Rebellion: "Nobody here ever bothers with Metacritic"

CEO Jason Kingsley on how the rise of Twitch and YouTube has allowed Sniper Elite to thrive in the face of mixed reviews

In the weeks before AOL closed the site for good, Joystiq took a bold step against convention and on behalf of its readership: It ditched scored reviews. Last week, our sister site Eurogamer did the same, and it seems increasingly likely that other sites will soon follow.

For anyone earning a living from reviewing games these will seem like radical times, but the undeniable fact is that the press could no longer ignore the larger forces at work in the industry. As 2014 drew to a close, a string of messy, broken and simply unfinished products cast an unflattering light on the compromises professional critics have to make to get their opinions out into the world on the day of release. The public was angry, and rightfully so.

"Getting a bad product out on time can, and will, damage your reputation as severely as getting a good product out very late"

For Jason Kingsley, the owner of Rebellion and one of the most prominent figures in the British industry - he is, after all, an OBE - that run of deficient AAA releases was a concern, if not exactly a surprise. As the CEO of an independent studio, one that has retained that status through profound change and upheaval, he understands the pressure involved with making and releasing big games. Add to that the grand scale of blockbuster development in 2015, the whims of external shareholders, and the volatility of the online infrastructure, and a flashpoint like this was bound to happen eventually.

"There's a pressure to get the product out there," he says. "But the problem is that getting a bad product out on time can, and will, damage your reputation as severely as getting a good product out very late. It's the devil and the deep blue sea.

"It will have a short-term effect. I don't think it'll take very long for people to think, 'Company X released a faulty product and screwed us over.' I'm not talking 'faulty' as in a few bugs and idiosyncrasies, but something that, on the face of it, is horribly broken. I think we can see it when something really shouldn't have been released. It will have a short-term effect, and I think we'll see changes in the way games have to be made as a result.

"It also damages games in general, because it convinces people that they're all buggy and broken, and they paint every game with the same brush. You can lose your consumer that way."

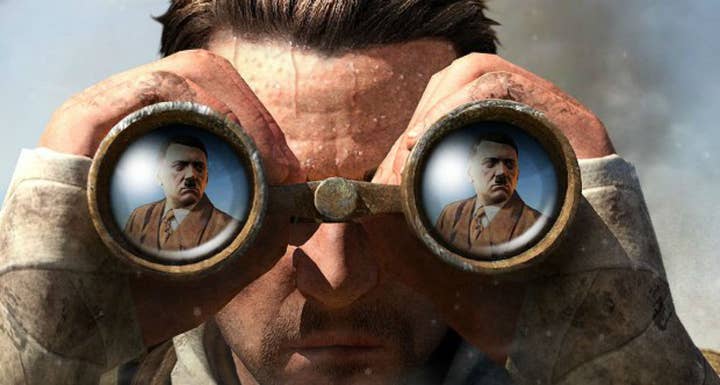

From that perspective, this point of crisis represents a challenge for Rebellion. Sniper Elite, without question Rebellion's most important IP, is aimed at a similar audience to the unfinished games that caused such consternation at the end of last year. If Kingsley fears that consumers may develop negative assumptions about games as a whole, that could easily apply to its tentpole franchise. If there's any seed of doubt, Kingsley doesn't let it show. The over-reaching ambition of the major publishers, he argues, actually leaves the door open for Sniper Elite to expand its audience.

"From a business perspective, Sniper Elite is a slam-dunk certainty. And that's interesting"

"Every Sniper Elite game we've released has debuted at number one, and everybody says, 'God, that's unexpected. It's a sleeper hit. But it's not really a 'sleeper hit' because it sold as well as projects that cost ten times the amount to develop and probably had 20 times the marketing budget. From a business perspective, it's a slam-dunk certainty. And that's interesting."

And it's interesting for two reasons, in particular, the most obvious of which is the glaring disparity in resources behind Sniper Elite relative to its blockbuster competitors. Rebellion has somewhere in the region of 200 employees, but the size of the development team on Sniper Elite v2 - or the size of its marketing spend, for that matter - was of an entirely different order to the typical console retail game expected to be a bestseller. And yet when Sniper Elite 3 got comfortable at the summit of the UK charts in 2014, it held the likes of Watch Dogs and FIFA 15 at bay.

This is clearly a point of some pride for Kingsley, and understandably so. Speaking to Eurogamer in the summer of last year, Kingsley confirmed that Sniper Elite v2 had sold 500,000 units on Steam alone. Add that to console then stand it next to the production budget and it becomes piercingly clear just how influential the franchise could be in terms of the studio's future. Rebellion's long-term goal, Kingsley says, is to be as self-sufficient as possible, creating its own IP and publishing its own games for its own customer base. That future must necessarily be built on success, and Sniper Elite, though still co-published by 505 Games, is laying the bedrock.

The second interesting aspect is highlighted by Kingsley, circling back on the subject of the changing role and shifting responsibilities of professional reviewers. Sniper Elite, you see, has never been the subject of fawning praise from the critics, with Metacritic averages for Sniper Elite v2 and its sequel falling around the mid-60s. There was a time, not too long ago, when that kind of score was enough to scupper a job opportunity or even a bonus, in the belief that big scores are a fundamental aspect of strong sales.

Sniper Elite disproves that notion, its "solid, but a bit disappointing" scores doing nothing to harm its fortunes in the marketplace. Gamers, meanwhile, were almost universally more positive.

"Nobody here ever bothers about Metacritic," Kingsley says. "We think of it as irrelevant, quite frankly. We only concentrate on what the users think, and every aggregate user score has been significantly higher than the aggregate professional score. We care about the people who are spending their money, and whether we're happy that we've made a good game. The acid test isn't somebody's abstracted number.

"Every aggregate user score has been significantly higher than the aggregate professional score"

"Professional reviewers have a very difficult job, because they cannot see a game from the perspective of somebody who's paid money for it. Because that's their job. Your average player who buys the game is almost obligated to try and enjoy it. They're hoping this thing they've paid for is good, and if it's crap they're very, very disappointed indeed and they probably won't buy another game from you. I'm not saying professional reviewers try not to enjoy games, but that's what they do during the week as a profession, with all the pressures and deadlines that come with it."

With all of this in mind, the apparent bravery of the press in discarding review scores takes on a different complexion. The time when that practice adequately served either the product or the audience has long since passed, and it shouldn't have required such a dismal period of broken releases to finally tip the balance. Indeed, that insistence on abstract scoring systems has anchored the way the press examines and evaluates games firmly in the past, even as the internet demonstrated, time and again, just how much more creative, detailed and, crucially, useful the form could be.

On a personal level, I purchased Far Cry 2 not because of its review scores or even brand recognition, but because of the blogger Ben Abraham's accounts of playing the game while deliberately enforcing permanent death. The same is true of The Sims 3, and Robin Burkinshaw's wonderful role-playing experiment Alice & Kev. That was 2009, and there was nothing even remotely similar to that being generated by the press. Despite the new freedoms afforded by the fluidity and immediacy of the internet, commercial games coverage has remained grounded in a carousel of previews and reviews - a structure created to serve magazines.

"Professional reviewers have a difficult job, because they can't see a game from the perspective of somebody who's paid money for it"

As someone who rode that same carousel for five years, I can say with confidence that the indolence shown by the press in this area is only partly due to the sluggish nature of large organisations. The simple fact is that reviews - in their classic form - are the low-hanging fruit of games coverage; a rigid, undemanding format enlivened by the addictive tang of emphatically stated authority. The alternatives, though well within reach, were simply more difficult to contemplate and execute. That's how self-starting individuals like PewDiePie and TotalBiscuit managed to steal a march on those with the equipment, resources and reach to get there first. Commercial games coverage will change irrevocably over the coming years, and that will be down to YouTubers, Twitch and the long overdue recognition that review scores are little more than dead weight.

For Kingsley, this is the landscape in which companies like Rebellion have always wanted to operate. One where the lines of communication aren't mediated by a handful of paid professionals, the common view of any given game orchestrated by their personal tastes, unencumbered by the need to actually pay for the product. For Sniper Elite, with its laser focus on polishing a handful of specific, sticky and shareable game mechanics, that made all the difference.

"The greatest value for us as digital publishers, if you like, is in embracing YouTube and Twitch and the normal people being seen playing our games," Kingsley says. "It lets you see what the gameplay is like, and make a decision on whether you like that and want to play it. You might not actually care whether it didn't seem totally original to one person, or that the story was a bit crap.

"That new approach has taken over."