Why the European Court of Justice's decision on cheats is not a milestone | Opinion

ADVANT Beiten's Dr Andreas Lober analyzes the impact of the Sony vs Datel case – and shows that operators of online games still have plenty of options to take action

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) is the highest court in the European Union. Decisions regarding video games are few and far between. So when it rules, we expect the decision to be a game changer.

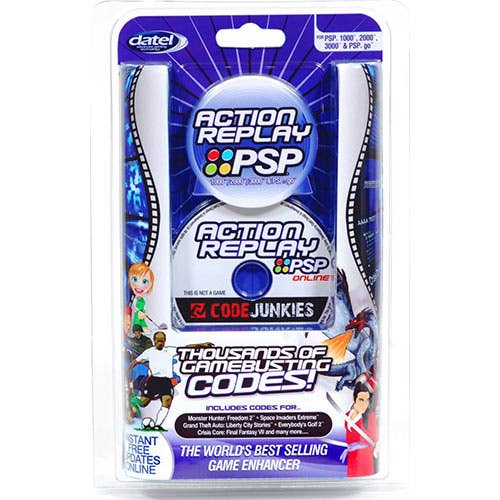

The judgement it delivered on 17 October 2024 – ruling against Sony in a dispute over cheats provided through Datel's Action Replay for PSP – looks like one at first sight. A second look shows that for most cases it will not change anything. The reason for this is that lawsuits against cheat software developers, especially in multiplayer online games, are now based on violations of the game developers EULAs and competition law.

The ECJ case, however, is different. It is about the software Action Replay PSP and Tilt FX PSP, which gave super powers for various games on Sony's today nearly forgotten Playstation Portable. Sony originally won an interim injunction back in 2010 at the Regional Court in Hamburg, as well as two years later the case on the merits. The cheat producer went into appeal, and the decision was reversed nine years later in 2021.

The German Federal Court of Justice then sent the case to the ECJ. National courts can do that if they have doubts about the interpretation of EU law. As a reminder: the German Federal Supreme Court (Bundesgerichtshof) had already rendered two decisions regarding cheats for World of Warcraft (as of 6 October 2016 – case I ZR 25/15, and as of 12 January 2017 – case I ZR 253/14).

When the German Federal Supreme Court now submitted the case to the ECJ, it is not because the judges have changed their mind and became cheater friendly in the meantime. It was because the relevant question of law was another one. The question was whether Action Replay PSP and Tilt FX PSP infringe copyright even though they did not interfere with the source code and the software itself, but just modified variables in the computer's RAM. The ECJ held that this is not sufficient to assume a copyright infringement.

The questions which were relevant in the World of Warcraft cases just were not on the table here (this might have something to do with the fact that Action Replay has been brought to court nearly 15 years ago, when it might not have been as clear what instruments publishers have against cheat bots, and also with the fact that it is not about cheating in a multiplayer game).

For publishers of single-player games wanting to act against cheat software, the ECJ Action Replay decision is not good news. According to the ECJ, messing around with games is not necessarily a copyright infringement if the game software is not touched.

For publishers of single-player games wanting to act against cheat software, the ECJ Action Replay decision is not good news

There are still some instruments remaining, though: For example, offering such cheats might still be an act of unfair competition. This aspect was only briefly discussed in the German Action Replay decisions, and not at all by the ECJ. This aspect is especially relevant for games monetized through microtransactions.

It might also be possible to validly agree in the EULAs that the game must not be used with cheat software. This aspect was only mentioned in a sidenote by the advocate general in the Action Replay decision, and – for procedural reasons – did not feature in the German decision, nor in the ECJ decision. Finally, depending on the name of the cheat software, it may infringe trademarks or title rights.

Publishers of multiplayer games will have less to worry about. Numerous courts have found cheats for multiplayer online games to be illegal. One of the more famous cases is Bungie vs. AimJunkies. While this has been decided in the US, there is no reason to assume that the outcome would have been different in the EU – neither before, nor after Action Replay.

The German Federal Supreme Court has confirmed this with its two decisions in the past regarding World of Warcraft, as have other courts. These two decisions are not put in question by the new ECJ decision, as the subject matter is different. From the perspective of most players because the World of Warcraft decisions are specifically for multiplayer online games.

One of the World of Warcraft decisions dealt with the question of whether the manufacturers who had developed the cheat software had the right to use World of Warcraft for commercial purposes, i.e. the development of the cheat software (which is a discussion based on copyright law). The other decision was around the question of whether the respective cheat's impact on the game was an unfair interference and hindered Blizzard to present its game on the market in its originally intended way (this is an argument based on unfair competition law).

The first of these questions was not discussed in the Action Replay cases, and for the second one, Sony did not present enough evidence. Thus, publishers of multiplayer online games can still rely on established case law when acting against cheat software.

In addition, there are numerous other aspects that can be relevant, depending on the details of the case at hand (such aiding and abetting to copyright infringement of the users playing the game in violation of the EULAs when using cheat software, the circumvention of technological protection measures or modification of the game's look and feel).

Publishers of multiplayer online games can still rely on established case law when acting against cheat software

Now, finally – did it matter that Action Replay was litigated in Europe and Bungie vs. AimJunkies in the US? Presumably not that much. The relevant aspects for litigating against cheat bots for multiplayer games are essentially similar, even though the legal traditions and the procedure are different.

Publishers have a wide choice where they bring such matters to court. Suing the infringers where they are based can be a logical choice. It facilitates the enforcement of court decisions against the infringer. The geographical scope of the decisions of the court where the infringer is based is also potentially wider.

However, there might be other aspects to consider, e.g. how robust and fast the legal system is, or the respective costs. Germany, for example, has plenty of case law and the courts often render interim injunctions quickly. In the US, however, the procedures might be more expensive, but it can be easier to get that missing piece of information through discovery. Thus, there are many aspects to be considered.

Dr. Andreas Lober is a partner at the law firm ADVANT Beiten. He has been advising video game companies for many years, and has been involved in a variety of legal proceedings against publishers of cheat software. The views expressed in this article are his personal opinions and conclusions.