The violent game debate is over

A year after Newtown, the industry is getting all the defense it needs from games it never wanted to make in the first place

The great American debate over violent video games is over. Like cigarettes being good for you, pro wrestling being real, or 9/11 being an inside job, the idea that a few hours of Grand Theft Auto can turn well-adjusted kids into middle school Manchurian Candidate killers is being clung to by a vanishingly small portion of the population.

I bring this up because this week marks the anniversary of game industry figureheads meeting with Vice President Joe Biden to discuss what can be done to prevent mass shootings like the one that took place in Newtown, CT, the previous month. As with any unspeakable tragedy, there was tremendous pressure put on politicians to make sense of something senseless, to assign blame and pass laws to ensure such horrors could never happen again. In the wake of Newtown, the spotlight shone on three potential culprits: guns, the mental health system, and violent video games.

"The debate has been won on the legislative front. It exists now only in the cultural arena, and even there only for a small window longer."

While I didn't expect Obama and Biden to believe games were anywhere close to the root of the problem that the other two subjects represent, they did seem like the easiest scapegoat. After all, opponents of gun control in the US wield an incredible amount of political influence (more states responded to Newtown by loosening firearm restrictions than tightening them) and reforming mental health care in the US carries all the logistical headaches of reforming general health care (see the agony surrounding Obamacare), and combines it with the challenge of eradicating profoundly entrenched cultural stigmas. Given that, I was legitimately concerned that throwing games under the bus would be the most politically expedient course of action for the administration.

I can't say how seriously Biden and President Obama were considering pushing for laws regulating violent games, and how much their calling of game execs to the principal's office was just to appear open to options beyond gun control. But I hope I am accurate in saying that was the last moment in my life I would ever feel legitimate concern that wrong-headed legislators would constitutionally quarantine games from the rest of the creative arts.

It was a brief moment of panic, a fleeting worry that a groundswell of public support would overrule the 2011 US Supreme Court verdict ensuring games would have the same constitutional free speech protections as any other creative art form. But that moment has passed. President Obama instead called for more research into the effects of game violence on kids, the findings of which would have almost no chance of spurring legislation, barring some sort of smoking gun. (Then again, the NRA has shown that even with a literal smoking gun, these sorts of laws are not always easy to pass.)

So the debate has been won on the legislative front. It exists now only in the cultural arena, and even there only for a small window longer. What remains now is the final push to take the impact of violent games on mass shootings from "different angle on a tragedy that may help fill time on a 24-7 cable news network" to "even Fox News wouldn't suggest this with a straight face." I believe we've actually crossed that threshold now, and can only hope I never have an opportunity to be proven right. And as much as I might congratulate the Entertainment Software Association on this development, it would be for good fortune as much as good planning.

"What will finally inoculate the major players the industry from this sweeping criticism is the rise of games they would never have published..."

After decades of dealing with this issue, the tipping point was not a refinement of the ESRB rating system, a PSA campaign with cherished professional athletes, or a fundraiser to support the creation of educational games. Those are all fine and good, but they've been done plenty of times, and they haven't clinched the debate. What will finally inoculate the major players the industry from this sweeping criticism is the rise of games they would never have published, games with introspective stories about straining family ties, exploring the difficulty of maintaining a healthy work-life balance, or coping with a child's terminal cancer.

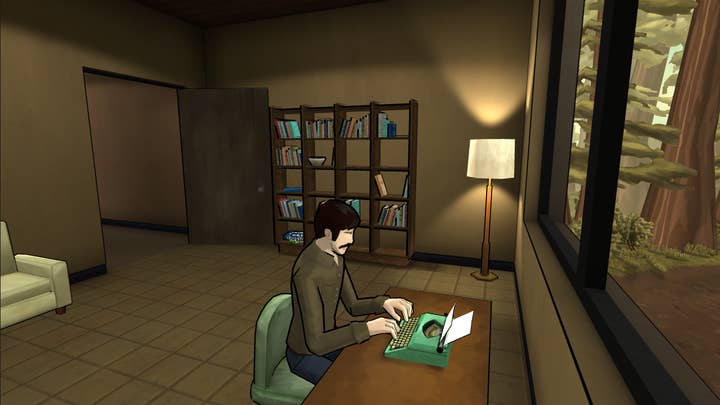

It's no coincidence that games like Gone Home, The Novelist, and That Dragon, Cancer are emerging from outside the framework of the traditional gaming industry. From the way they're made to the way they're marketed, these games run counter to everything mainstream gaming has been doing for decades. They are the products of extremely small teams, with similarly tiny budgets. They are digitally distributed, avoiding all the expenses related to getting a game in a box on Walmart's shelves. They aren't planned for traditional consoles (at least not yet), where games must pay to go through the ratings process. In the case of Gone Home and The Novelist, the creators are selling their games directly to consumers (although those who prefer can grab them off Steam).

Despite their outsider status, these games represent the industry's best chance of making the mainstream reassess what games are and the respect they should be afforded. Until now, the non-gaming masses have split games into two general categories: colorful toys for children and ultraviolent toys for manchildren.

Did that last statement make you pause? Are you thinking of counter arguments, games that don't fit into either category in any way? If so, it's probably because you understand the industry well enough to see the nuance, to spot that oversimplification. Lots of non-gamers don't. So when they hear the game industry described as "a callous, corrupt, and corrupting shadow industry that sells and sows violence against own people," they compare it to what little they know of the industry. And every holiday season, the industry spends a whole lot of money to make people think it exists solely of Battlefield, Assassin's Creed, Grand Theft Auto, and other nasty-sounding titles.

Fortunately, this new breed of higher profile narrative-driven games, commercially viable titles that would rather explore a collapsing relationship instead of collapsing skyscrapers, give the industry clear counterpoints to its critics. And once people accept that the medium is not a monolithic entity, that just as with film and books and music, the best-sellers don't come close to encompassing all that is possible with the art form, then the argument shifts. At that point, the object of the outcry transitions from the medium to specific entries therein. There will always be button-pushers, headline-grabbers, experimental works that attempt to shock the conscience. But winning this debate means that from this point forward, the onus of answering for these potentially offensive works will fall more squarely where it belongs, on the people who create them instead of the medium as a whole.