The right way to monetize kids?

Nerd Corps president Ken Faier explains how to make a transmedia hit without cutting ethical corners

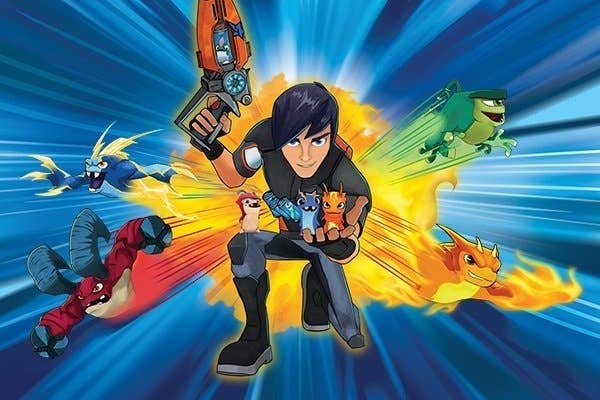

2014 was a big year for Nerd Corps Entertainment. After eying an expansion into interactive entertainment since the days of the DS, the animation studio had its first significant video game success with Slug It Out, based on its own Slugterra cartoon. And after a dozen years forging its own path, the studio behind properties like Kate & Mim-Mim, League of Super Evil, and Storm Hawks was acquired by Canadian family entertainment firm DHX Media in a deal worth up to $57 million.

Speaking with GamesIndustry.biz, Nerd Corps president (and now DHX senior VP of content and GM of kids & family) Ken Faier said his studio was an attractive pick-up for DHX because of its track record creating brands that could become hits in an increasingly competitive market.

"Right now the quality level of kids entertainment has gone up tremendously because it's just so much more difficult than it used to be," Faier said. "There used to be lots of shows that would hit Saturday morning that were paid for by toy companies with bad writing, bad animation... They tried to cheap out on that because it was really just a marketing expense. They wanted to create a quick fantasy to sell the kids more plastic."

"Right now the quality level of kids entertainment has gone up tremendously because it's just so much more difficult than it used to be."

In the '80s and '90s, that strategy could work just fine, Faier said. There were only a handful of networks, and companies able to wrangle their way into a time slot could be assured a reasonable return on their investment. But now with the market more fragmented, with more channels than ever, each of them offering a smaller portion of the audience, the strategies have changed. For Nerd Corps, that means transmedia plays like Slugterra, a cartoon with multiple toy lines (plush dolls, action figures, NERF-like guns) that contain codes to unlock content on an official website and in its mobile game.

"It's harder to build brand, so you need it to be good," Faier said. "It's got to be one where kids will want to play the game, the online game, where they'll want everything that's there and it's all a pretty good experience. You put a bad one out and you start to lose them. They'll go to the next one that's pretty good."

For Slugterra, the formula appears to be working. The mobile game has seen nearly 2 million downloads on iOS and Android, the website has 350,000 registered users, and Nerd Corps has seen a 13 percent redemption rate on the codes included with the toys.

On the one hand, that provides a handful of revenue streams for Nerd Corps, and each part of the transmedia play boosts awareness of the others. On the other hand, that diversity of revenue streams involves just as many attempts to get money from an audience of children. That's a tricky situation for purveyors of children's entertainment, Faier said, especially in a mobile gaming market where some companies have been overly aggressive in monetizing kids.

"Imagine yourself as a parent of a child who loves something," Faier said. "If your child is asking to buy them something that's awesome, and you gladly do it, that's the [desired] result. If you can achieve that, then you can be proud of the revenues you're generating. It's when you start to cut the corners and try to take advantage of your audience... The morality of that is questionable, and I think parents and kids can see it. If you're in it for a quick hit with a cheesy product that's got a hook, parents know that. You're going to get one shot at it, and you won't get a second, third, or fourth with that brand."

"You can't do it in a faceless way. You have to be able to get up in the morning and say, 'Yeah, I'm a parent of a child and I'm good with this.'"

Faier offered a rule of thumb for developers concerned about where to draw the line when it comes to making money from an audience of kids.

"Is this something that I could stand in front of a large group of parents with, have them ask me the hard questions, and answer with a heartfelt response that I believe in as to why I think it's so awesome? Then I think it's great," Faier said. "You can't do it in a faceless way. You have to be able to get up in the morning and say, 'Yeah, I'm a parent of a child and I'm good with this.'"

Faier said one thing developers sometimes overlook is the timing on the first monetization pitch in an app. Any new brand needs to work on building trust with its audience, and more importantly, the parents of its audience. One sure way to prevent that trust from building is to have the parents' first exposure to the brand come in the form of an aggressive sales pitch.

"When a 7- or 8-year-old asks their parents, 'Can I get this in the game," there's a dialog between the child and the parents about that," Faier said. "An eight-year-old is better able to convince their parents to spend that money because they love the game or they're playing it a lot. Whereas if they just downloaded it, or it's a thing the parents have never heard of, they haven't seen that their kids are watching it and now they ask for $5, I think it's a tough sell."

That caution is especially relevant for transmedia properties, because a bad impression from the toys or a mobile app will impact the parents' view on anything else carrying the brand's name.

"When we launch a game related to a show, we have to think about that because we have other things we're selling, eventually," Faier said. "You want it to be coming from a place of heartfelt enjoyment.... We have to build trust for the greater good of the property."