Trimming The Fat: How and Why Game Design Must Change

Game design has become clumsy and bloated - it's time to shake things up

The traditional games industry has reached a dangerous point. Retail sales are down for the fourth year in a row (software sales for 2012 were down 22 percent from 2011). Worse, the number of games has dropped; the total SKUs across all platforms dropped by 29 percent. The top games are still making a profit, but more and more games aren't. Publishers are producing fewer titles and relying on sequels to proven hits in order to reduce risk, but that in itself is risky in the long run. We're already seeing that Call of Duty sales peaked in 2010. When you rely on fewer titles, any stumbles become more dangerous. What happens when you're down to depending on a few big franchises for your profits, and one of them doesn't deliver for the year? Disaster.

One response is to expand into other areas like social, mobile, and free-to-play, and put more emphasis on digital distribution and various forms of purely digital revenue. All of the traditional publishers are doing that to a greater or lesser degree, but the majority of their sales still come from discs in boxes sold at retail stores. The next generation of consoles may have more digital content than ever, but the majority of their software revenue will still be from discs in boxes for years to come.

Is there a way to introduce more new IP, take some chances on innovative games, and reduce risk? Possibly, and game design is the key.

"What happens when you're down to depending on a few big franchises for your profits, and one of them doesn't deliver for the year? Disaster.

It all comes down to design, in the end. Designers have become used to designing to the form dictated by retail sales, and they have to break out of that mold when the realities of the marketplace change. This is happening in music, video, and writing. Albums are no longer shaping how artists create music, nor are their tracks limited to the length that can fit on an analog vinyl single. Video is no longer confined to the two-hour movie or the one-hour drama, and we're seeing a lot of innovation in form, style and content on Internet-distributed video. The novel's length used to be dictated by the word count that would fit in a few price points and page lengths in a standard trim size. Similarly, game designs have been bounded by the retail pricing of games and the amount of space available on the media, and by the perceived need to provide a certain number of hours of gameplay for the retail price.

Digital distribution has removed those restrictions. Price points can be at any level; length of play is no longer set. We're seeing great innovation among games distributed digitally, first with indie games on the PC, with games on XBLA and PSN, and the explosion of games on mobile platforms. Those games have their own restrictions due to download size and the specifics of their platforms, and designers for traditional titles should be learning some things from them.

The answer to the industry's problems lies in redesigning game design to suit the demands of the current and future market. There are several steps that can be taken to reduce the risks and raise the chances for success.

First, don't treat every title as if it were going to be the next AAA blockbuster by giving it a two-year development time (or more) and a $50 million budget. Sure, sure, the sequels to your hit products deserve the big treatment; the next Call of Duty needs to have a big budget. Look at Halo 4; Microsoft spent hugely on it, and it's paying off. But that same effort on a new IP? You're asking for trouble.

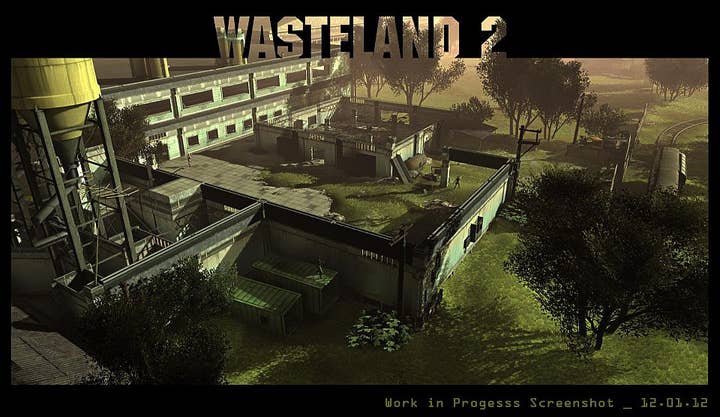

What can a publisher do with that $50 million? How about funding ten $5 million games that are on the level of some of the recent Kickstarter phenomena, like Obsidian's Project Eternity or InXile's Wasteland II? Use existing technology; don't push the graphic envelope. Leave off the voice acting. Don't reinvent an entire game system or game engine. Don't figure on including both multiplayer and single player; pick one mode and do it well. Adjust the scope of the design so it's doable in 12 months with a reasonable team size. The idea is to prove the market for the idea and the IP.

EA had a good idea a few years ago, when it tried to create a number of new IPs. The initiative floundered because the company tried to do it using the old process, which doomed it to failure. A new, innovative idea is too risky for a multi-year, $50 million plus project.

Chris Roberts is approaching it sanely. He has a grand vision of a huge space MMO in Star Citizen, but he's figured out a design that will allow him to build it in salable pieces. So he can build it without an immense budget at the start. And if the first piece or two is not a big enough success to fund the rest of it, he can stop working on the next massive pieces and save that money. Maybe it'll do well enough to fund continued content development; if not, that could be shut down, too. But he should be able to do all this with only a minor downside risk, and huge upside potential if he succeeds in making a hit.

Only there won't be a publisher sharing in that upside. Because they don't offer anything he needs. Money? A handful of investors and crowdfunding is enough, thanks. Technology? Nah, he can do that himself. Servers and back-end support? Amazon or others will cheerfully sell that in whatever size you need. Marketing? If you've got a name already, and a little bit of help, you don't need a big marketing department. If publishers don't begin to follow this path, developers will be happy to do it for them, as the growing number of Kickstarter projects demonstrates.

Traditional games have become bloated with too much that isn't really vital to the gameplay. Sure, those lengthy cinematic intros are cool, but how often do you watch them? Once. How much did that cost to make? Millions, in some cases. Maybe it's a proper marketing expense, but don't build it into the game budget.

Sometimes games are just bloated, period. Gran Turismo 5 took more than 5 years to develop at a cost of over $80 million, and includes over 1,000 cars and 71 tracks. This is just ridiculous; has anyone ever used more than a small fraction of those cars? Get the game engine done in whatever time it takes, sure, but the game needn't ship with more than a few dozen cars and perhaps a dozen tracks. Sell more tracks, more cars, more customizations later, once the game is out there making money.

"Traditional games have become bloated with too much that isn't really vital to the gameplay"

Mobile games have shown how to strip gameplay down to the essential elements. Social games have refined the onboarding process to a minimal time, rather than making players spend hours learning the controls. Do you really need a whole new graphics engine? A brand-new character creation system? A completely new set of algorithms for combat, and a new set of weapons?

If there's one thing Minecraft should have taught us, it's that pushing the graphic envelope isn't always necessary to have a hit game. You don't have to look like an 8-bit game, either; the screen shots from Project Eternity look very nice. Do we really need voice-overs? Nope, that sure doesn't affect the gameplay at all, but it can add a lot of time and a lot of cost to a game budget.

Now obviously a stripped down title isn't worthy of a $60 price point... so don't charge $60 for it. Try $20, or $15. We know publishers can still make money even at retail stores with that pricing, if they could convince the retailers to carry such a low-priced SKU. That may not be as impossible as it might seem, given some clever marketing. A special end-cap display, some branding for the innovative games under a special label, a clever promotion - it's all in how you set expectations for the customers.

Perhaps these titles might debut as digital distribution only, and only jump into retail when they've proven their audience. Out of ten titles, maybe only one or two gather a following. Then the publisher can fund more content for those successful titles, give it a deluxe treatment and put it out into retail with a much lower risk.

This development strategy is the same one successfully used by King.com for casual games: Develop many ideas with a small team and a low budget and test them on an audience. Take the successful ones, give them a special treatment and roll them out big time. Rinse, lather, repeat. This strategy took King.com to the #2 Facebook game publisher in just 18 months from their first Facebook game introduction.

We know that some of the best designers around are working at some of the biggest companies, but they only get to do one project every few years. And when they do, those designs are constrained by the publisher's risks. We therefore see fewer and fewer games, with less innovation. That's both annoying to us as players and frightening to investors. Why have all the major publishers' share prices been languishing for years? Because investors aren't convinced they have the potential to create breakout hits on a regular basis. With good reason, as publishers place fewer and fewer development bets with less innovation attached.

There are certainly other strategies that can be followed to get more games, and more creative games, from the big publishers. Let's see some attempts, before the big publishers become smaller the hard way. New publishers are growing rapidly with online games (like Riot and Wargaming.com), and social games (like Kabam) and mobile games (Rovio, Gree, DeNA, Supercell and others). The old-school publishers need to redesign their design processes or risk getting outplayed.