes a new Fighting Fantasy and the upcoming Dice Man book, which tells the story of the first ten years of Games Workshop. He's even designing some new board games that can sit alongside the 1,000-plus he owns.

"The one reason I've never wanted to retire having been in this industry for 47 years is it's not just the medium of games, it's the people in the industry," he says.

"Because of that lack of celebrity, the people tend to be very humble, and collaborative, and cooperative, and there's a real feeling of comradery in the industry.

"[Laughs] You could call me the Knight of the Nerds. But that's with pride, not in any way trying to apologies or think that people who enjoy games are odd. Games are perfectly natural, it's the people who don't play games who might be the strange ones.

"I'm never going to retire, I don't see the point. There's an awful lot still to do. Life is a game for me. And games are my life."