Six ways video game composers are missing out on money

Video game music is more accessible than ever before, but a lack of business knowledge among composers means money is being left on the table

You don't need to blow the dust off of your Super Nintendo or PlayStation to revisit your favourite video game soundtracks. The music of that era is more accessible now than ever before, and it has never been in greater demand. The most popular scores reach millions -- or even tens of millions -- of plays on digital platforms such as Spotify and YouTube, with publishers like Square Enix rushing to meet the demand by making their back catalogues available.

Exciting new formats have allowed music to outlive the games it was originally written for -- whether that's digital tracks from old video games such as Final Fantasy 5, The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening being rearranged for performances by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, or the soundtracks from Streets of Rage and Shinobi being remastered and released as vinyl records. Some of the world's biggest music stars -- such as Jay-Z, Childish Gambino and Wiz Khalifa -- have sampled video game music in their tracks, while music from Final Fantasy VII is played in the ad-breaks to millions of people on the Late Show with Stephen Colbert.

Royalties are usually generated in instances such as those mentioned above. However, there are a number of things that video game composers must do if they want to benefit from the usage of their music in the media.

Composers aren't set up to collect their royalties

One of the most important is to register their work with a performing rights organisation (PRO), organisations that exist to ensure composers and songwriters are paid correctly. Every time a piece of music is streamed, downloaded, broadcasted, performed or played in public, it generates performance royalties, which are collected and then distributed by the relevant PRO.

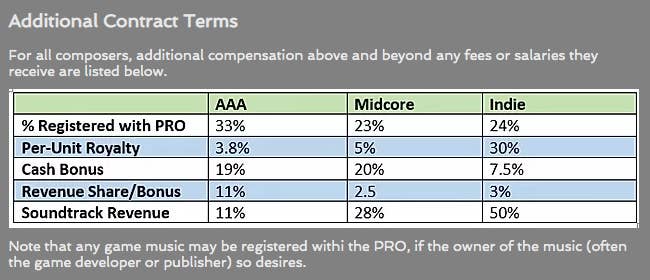

Video game composers are falling short in handling the business of their craft. According to research collected in GameSoundCon's Game Audio Industry Survey 2019, just 33% of AAA video game composers are registered with a PRO, and that number drops to 24% for indie composers. It begs the question: How much money are video game composers missing leaving on the table?

According to Brian Schmidt, game composer and executive director at GameSoundCon, it "very much depends on the game." The situation is complicated, mainly because the rules around royalty payments vary depending on whether they are mechanical or performance royalties, as well as the territory they're being issued in -- the way video game composers get paid in Europe is completely different to the US, for example.

"A composer does not have to own their music in order to receive PRO royalties," Schmidt says. "But it does mean that the contract the composer has signed with the game developer allows them to collect PRO payments and that they are entitled to 'ancillary use income' -- money received for the game's music that is [generated] outside of the game itself.

"Also important to note is that, if a composer is a regular employee of a company, any music they compose as an employee will be owned by the company. Some game companies are very good about having their employee composers register works with the PROs, while some don't allow it."

"A composer does not have to own their music in order to receive PRO royalties"

Brian Schmidt

Usually, composers will not receive any additional performance payments from a PRO when the video game they've written music for is purchased and played -- only when the music in that game is 'publicly performed', which includes digital streams on music services, appearances in traditional media and broadcast, recorded cover versions, or plays at a concert or live gig. As a result, Schmidt stresses the importance of video game composers ensuring their upfront fee reflects the full value of their work.

However, there is one exception to this rule. Since 2016, the rights management firm PRS for Music has been collecting and distributing royalties on behalf of Sony Interactive Entertainment for video games purchased through the PlayStation Network in European territories. This means video game composers that aren't registered with a PRO, but have composed music for video games sold through PSN, could be missing out on hundreds of thousands of dollars.

"If a consumer downloads a game in Europe, that is considered a 'public performance', so PRO money would be lost there," Schmidt says. "That [amount] varies a lot from game to game, but I'm aware of games where the music PRO money from EU downloads was a healthy six figures [US dollars]."

A spokesperson from PRS for Music says that it has collected in excess of over £10 million for composers and artists in the games industry to date.

Education needs to improve -- particularly among younger composers

Why have so few composers registered with a PRO? Sebastian Wolff, CEO of Materia Collective, a video game record label, music publisher and rights administrator, believes some composers struggle to see the bigger picture and value associated with their work. When musicians are in that deep moment of creating, the business of music can often be the last thing they think about.

"The idea you have to do everything yourself has become normalised, and the last thing that [composers] think about is the marketing, the business, the royalties and the planning of anything that happens beyond the game," Wolff explains. "For most creatives, especially as they're considering game audio, it's very top heavy. You put all this time and effort into creating this thing, then it goes into the game and you move onto the next project.

"I'm here like: Okay, let's talk about the next 120 years of people exploiting your intellectual property that you created. What about the soundtrack? The sheet music? The cover songs? The licensing? The royalties? The PROs? The concerts? The performances? If it bangs, what if it's put in a rhythm game?"

Video game composer Marty O'Donnell, best known for his work on the Halo series, echoes Wolff's sentiment that his peers give too little consideration to the long-term value and impact of their work. However, he reiterates that there is plenty of advice out there for composers who need it.

"I've been pushing for the Game Audio Network Guild, and that's probably one of the biggest organisations out there," he says. "They meet at the Game Developers Conference every year and do some great work. And then there's the game audio conferences featuring all of the people who are in game audio and game music. That's where the education needs to happen."

O'Donnell believes that the lack of education from video game composers on the business aspects of music is more prominent among younger composers.

"Creative people have always been taken advantage of by business people who are exploitative types"

Marty O'Donnell

"Creative people have always been taken advantage of by business people who are exploitative types," he explains. "Not that there's nothing wrong with being an exploiter -- that's how money gets made -- but creatives, as part of their DNA, don't necessarily think about the best ways to exploit their own work, so they get taken advantage of constantly.

"For these young composers it's like: 'Wow, I get to have my music on these big games -- where do I need to sign?' It's like the early days of rock 'n' roll; people who sign away everything and have nothing later on. I wish we had a system where it says 'You wanna do this? Just work within this system. Everyone will still hire you because everyone is in the same system'."

O'Donnell also stresses the importance of registering your work with the relevant PRO, as video game music can pop up in the most unlikely of places. For O'Donnell, it was finding out his music in Halo 2 and Halo Reach had appeared on Top Gear -- "All of a sudden I get a little ASCAP notification and a cheque basically saying 'Hey, we used this for Top Gear'."

As O'Donnell is registered with a PRO (ASCAP in the USA), it meant he was also able to benefit from the PRS arrangement with Sony Interactive Entertainment.

"The first Destiny was part of the deal that Sony made, so all the composers on Destiny got way more money than what we'd seen in the past -- it was a much better deal," O'Donnell says. "It wasn't 'Oh, here's this covenant dance piece that was pulled out of the Halo soundtrack and used for Top Gear'. It was literally a game music royalty that's part of the game."

Digital platforms make identifying creators difficult

Richard Jacques is a BAFTA-nominated composer of film, television and video games, an active member of The Ivors Academy's media committee, and sits on the commercial advisory group for PRS Music. He believes the additional royalties generated for video game music have become important revenue streams for not just video game composers, but video game publishers, too.

"I still collect royalty payments for much of my work -- for example my tracks on Sega's Jet Set Radio Future (Xbox), which was released nearly 20 years ago," Jacques says. "These are royalty payments that come from JASRAC, the collection society in Japan, collected and distributed via PRS for Music here in the UK, which account for everything from soundtrack sales -- both physical and digital -- to YouTube and online streaming services payments.

"Some of my very old catalogue on YouTube alone has collectively over 60 million views, which of course attracts online broadcast royalty payments, where both myself and the games publishers benefit from an additional royalty income stream. So of course royalties are an important part of how a composer or songwriter earns a living, as well as being an integral part of a music publisher's income.

"As with anything, this comes down to a commercial negotiation between all parties, often involving a composer or songwriter's agent, music publisher, music lawyer, and the games developer and publisher."

But what happens to royalties that are generated from video game music if the composer or songwriter hasn't registered their work with a PRO? These are known as "black box" royalties; unclaimed royalties that are owed to songwriters and composers but cannot be distributed, as the owners of that music cannot be traced. This can be for a number of reasons, usually due to poor metadata, which tells PROs information about the songwriters, composers and arrangers of a track.

"The music industry -- and especially the music publishing industry -- treats the different elements of the [music] copyright separately," says Chris Cooke, founder and managing director of music consultancy CMU. "There is a common distinction between the actual 'copying' element of the copyright and the 'communication' element, which applies when music is communicated over a broadcast or digital network. It's the communication bit where PRS gets involved.

"Some of my very old catalogue on YouTube alone has collectively over 60 million views"

Richard Jacques

"Once the music is being communicated over a network -- and royalties are being paid to PRS -- we end up with a data problem. How does PRS know what games have been played and what music is contained in those games? Can the games network provide that information? And if so, what information can it provide? If it's just a track title, someone has to work out what song that is, because lots of songs have the same name.

"With Spotify-style streaming services, they actually provide really good usage data when it comes to recordings. But it can still be a big challenge to work out what songs have been used and who owns those songs."

Games publishers aren't working with music publishers

Wolff believes that incorrect metadata is a big issue affecting video game composers. It is also becoming more prominent, as a growing number of publishers are rushing to upload their soundtracks to streaming services, often with incorrect data behind them.

"I think a lot of game companies are enticed by the simplicity of music distribution, but I think what most companies don't realise is they are operating as part of the broader music ecosystem," Wolff explains. "In terms of the opportunities of doing it better on the digital side, game companies need a music publisher. Hands down. And game composers need to be affiliated with a PRO or a society -- but only one that is compatible with the games industry. And this is where it gets tricky."

According to a PRS spokesperson: "Good quality music data helps us accurately pay royalties to our members. If we receive incomplete or contradictory data from music users or music makers, our job becomes much harder."

Video game publishers aren't music publishers, Wolff says, so it can often be difficult for PRS to get the data they need in order to correctly pay composers. Many game publishers have never heard of cue sheets, which contain metadata and are used by PROs to track the use of music.

"So what happens in a scenario where there's no cue sheets, there's no PRO affiliation, the works are never registered, they don't have International Standard Musical Work Codes?" Wolff asks. "That money either sits around in an escrow account or, more likely -- especially with the passage of the Music Modernisation Act in the US -- that money gets distributed based on market share every two years, and Katy Perry gets the money."

Composers are not taking legal advice on contracts

As well as registering their work with a PRO, everyone that has spoken for this story recommends that video game composers should consult professional advice from music and legal experts before signing any contracts related to their work.

"Firstly, always take the advice of a music copyright lawyer, since this will protect the rights of the composer or songwriter, especially if it is their first time working in the games industry," Jacques says. "The lawyer will also ensure that the game developer and publisher will have the rights they need for the game to be released. Also, there are different laws in different territories relating to copyright, so be sure to check in which territory the contract is originating from.

"There are some incredibly talented indie game developers out there, which is a good entry point into the industry [for composers]. These developers often have small development budgets until they hopefully get their titles picked up by a major publisher, so a composer or songwriter should ensure that they are protected if they agree to do the creative work for a small fee -- that they can be fairly compensated further down the line and share in the game's success."

The Game Audio Industry Survey 2019 found that 98% of AAA composers do not fully own their music, compared to 53% of indie video game composers. Both Jacques and Schmidt agree that these business practices aren't displays of corporate greed -- more just a way of working that may need reviewing given the asset of video game music.

"A game company wanting to own the music they commission for a game isn't necessarily some big, evil thing"

Brian Schmidt

"A game company wanting to own the music they commission for a game isn't necessarily some big, evil thing," says Schmidt. "You can imagine that the publisher of a big hit game wouldn't want to see the game's music appearing in a competing game, a movie that has nothing to do with the game, or a bathroom tissue commercial."

Jacques adds: "In the games industry, it is in my opinion more a lack of understanding than a corporate grab of peoples' rights. The games industry, especially with regard to contracts and publishing agreements, has historically evolved out of software development contracts from Silicon Valley in the '80s, so some of these contract templates and clauses have little or no relevance to a composer or songwriter, especially if they are unpublished.

"Smaller developers and indie publishers often don't know what music rights they need to release the game versus the rights they want to acquire."

The music industry isn't paying enough attention

While the games industry has a lot of catching up to do regarding music rights for composers, it's worth noting that the growth in video games can be a minefield for the music industry too.

"The continued growth of gamers live streaming, not to mention the esports market, poses a number of interesting music licensing questions," Chris Cooke suggests. "Are those streaming platforms and live events being properly licensed for the music they use? And if and when they are, are the composers of the music featured in the live streaming or booming through the sound systems at esport events actually seeing the money? As with any commercial innovation that uses music, everyone in the music industry is playing catch up."

With the size of the audience that games are now reaching, Sebastian Wolff believes it's important for both the music industry and the video game industry to work with each other as they inevitably move closer together. A strong working relationship will ultimately be mutually beneficial.

"When you consider the market traction and exposure the video game world has in terms of esports -- whether it's broadcast or streaming -- Let's Plays, or other consumption... that also means exposure to the music, and that's [far more exposure] then any top 40," he explains.

"I think the music industry is, for the most part, fearful of giving up the control of the context in which music is consumed. The idea that you can have an audiovisual work that exists by someone who is not part of the music industry -- someone that doesn't understand two copyrights, has never heard of a PRO, and doesn't have a record label - now they get to create and sell music?

"It's terrifying [for the music industry] -- the music is in a context that they have no control over."