2012: The Year Ahead in Tech

Digital Foundry on a year where triple-A gaming is in transition and how mobile technology continues to explode

We're entering uncharted territory in 2012: the beginning of the end of the current console generation, and a time of transition for both home and mobile hardware. By the end of this year we will have seen new console launches from Sony and Nintendo, another revelatory increase in the power of tablet and smartphone devices and the last big hurrah from game-makers looking to extract the last drops of performance from the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360.

First up, let's take a look at the new launches. We've already championed the cause of the PlayStation Vita - Sony's brand new handheld device, coming in February. Already available in Japan, its poor week two sales have already prompted some to write-off the console's chances, but the fact is that a launch dominated by western franchises was never going to result in record sales - especially when Nintendo has finally got its act together in terms of quality first party games for its cheaper 3DS. The fact that Japanese favourite - Monster Hunter - appeared on 3DS, not Vita, is another contributing factor to the Vita's sales shortfall.

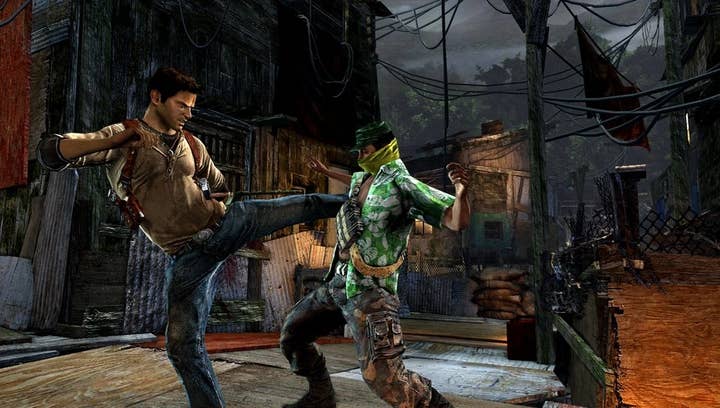

Despite that, Sony must surely be fairly satisfied with a Japanese launch where 80 per cent of the launch allocation sold through in less than two weeks, and Vita will most likely do better yet in the US and Europe where games likes Uncharted and WipEout command much more of a following. It's way too soon to write off the machine, and I can imagine it doing very well with core gamers, co-habiting and to an extent dove-tailing with the Android and iOS ecosystem. So long as PlayStation Suite delivers, it could well be the device to offer the best of both worlds - the traditional premium handheld gaming experience alongside the more bite-sized offerings of the mobile market.

From a technological standpoint, Vita is intriguing in that as the first major hardware launch from SCE since the departure of Ken Kutaragi, its hardware architecture is somewhat more conservative compared to previous efforts such as Cell, the Emotion Engine and even the custom PSP architecture. The combination of quad core PowerVR SGX543 and ARM Cortex A9 processors in a single SoC (system on chip) is entirely consistent with the development of mobile technology in general: it would be no surprise at all if Apple were to use the exact same components in its forthcoming A6 chip for iPhone 5 and iPad 3 due later this year. Sony will be relying on Vita's fixed hardware platform and the ability for devs to code directly "to the metal" for it to retain its technological edge, even when other mobile devices eventually overcome it in terms of sheer horsepower.

What interests me most about this decision to opt for more conventional hardware is that it may well have some bearing on Sony's future plans for its PlayStation 3 successor. The choice of Cell for PlayStation 3 paid off for the platform holder's internal studios, who have crafted some of the most technologically advanced games of the current gen era, but it's safe to say that Cell hasn't really paid off for multi-platform developers, with the computational power of the SPUs often used to replicate functions typically carried out on the graphics cores on PC and Xbox 360 - anti-aliasing and post-processing effects for example. With DirectX 11 so strongly positioned to dominate the next-gen landscape and the offloading of CPU tasks to GPU via DirectCompute (rather than vice-versa as we see with PS3), there's a strong argument for Sony's strategy for more conventional hardware to be extended towards its next console even if that comes at the expense of backwards compatibility with the existing catalogue of PS3 titles.

Nintendo faces an interesting challenge with the launch of Wii U later this year. What's remarkable about the console is just how little we know about its technical innards months after its initial debut at E3 2011. What we do know is that IBM is providing the CPU, while AMD offers up the graphics core. Simply through the efficiencies gained in these technologies over the past five to six years, we can expect Wii U to either be faster or cheaper to produce than the equivalent chips in the PS3 and 360 yet rumours persist that the spec has still yet to be finalised, and that the prototypes sent out to developers have exhibited heat issues. The compact form factor of the Wii U along with confirmation that the CPU at least runs on a 45nm process (just like PS3) suggests that Nintendo's console is of the same generation as the current Sony and Microsoft platforms, and that the innovation is in the wireless tablet controller.

Wii U specs strongly suggest that the console has been tailored to a multi-platform environment, but it remains to be seen how much - if at all - it exceeds the capabilities of the 360 and PS3, and how it stands to compete against forthcoming next-gen platforms. While we can see the tablet forming an integral part of Nintendo's game concepts, the question must be raised of just how much we can expect to see multi-platform developers utilising it: platform-exclusive hardware in a multi-console environment is rarely utilised to anything like its potential by anyone other than the first party developers.

Nintendo's bet on the controller rather than the core processing hardware suggests that it believes that raw power and quality of visuals are not the defining factor of next-gen gaming, or else that it wants to handle the transition to HD gaming by carving out its own path - an interesting gamble in the light of titles such as Battlefield 3, an excellent game on console, but a whole different ballgame on PC.