Risk, reward and the road ahead for mobile games

Agent Alice marks a new level of ambition in production and marketing for Wooga, but did that extra investment lead to a larger return?

The scale and diversity of the mobile market defies simple analysis. The number of available games is now so vast that the failure of a large proportion of them is basically inevitable. Developers can earn anything between $1000 and $100 million a month from making those games, but then those companies can have anywhere between a couple of employees and several hundred. A dismal failure for one studio could fund three or four new projects at another.

When you focus on the bigger companies it is far more simple. Once headcount passes a certain threshold it becomes necessary to create or sustain several hits every year, to cover overheads, pay the wage bill, and provide ballast for any possible rough patches ahead. Newzoo's analysis of the App Store in June this year showed just how quickly the average monthly revenue drops outside of the top 20 grossing games. Outside of the top 100 even a team of just three or four people might struggle to both make a living and invest in a new project. With 250 people on the payroll, though, it's reasonable to assumed that an extended spell in the top 50 is now the minimum expected from a major new release.

"Agent Alice was our most ambitious game in terms of scope, pure production value and production effort"

This is roughly the size of Wooga, the German mobile developer that hit the big time with Diamond Dash in 2012 and Jelly Splash in 2013. Wooga is a hits-driven company in a hits-driven business, employing a production model that blends free-wheeling experimentation with merciless culling. Wooga's development teams will create 40 prototypes in any given year, with a goal of yielding two genuine hits over the same period. One wall in its brightly painted Berlin office is covered with row after row of plaques, each signifying a different game. A few of them are still going now, but the wall also chronicles those that were cancelled after a poor start, and even those that never made it to market at all. For Jens Begemann, the company's co-founder and CEO, this curious mixture of fame and shame is intended to be a reminder to Wooga's employees of the nature of the mobile market.

"We want them to know, 'Your time is very valuable. Use it to work on the best thing,'" he says. "The hits in mobile are so huge these days. They can pay for all the experiments."

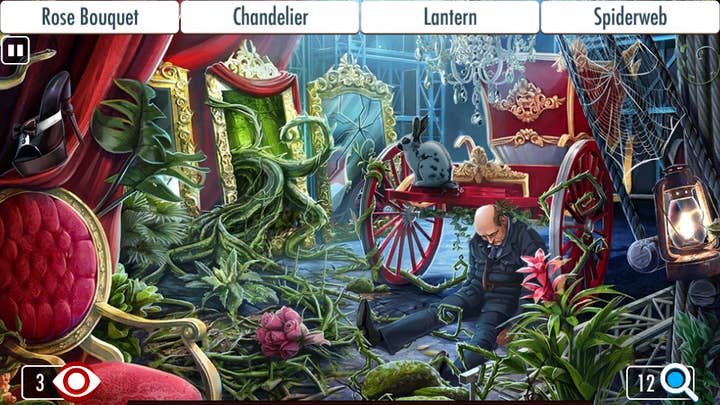

In Wooga's estimation, Agent Alice has that kind of potential. It is the company's attempt to take the hidden-object game, a genre popularised on 20-inch PC monitors, and make it sing on both 10-inch tablets and 4-inch smartphones. A small team worked on prototypes for six months to resolve the technical issues around that transition, and those conclusions formed the basis for what, in Begemann's view, is among the most ambitious projects in the company's history.

"You can have ambition on multiple levels," he says. "I think it was our most ambitious game in terms of scope, pure production value and production effort. We've had games before with a very similar size internal team; the internal team in the end was about 20 or 25, which for many of our new games at launch is not so uncommon. But we had 50 people externally, across three continents, creating artwork for us. So in that regard definitely the most ambitious.

"We spent forever discussing what we could do to avoid making so much content. What can we avoid? In the end, the conclusion was simple: if people want content, you have to give it to them. And if you have millions of users, even if just a fraction of them pay, you can also pay all of the salaries of the people involved. Then, it works."

The hidden-object game is a single-player genre, and Wooga identified high production values as the main hook to bring users back episode after episode. The problem is that this approach to content requires a major investment of resources upfront, and still more after launch to ensure that new episodes reach the same standard. This kind of investment may be what's required to stand out in such a saturated market, and one where so much of the money goes to so few of the competing parties. Nevertheless, making a bet like Agent Alice requires a huge amount of confidence in your own ability to execute.

"The hits in mobile are so huge these days. They can pay for all the experiments"

Of course, when it comes to a product launch the need for confidence becomes less relevant as the size of the marketing budget increases. The dawn of the iPhone era offered a relatively brief window in which developers could build a large audience through little more than word-of-mouth recommendations and organic virality. However, as FlowPlay's Derrick Morton highlighted at Casual Connect USA recently, the costs associated with acquiring users are now virtually the same as the revenue those users are likely to generate in many key territories. Such fine margins would be difficult in any marketplace, but in one as crowded as mobile gaming they undermine the potential impact of quality on commercial success. A good product is still essential, of course, but that extra investment raises every other metric, too: bigger budgets demand larger audiences demand more marketing.

"This is a game that only works at scale," Begemann says. "We have all of this content effort: more than 20 people internally, 50 externally, and localisation, so in total that's 70 or 80 salaries to pay. There's all of this ambition, and we're working on content that will be in the game in half a year. All of these things. To pay back those content costs you need high revenue, and to get those revenues you need a high user-base, and to get a high user-base marketing is the key component.

"When you run a company with big teams that's what you should do."

A few years ago, mobile games seemed to be the perfect antidote to the worst practices of the console retail market: the swollen budgets, the costly advertising campaigns, the opulent launch events, all without a significant increase in revenue to balance the scale. Every publisher and developer with an eye on the top of the charts had to operate in the same conditions, and a great many of them failed to keep up. Mobile companies are now racing towards that point, and far more quickly than their console predecessors. Supercell and Machine Zone recently paid for hugely expensive Superbowl ads, and LoopMe's Stephen Upstone believes annual marketing budgets for the biggest mobile companies will soon reach hundreds of millions of dollars.

Along those same lines, Agent Alice represents a first for Wooga. "Agent Alice is the first team we did a real launch of a game," Begemann says. "In the past we just put out a game and see what happens. This time it was orchestrated. We could have ramped it up more slowly, but we felt that by concentrating it into one week we'd get more effect.

"Because of the very intense competition it can't just be about word of mouth any more. It's about using traditional forms of marketing"

"Overall, the market for mobile games is growing, and there are hundreds of thousands of games out there. However, all of the growth is within the top 1 per cent, even a fraction of the top 1 per cent. Because of that very intense competition, it can't just be about word of mouth any more. It's about using traditional forms of marketing, too, in a similar you would for any consumer good."

Week-long launch periods jammed with events for press and consumers were commonplace among free-spending console publishers. Just before the market shift that contributed to, for example, THQ's demise, the money spent on high-impact marketing was often difficult to comprehend. I recall one press event in which dozens of journalists from across Europe and North America were collected at an airfield in Kent and flown in genuine World War II bomber planes for a day touring the beaches and cemeteries of Normandy. Then it was back to a truly luxurious hotel in a chic French coastal town, surroundings that redefined my understanding of "five star" accommodation. The actual work - playing the game and talking to the developers - happened the following day, in a huge stately mansion set amid lush green fields. On the ride back to Kent, our vintage bombers were escorted by showboating Spitfires.

That wasn't for Call of Duty. It was for a real-time strategy PC game, a genre with a limited audience on a platform yet to be reinvigorated by Steam. It seems absurd now - indeed, it was absurd - but that excess is not where you start; it's where you end up. Lavish spending in the name of promoting console and PC games was motivated by similar pressures to those at play in the mobile market right now. The cost of making games had increased far quicker than the people that would pay for them, and so investing money on shouting louder and with more clarity became a part of the process.

Of course, mobile has a long way to travel before it reaches that point, and Wooga is far from the most profligate player in the market. Agent Alice is, after all, a first for the company in that respect. And while I'd bet folding money that it won't be a last, according to Begemann the week-long shotgun blast of marketing, media and launches yielded immediate results. "Almost everywhere in the Western world it was the number one game on Google Play and the App Store, for a week," he says. "In the end, you get more back on every dollar spent than if you spread that money out over a longer time."

At this point, it's only right to mention that this conversation with Begemann took place at the end of April, around six weeks after the concentrated blitz of Agent Alice's launch week. I was struck, at the time, by the degree to which Wooga's strategy differed from the one evident in the timeline of failed and successful products covering that office wall. With so many resources dedicated to its development, it seemed to me that Agent Alice was never going to be allowed to join the ambiguous ranks of the unreleased, nor was it going to be allowed to launch quietly to, as Begemann put it, "see what happens." Agent Alice was a new approach for a market that changed irrevocably since Diamond Dash and Jelly Splash. Within a few months, the end result of all the enthusiasm and endeavour and investment would become clear.

"All of the growth in mobile is within the top 1 per cent, even a fraction of the top 1 per cent"

And here we are. Based on App Annie's data, Agent Alice reached a peak of 98th on the US App Store top-grossing chart on March 3, less than a week after it launched. It hasn't been near the top 200 since the end of that month. On the US Google Play store it peaked at 78th around March 9, before entering a shallow decline from which it has never recovered. European territories like Germany and the UK yielded slightly higher chart positions on both app stores in the game's early weeks, but the pattern of decline is much the same as in the US. This is also true of the download charts, where, just as Begemann said, Agent Alice started at the top of the pile in most major territories, but even with spikes from new content drops it hasn't returned to even the top 150 App Store downloads in the US, Germany or the UK since the middle of April.

Is this the performance expected from a game crafted with such care and, from the impression I was given, such great expense? I doubt it, but it's also difficult to escape the sense that Agent Alice's lavish production values and substantial marketing budget should have made more of a difference, even in a market as apparently fickle as mobile.

That, though, is the trap, and the same trap that the screenwriter William Goldman warned against when he famously observed that, in Hollywood, "Nobody knows anything." As budgets climb, marketing spend becomes more prevalent and the risks become harder to bear, we may discover that the same is true of mobile games.