Why aren't more Japanese developers crowdfunding?

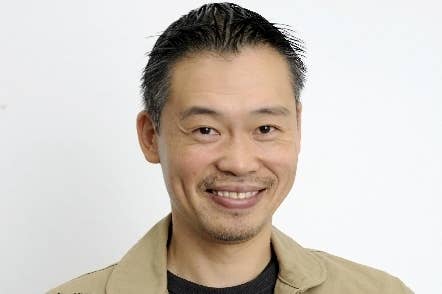

Keiji Inafune talks about Mighty No. 9 and why the Kickstarter challenge for Japanese creators goes beyond simple logistics

In recent years, crowdfunding has enabled a long list of veteran developers to revisit their roots with the type of games that made them famous, whether or not those projects would find interest from publishers. One thing they almost all have in common is that they're Western developers. For all the good will and devoted fans that Japanese developers have, very few of them have made a splash on Kickstarter.

One exception to this is Comcept founder Keiji Inafune, who last year raised more than $4 million to create Mighty No. 9. The game is intended to be a spiritual successor to Mega Man, a franchise on which Inafune played a key role during his time at Capcom. Speaking with GamesIndustry International earlier this month, Inafune said there are high hurdles for Japanese developers to clear in order to start crowdfunding, and they go beyond the logistics of language and platform limitations on where projects are based.

"Currently a lot of Japanese developers can't actually tell what the North American audience wants."

"Of course there are the language barriers, but it's not just that," Inafune said. "Looking at the data for the backers of Mighty No. 9, approximately 60 percent of those people were from North America. So of course, the Japanese developers would have to make something that appeals to the North American audience, and currently a lot of Japanese developers can't actually tell what the North American audience wants. And until they learn how to be able to do that, that's one of the biggest hurdles."

As for how they can do that, Inafune said it could be as simple as understanding which Japanese games are popular in North America, what sells well and has sold well in the past.

"For example, with Capcom and Bionic Commando, that game wasn't really a big hit in Japan but it sold quite well in North America," Inafune said. "The people in the company didn't fully understand this, so it was hard to get them to understand there's still a possibility for profit here, still a possibility to make a good game from something like this. Until we can understand the American market in that sense as well, it's going to be hard for other private [Japanese] companies to get into Kickstarter."

Mighty No. 9's successful funding (it originally targeted a $900,000 funding goal) suggests a new old school-style Mega Man game is something the North American market would be very interested in. But it wasn't too long ago that Capcom offered exactly that with Mega Man 9 and Mega Man 10. When asked if the reaction to Mighty No. 9 seemed more enthusiastic than the latest actual Mega Man sequels received, Inafune chalked it up to perceptive fans.

"On the surface, a Mega Man game would be more what people might want," Inafune said. "But when it comes down to it, it's more about the soul, the actual inside of what the game is and what it's about, rather than whether the actual robot is blue or not. And I believe the fans are definitely looking at the soul of the game itself, rather than just the surface."

That enthusiasm from the fans is not entirely without drawbacks. In December, Comcept announced the hiring of Dina Abou Karam as its community manager on its Kickstarter page. The post featured a piece of fanart she drew depicting a female version of the game's main character, and a portion of the audience angrily took to the comments, expressing concerns that Karam would push a feminist agenda into the game.

"We don't want to rely entirely on crowdfunding, but it is very important to us that we can make something we want and the fans want."

"There's probably no perfect community manager," Inafune said of the flap. "It doesn't matter who would be hired to do the job; nobody's perfect. But I trust that Dina will be able to do her job, and I trust her from here on out to hold up and help the community."

Despite the headaches that could be caused by going against his own community, Inafune is unconcerned that such controversies could recur whenever his creative choices on the game are questioned by the passionate people who funded the endeavor in the first place.

"I'm not worried at all," Inafune said. "We have been getting the money from the fans who want this game made, but one of the big differences is there's not the bureaucracy of publishers telling you what you have to do and what you can't do. Of course, in the community, everyone wants something else, so we'll look at those things individually and go from there."

Even with the occasional fan friction, Inafune said the crowdfunded development process has felt entirely new and different in a good way. But unlike some of his fellow crowdfunded developers, Inafune has no aspirations to completely move away from more traditional development models.

"We don't want to rely entirely on crowdfunding, but it is very important to us that we can make something we want and the fans want," Inafune said. "So if there is another situation where it's something that fans want to be directly involved in, there is the possibility of another crowdfunded game. But that's not the only option and we're thinking of many other ways as well."