Survival and success in India's budding games industry

SuperSike, Dropout and 99Games on the challenges and opportunities facing indie developers in the world's second biggest country

Survival has been an abiding themes for independent developers in 2015. Overwhelming competition, abundant product, fickle customers; these pressures are shared by all, a community that can feel united as much by its uncertainty as its passion.

India's independent developers fret over the very same issues, only with a few more complicating factors added to the mix. The methods by which a European or American studio might seek to raise awareness of their products - be that PR, publisher or specialist press - don't exist in India to nearly the same degree. The education system has only just started to recognise the nascent ambition of the country's aspiring talent, and so demand for skilled applicants far outstrips supply. And with only a modicum of relatively uninformed interest among VC investors, the companies that do form are often composed of graduates with the sort of resources that don't stretch very far in such a competitive environment.

"There are a lot of very, very young people in this business"

Rajesh Rao, Dhruva Interactive

"There are a lot of very, very young people in this business," says Rajesh Rao, CEO of Dhruva Interactive and chair of the NASSCOM Gaming Forum. "That requires a lot of support." And Rao isn't embellishing a single word of that assessment. According to a report released by NASSCOM, 75 per cent of the workforce in the Indian games industry is below the age of 30. Almost 60 per cent of Indian games companies operating right now were founded in 2012 or later, and almost the same proportion have fewer than ten employees. There is no shortage of passion among India's game developers, but age, experience and scale are rare commodities.

Amit Ghoyal is a shade older than most of the indie developers I meet at NASSCOM GDC, and the story of how he founded his studio, SuperSike Games, is telling. Four years ago Ghoyal and his co-founder were both working in radio, they had no training or professional experience in game development, but they were endlessly passionate players. When I ask how they learned the necessary skills for game production, he says this: "We would go up to people and ask them, 'Please, tell us how to make games.'"

It is a playful response, of course, but it carries more than just the ring of truth. SuperSike's third employee was an experienced programmer, but the whole enterprise was founded on the assumption that they would have to learn almost everything on the job. Even now, with six games listed on the product page of the SuperSike website, Ghoyal selects the work-for-hire jobs that help to keep the company afloat on the basis of how each one can help the team to learn and improve.

Even for those at university age, entering the industry with limited education and knowledge is arguably a more sensible option than formal training. Ankush Madad co-founded his studio after becoming disillusioned with the curriculum at one of India's small handful of game focused higher education courses. "My interest in gaming was from an early age," he says. "I've wanted to pursue the field for a very long time, and I thought that if I get to the best college I would probably get to where I want. It wasn't that way."

"I thought that if I get to the best college I would probably get to where I want. It wasn't that way"

Ankush Madad, Dropout Games

According to Madad, the course was entirely focused on console and PC development, two markets with very little representation in the regional games industry. NASSCOM's data indicates that 96 per cent of Indian game developers are focused on the mobile market, and yet Madad was on a course seemingly geared around exporting talent to PC and console companies elsewhere in the world. "Out of 30 or 40 people just one or two move out of India," he says. "For the rest of the people it gets very hard. We can get jobs, but we have to learn the entire thing again - about how the mobile space works."

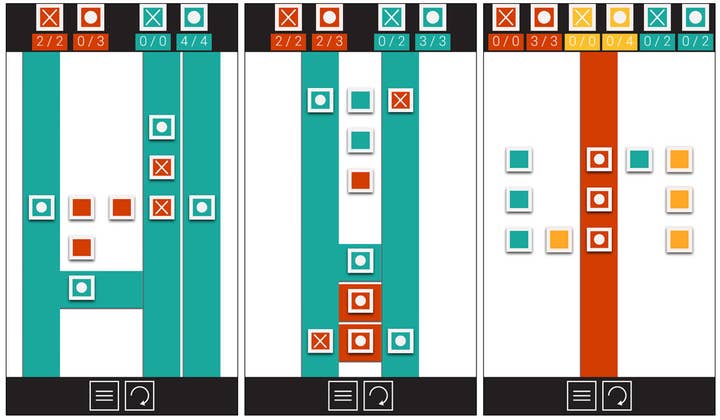

That much was abundantly clear from his first experience of an internship - at June Software, one of India's most prominent mobile developers. "I didn't know anything about how shipping for mobile works," he says. "I had to learn all of those things in the studio, and that's supposed to happen in the college. That was probably one of the bigger reasons why I decided to drop out." Madad and his classmate, Sujeet Kamar, left to form Dropout Games. Dropout's first release, UNWYND, took six months to develop. It was selected as part of an Editor's Choice feature on the App Store.

With both Ghoyal and Madad, it's clear that focusing on mobile games is a practical necessity rather than a personal preference. Though Indian mobile developers are starting from a position of relative weakness compared to those elsewhere in the world, it is still a vastly more level playing field than either console or PC. This comes through in their games, all of which are targeted at a global audience. Even SuperSike's endearingly styled cricket title, One More Run, is very much geared for the tastes and wallets of players beyond its native market.

"We're getting fantastic reviews about our game, especially from the UK and Australia," Ghoyal. "In India we do get very good reviews, but in my conversations with a lot of people, they like the game but they're not sure exactly how it will work with India from a monetisation perspective."

This touches upon a difficult problem facing the country's mobile developers. Right now, India's mobile market generates only $150 million in annual revenue from an addressable market of some 200 million smartphone users. An infrastructure for ecommerce is only just starting to develop, and so advertising is the most effective way to monetise a game. However, building a game around advertising can limit its potential to monetise in wealthier foreign markets, where in-app purchasing is more common but effective communication can be difficult. And trying to serve both masters can harm the user experience, undermining a game's commercial appeal on the most fundamental level.

"Focusing so doggedly on Indian culture and Indian context? I don't think that's necessary at all"

Amit Ghoyal, SuperSike Games

Faced with this dilemma, NASSCOM's data shows that 75 per cent of Indian game developers are making the international market their priority. For Ghoyal, this global focus can be equally effective as a domestic strategy, due to the "aspirational" nature of India's growing number of consumers.

"I think India plays what everybody else plays. Go out there and I guarantee that you will find Temple Run, you will find Candy Crush," he says. "There is a bigger chance for an Indian game to go up the charts by being an international viral hit. Some level of localisation is important - if you translate your games to Hindi or Erdu - but focusing so doggedly on Indian culture and Indian context? I don't think that's necessary at all. We would be much better off focusing on great games that everybody can play.

"My co-founder has a very simple mantra for this. We just need to survive. And if we can survive for long enough then we'll get there. The Western games industry is ahead of us, but I think we can catch up."

In adopting this strategy, of course, developers are tapping the same (admittedly huge) group of players as a vast number of other developers, most of which are more experienced and better resourced. The Indian mobile market may be small right now, but conditions for growth - credit cards, smartphones, 3G internet access, etc. - are improving at a rapid rate. When just 20 per cent of the Indian population means a market larger than Brazil there's a compelling argument for Indian studios to construct a five-year plan around the near-term potential of the national audience.

For 99Games, the Indian market is growing in importance all the time. Founded in 2008, 99Games has already released 15 games, almost all of which were developed for a global audience. The success of one of those games, Star Chef, was vital to closing a $5 million funding round in April this year, prompting the studio to expand to 37 people. However, if international appeal was key to its expansion, its view of the future is guided by domestic potential.

"India is such a big country, and there are two sets of people," says Anila Andrade, who has worked at 99Games since the beginning. "One is the masses, people who don't have high-end iPhones. They have cheaper Android phones, but they are great consumers of entertainment. On the other side you have the engineers, the doctors, and other professionals, who have a lot of money and they want the status symbols. So they want an iPhone and Candy Crush and Clash of Clans.

"So if you want to localise and culturalise your game for India, you just need to understand who you want to reach out to. The ecommerce guys are spending a lot of money to get users on board. India hasn't been a spending country, but we're getting into the habit of spending right now with purchasing online. This didn't happen two years back, and we think that will slowly transition into a habit. You'll pick up your phone and make a purchase, even if it's a small one. I personally think this will happen in the very near future, two or three years down the line."

"We're slowly getting on to designing games for the Indian consumer"

Anila Andrade, 99Games

This process will be driven by the increasing strength of India's economy in general, which, along with China, is the joint fastest-growing in the world. As the people in the first group Andrade mentions transition to the second group, they will take their powerful enthusiasm for locally produced entertainment with them. What little money most Indians do have, Andrade says, is often spent on movies and music. "Bollywood is massive. It is huge. People save their money so they can attend the first showing of a movie in the theatre."

Could the same apply to gaming? Following the release of Dhoom:3, a mobile game tied to a major Bollywood release, 99Games is certain that it will. Though it was principally monetised through advertising and brand tie-ins rather than the in-app purchases that fuel an international release like Star Chef, Dhoom:3's popularity in terms of downloads has been impossible to ignore.

"We're slowly getting on to designing games for the Indian consumer," Andrade says. "We are here, so we can understand this space better. We know that we won't be able to monetise as well, but Dhoom was an experiment, and that experiment worked very well in our favour. We intend to pursue that."