Talking Shop: Riot Games' Lead Designer of Social Systems

We chat with Riot Games' Jeffrey Lin about molding player behavior in League of Legends

GamesIndustry International sits down with another member of the industry to talk about what they do. Today, we're talking with Riot Games lead designer of social systems, Jeffrey Lin. Lin brings his background in psychology to Riot's immense League of Legends community. He and his team spend their days finding ways to curb player behavior without resorting to the banhammer. Prior to his time with Riot Games, Lin worked at Valve Software as an experimental psychologist. He received his Ph.D. in cognitive neuroscience from the University of Washington.

Carl 'Status' Kwoh (Producer) and I lead the player behavior team at Riot Games. On a day-to-day basis, we're constantly pushing our research efforts to better understand player behavior and then apply that research to new features or systems in League of Legends. As a development team, our mission is to ensure League of Legends has the most sportsman-like community in core competitive games.

It's surprising how insights in player behavior impact all aspects of Riot. When the team first started sketching out what we'd need we never thought we'd be developing policies and guidelines for a professional sports league; but just a few weeks ago the game designers from Team Player Behavior collaborated with our esports team to develop a new Code of Conduct for our League of Legends Championship Series. During another week, the player behavior team worked with our marketing department team to create an event celebrating the positive players of our community. Player behavior is truly a company-wide initiative.

I think that's the best part about being on Team Player Behavior: no two weeks are ever the same. We have to learn and adapt. For a team full of naturally curious scientists, that's our definition of fun.

"Player behavior is truly a company-wide initiative"

I loved games growing up. I remember beating Legend of the Mystical Ninja 2 an embarrassing number of times with my brother. I also fell in love with MMOs, from Ultima Online to Everquest. I was always quite mature for my age, but there was a thrilling moment in Ultima Online when a GM I befriended asked me online if I'd consider becoming a GM because of my accomplishments in the community. I was ecstatic! Unfortunately, I was rejected when they found out I was 13.

After that missed opportunity, I began my long academic journey and earned a Ph.D in Cognitive Neuroscience from the University of Washington. As a scientist, you're always told that your only career path involved becoming a professor and getting tenure. I did well as a young scientist, receiving funding from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute during my Ph.D, but it wasn't my true passion. I enjoyed my work, but it's difficult to see the impact of your research until years, if not decades after the initial discoveries. I was hungry to see data in action.

Near the end of my Ph.D, Mike Ambinder from Valve Software gave a talk at the University of Washington, but there was a twist: he was a Ph.D in Cognitive Psychology. He showed me that there was a demand for our skillsets in the games industry, and we connected over several lunches and brainstorm sessions about how scientists could shape games in the future. A few months later he offered me position at Valve as an experimental psychologist.

In 2011 at PAX Prime, I met some guildmates from Everquest for the first time. Though we'd played together for 15 years, this was the first time some of us met in person.

It was absurd. We had grown up together playing online games, but we rarely talked about real life - it just never came up. It turns out that our other guildmate, 'Kitae' was Christina Norman, a lead designer on the Mass Effect series, and now both 'Geeves' (Kevin) and Christina were working at Riot. They invited me for a visit, where I met Tom 'Zileas' Cadwell, and Riot's co-founders Brandon 'Ryze' Beck and Marc 'Tryndamere' Merrill.

Marc and Brandon told stories about online communities and toxic behavior-how it has always existed since the beginning of online games. They challenged me: does it have to be this way? Is there anything we can apply from psychology, cognition, or neuroscience that could make a difference?

They asked me how I would approach it, and what I would try if given a team. They mentioned Riot's 'no constraints' philosophy. I remember sitting there, thinking to myself: this was a difficult problem. We couldn't guarantee success and we'd be exploring new territory for both the game industry and academic landscape, but they wanted to try because as players they cared about the player behavior problem. I was all-in.

Getting a Ph.D isn't for everyone, but it has proven invaluable for my position. It has very little to do with raw knowledge. What's useful is the ability to critically break down problems, to design robust experiments that can derive valuable insights and then to make the decisions that merge both data and intuition.

"Having a Ph.D is like having more tools in your toolkit; you see opportunities that others may not realize exist"

For example, how does a company design an experiment to test whether a feature was more fun for a player? A lot of designers may rely on intuition and experience - and it's surprising how accurate these intuitive decisions can be - but it's even more reliable when we can use our intuition, create hypotheses, and test those hypotheses to confirm our assumptions or discover insights that can drive future decisions.

On the player behavior team, we have experts from a diverse set of fields. We have a Ph.D in Human Factors Psychology, two Masters degree holders (in Aeronautics and Bioinformatics), a Statistician, and people with backgrounds in Marketing and Education. Some of the most fascinating scientific discoveries have been from scientists that 'cross-over' into another field and apply their expert knowledge in creative ways. Having a Ph.D is like having more tools in your toolkit; you see opportunities that others may not realize exist.

The diversity of the Riot team is one of our best resources. Rioters are encouraged to take initiative and just make things happen. For example, if the player behavior team needs help from a person with clinical psychology experience, we send a blast out to the company and see who we can recruit. More often than not, someone at Riot has the experience and expertise you need.

Beyond the regular tools like Matlab, Tableau, and other software for data visualization and analyses, we have a few powerful internal tools. One example is a system we call the Microfeedback Tool. It's pretty standard at various studios to rely on forum communities or online comments to get a pulse on community sentiment of new products or features; however, forum communities are rarely representative samples of your active playerbase.

With the Microfeedback Tool, we can specify a few parameters such as 'Level 30' and 'North America' and a time period such as '24 hours.' The system than randomly samples the active playerbase using those filters, and sends them a survey question in-game over the specified time period, so you can even control for sampling across different times of the day. This tool has been invaluable, and several times revealed biases by just sampling from a forum community; in many cases, the sentiment of the active playerbase was the complete opposite of the forum community.

A typical day for me usually involves collaborations across many departments and teams at Riot. However, as a player behavior team we're currently heavily focused on an issue known as the 'Champ Select problem' in League of Legends.

In League of Legends, players start a game by being matched into a team with up to four strangers. They then have 90 seconds to discuss their strategy, and what champions and roles each player would like to play. From psychology, we know that this is a recipe for disaster and many games will begin on a sour note because arguments will erupt before the game even starts!

We recently visited MIT and Harvard to talk to some scientists who have studied cooperative behaviors, and shared some of our data and current development on the problem. Many of them pointed out the obvious difficulty of expecting trust and teamwork between strangers - with a deadline of 90 seconds - and they are not the first to see this problem. How do we incentivize cooperative, versus destructive behaviors?

This is a tough problem but by resolving time pressure and focusing on improving team chemistry before a team is formed, we're going to try and make this a better experience for players in League. We believe the end results will be interesting not just for the games industry but also for scientists across different industries studying cooperation.

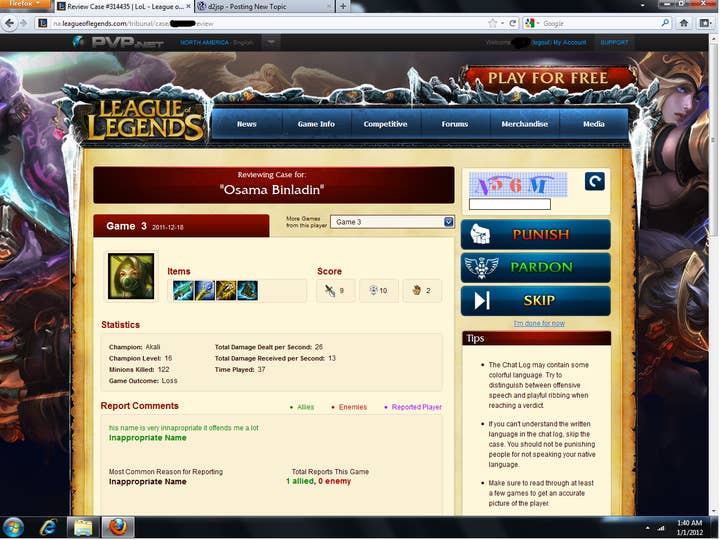

When I first started, the Tribunal System had already launched from an idea by Steve 'Pendragon' Mescon and Tom 'Zileas' Cadwell. In League of Legends, players can report each other on a variety of dimensions-both positive and negative. The Tribunal bubbles up the worst offenders in the ecosystem, and then creates a 'Tribunal case' for them. The community can then view these cases online, and vote on whether the behaviors are appropriate or not. It was a very intriguing take on player discipline, but at the time we still believed that player behavior problems stemmed from 'bad apples' that ruin the entire community.

As we conducted more research, an insight changed our entire approach to the player behavior problem. We were creating behavioral profiles for players in League of Legends, to map out toxic behaviors and see how they lived and spread in the community. What we learned was the power of context, and how context inside and outside games can twist behavior-context could create bad behaviors even in good people. What we learned was that simply banning the truly toxic players in our game didn't impact the game very much-they only accounted for about 5 percent of the total negative behaviors in the game. We needed to find a way to impact and nudge our neutral and positive players from having bad days.

"A lot of people claim that online communities are innately toxic: full of homophobia, racism, and sexism. But that just isn't true"

We started focusing on reform instead of removal. One of our recent experiments was to try a Restricted Chat Mode, where players are forced into situations with limited chat resources and have to decide between using their chat resources for cooperative behaviors, or still use them for negative behaviors. The results have been surprising, and we learned that a large number of players were self-aware of their negative outbursts: we received a ridiculous number of requests for players to opt-in to this experiment so they could get help managing their own behaviors and ultimately have better experiences online.

We are also focusing on spotlighting positive behaviors, and showing players how amazing the community actually is. A lot of people claim that online communities are innately toxic: full of homophobia, racism, and sexism. But, that just isn't true. In the Tribunal, cases that have these types of terms are among the most highly punished cases in the entire system-online communities are pretty awesome, we just need to find ways to shed the negative perceptions that weigh game culture down.

Looking back on the past year, it's clearer than ever that player behavior really is a company-wide effort. Importantly, it's also a collaborative effort with the players. Developers can't fix player behavior alone, but supporting players and providing them with the tools they need to shape their own community is how we change this culture.

As a scientist, the amount of data we have is a dream come true. It's pretty common for player behavior members to explore data, and find interesting insights on a daily basis. There are full-time analysts on the team that curate the data and categorize it in interesting ways for the player behavior team and other teams at Riot.

For example, on any given day, we can check the number of players engaging with player behavior experiments or the behavioral profiles, patterns and trajectories of players. This data can help answer questions such as: What types of players are responding best to a certain player behavior feature? What features are frustrating, and why?

Over the past year, we've really seen the League of Legends community evolve and mature. When we first launched the Tribunal, there were no guidelines or rules to help players make decisions on what behaviors were appropriate in League of Legends. However, early on you saw community social norms begin to take shape. One, players began to agree that profanity was. For example, saying "#$%^! I messed up that skill shot!" is completely acceptable to players. However, targeting profanity at someone else was considered verbal abuse or harassment. Two, players unanimously agreed that homophobic, sexist and racist comments, or death threats were unacceptable regardless of context.

Three, behavioral trends are similar across different cultures. Despite statements like, "Country A is the most negative." "Country B is the most immature." "Country C is super sportsmanlike." There are potentially more similarities than differences. Whether you are looking at reporting patterns, negative or positive behaviors, or the distribution of players in a given country, the trends look similar across the world. Sure, there are nuanced differences like what Country A considers 'verbal abuse,' is different than what Country B considers verbal abuse, but overall, the reporting patterns suggest the same prevalence of perceived verbal abuse.

It's intriguing as a scientist because it suggests that being a gamer is perhaps a culture itself. Being a gamer is something that connects us across the world, regardless of our real origins.

At Riot, we have 'hackathons' a few times a year where teams get some time to churn their creative juices and see what cool things they can create. At one of our recent hackathons, we gathered a significant number of scientists and analysts at Riot and attempted to create a Minority-Report-like predictive model. 48 hours later, only a few scientists survived, but the results were interesting. We built a model that could predict with 80 percent accuracy whether a player would eventually be punished by player behavior systems in the future based on one game of data.

But, we sat down and thought: Is this being player-focused? How does this mesh with our philosophy of collaborating with the players, and having them drive the shaping of their own community?

We could have used this model in its current form, but we didn't.

We don't face issues like these often, but as scientists, it's our responsibility to consider ethics and think about the players. This is why it's so important that we are players of League of Legends as well.

Inspired by the psychology of feedback loops, we're testing a new experiment in League of Legends called Behavior Alerts. As I mentioned earlier, a lot of toxicity in the ecosystem is a result of good or neutral players having rare outbursts or 'bad days.' The Behavior Alert system detects patterns of negative behavior or outbursts, and fires a quick ping to the player. The system comforts the player and lets them know that they are usually sportsmanlike, but seem to be having a rough patch. For neutral and positive players, this subtle nudge is often enough to get them back on track. We hope to share data from this experiment in the future, and reveal a bit more about the experimental design behind the scenes.

"As scientists, it's our responsibility to consider ethics and think about the players."

We've also been working on a feature called the Honor Initiative. As a counter to the Tribunal, players can praise each other for sportsmanlike behaviors and award a person with Honor. Positive pillars in the community are awarded ribbons and badges that they can show-off in the game. A lot of research has suggested that reinforcing positive behaviors and showing players an aspirational path to being sportsmanlike can reduce toxic behavior more than punishment can-this core philosophy is a major focus for us over the next year. We want to make it easier to be sportsmanlike, and in doing so we know players will gravitate in that direction.

Removing players is really a last resort, and we dread and hate having to remove access to a game that a player loves to play. With the emergence of free-to-play games, banning isn't even an effective discipline method because players can make new accounts and shift their toxic behaviors into the new player population. We don't believe promoting positive play and sportsmanship is a harder path for the player behavior team. In fact, it's the more inspiring path. All of the recent data suggests that a majority of the players in the community are pretty awesome people, but sometimes they just need a nudge in the right direction, or a positive goal to aspire to. Research even suggests that it can be more effective than punishment. We love the idea of celebrating sportsmanship with the players.

For each experiment, we generally have custom metrics we look at to measure efficacy. For example, we turned off cross-team chat by default for every player in the game, and forced players to opt-in to that experience. Over 70 percent of players opted-in - a surprising number given the history of opt-in programs - to the experience right after the patch, but we saw a 34.5 percent increase in positive chat in the cross-team chat channel.

We generally avoid looking only at the number of reports of toxic behavior because sometimes player behavior experiments can shine a spotlight on negative behaviors. It's not uncommon for new Tribunal features to be correlated with an increase in the number of reports, but it is most likely not due to an increase in toxic behaviors. Players are reminded about the Tribunal and the need to report toxic behaviors, so one hypothesis could be that players are now reporting behaviors they otherwise wouldn't have before.

We're generally more interested in patterns and trends as well; for example, what does the behavioral trajectory look like for a player that recently was placed in Restricted Chat Mode? Are they receiving fewer reports than before? Are they playing more games than before?

One of the early experiments the player behavior team tried was a feature called Reform Cards. When the Tribunal banned a player, we would send the player a Reform Card that outlined the exact games, chat logs, and gameplay details that led to the player's ban. On average, we saw approximately 7.8 percent more players improved their behaviors after they received a Reform Card; however, what really surprised us was the player feedback.

Numerous players wrote in and apologized for their behaviors, because they "acted that way in other games and it was fine." Other players wrote in and apologized for the words they used because they "didn't realize how offensive that word was online." These were players that weren't begging for their accounts back or requesting that their bans be lifted-they just wanted to give the team some feedback.

As we spend more and more of our time online, games and online communities become an integral part of a gamer's education on what an acceptable social norm is online and offline, and what behaviors are OK or not OK. As game developers, we are at a unique point in the evolution of online culture where we are in a position to really make a difference in online communities and games for decades to come.

There are students out there right now studying Biology, Medicine, Mathematics, Anthropology, Psychology and more who love games and want to make games, but don't have enough developers or professors telling them that that is a viable option. It is.

When I talk to students, I can't stress enough that you don't need to already be established in the industry to work on games. Grab Unity, and start prototyping a fun game or even just a fun mechanic. Grab Matlab, and crunch some data in interesting ways and show what you can do for the player behavior team or a game studio. Learn Java and make an amazing app that visualizes data in a new way for a game. Design a solution for a known player behavior problem.

Make something, and show us the passion and the brilliance. We're always looking for bright young students to lead the next generation of the player behavior team, and Riot in general.

Those looking to get into the industry can take a look at GamesIndustry International's Jobs Board.