Pure vision vs. player feedback | 10 Years Ago This Month

People trying to do something different have always struggled with the question of whether the customer is always right

The games industry moves pretty fast, and there's a tendency for all involved to look constantly to what's next without so much worrying about what came before. That said, even an industry so entrenched in the now can learn from its past. So to refresh our collective memory and perhaps offer some perspective on our field's history, GamesIndustry.biz runs this monthly feature highlighting happenings in gaming from exactly a decade ago.

Sometimes this column lets us look back on a problem facing the industry and see who was right, who was wrong, and how different a situation seems with the benefit of hindsight.

Other times it's a reminder that some problems are just intractable and the games industry will be probably be grappling with them in different ways for as long as people play games. This is one of those other times.

In August of 2013, the topic of discussion was the relationship between the creator and the audience, and what role the latter should play in shaping the former's creations.

We'll start with Schell Games' Jesse Schell, who told us in an interview that there's one mistake successful game companies always make, "and that mistake is listening to their customers."

Customers, Schell argued, will always want the advantages offered by new technologies, but they don't want it from the existing market leader. At the time, the example he cited was Microsoft, which had recently announced digital restrictions for the Xbox One, and then backtracked on them in light of fan backlash.

"Microsoft said, 'We're going to be Steam. You like Steam, don't you?' And we all said, 'No, we hate that. We hate you.'Jesse Schell

As Schell described it, "Basically, Microsoft said, 'We're going to be Steam. You like Steam, don't you?' And we all said, 'No, we hate that. We hate you. You're an idiot to do that.'

"They came out and said, 'We're gonna do this new thing.' And the customers said, 'No, we don't want that, we hate that' - even though it's what they really want and what they will ultimately buy. So now Microsoft has had to say they won't do all that stuff, but someone will."

While nobody copied Microsoft's restrictions like locking physical discs to a single user account to thwart second-hand sales or mandating daily online check-ins, the rapid shift of the last decade toward digital distribution and always-connected experiences shows that the vast majority of the gaming public has accepted a more connected world with less actual ownership over the games they buy and no right of first sale.

Schell suggested listening to customers will steer you wrong because "the hardcore folks always want the same thing: 'We want exactly what you gave us before, but it has to be completely different.'"

But what about Nintendo? If there's a company known for a willingness to do something different in good times or bad, it has to be Nintendo. The Wii, the Nintendo DS, the Wii U, the 3DS, the Switch… all of them introducing unexpected new functionality consumers didn't even know they wanted (or didn't even know they didn't want, in the case of the Wii U GamePad and 3DS glasses-free stereoscopic 3D).

Surely we can agree Nintendo is a company that doesn't make the mistake of listening to anybody but its own visionary employees when it charts its blue ocean voyages. But even if we did agree on that, the people actually running the show over there probably would not.

"Nintendo developers are extremely insatiable when it comes to whether what they make resonates with customers or not," Nintendo president Satoru Iwata was quoted saying in August of 2013. "They'll do anything to achieve it. Both (Shigeru) Miyamoto and I repeatedly say, 'It's not like we are making pieces of art, the point is to make a product that resonates with and is accepted by customers.'"

Iwata added, "Creating is like an expression of egoism. People with a strong energy to create something have a 'this is the strength I believe is right' sort of confidence to start from. Their standpoint is that this is the right thing to do, so this must be what's good for the customer as well. But the final goal of a product is to resonate with and be accepted by people. You can't just force your way through. By saying, 'The point is to be accepted,' I mean, if you go to a customer with your idea and you realize they don't understand it, it's more important that they do and you should shift your idea."

Getting back to the Xbox 180, Codemasters co-founder and Kwalee CEO David Darling took a more dismissive approach to the fan backlash, saying Microsoft's problem was actually that it didn't push the Xbox One's connected vision hard enough.

"They've let the market pull them back but I think that was a mistake."David Darling

"I don't think they should have had a physical drive on Xbox One - it's like having a dead body handcuffed to you," Darling said. "It's dragging along this dead body and it's going to slow them down. They've let the market pull them back but I think that was a mistake."

Unfortunately, we'll never know what would have happened if the Xbox One had been handcuffed to a single dead body instead of two (don't forget Kinect, which was packed in and helped inflate the system's price $100 over the PS4). But Darling's suggestion later in the interview that Apple TV could make consoles obsolete has me not wanting to rely too much on his predictive abilities.

Meanwhile, original Xbox project co-founder and former Microsoft employee Ed Fries was "impressed" not just by Microsoft caving under the pressure, but by how quickly it did so.

"They clearly are responsive to feedback, and I think that's great," Fries said. "We all make products for customers, and it's important that we listen to our customers when they have things to say to us."

The interesting thing to me is that whether you would consider yourself part of Team User Feedback or Team Creative/Strategic Vision, they are both defensible positions, and the downsides of taking either to their logical extreme are readily apparent.

Listening to customers is a great thing for a company to do, both in terms of being a pragmatic route to success and creating work that fulfills user expectations.

But at the same time, making games is a creative endeavor and mob rule isn't much of a replacement for a well-thought-out production where disparate elements combine and reinforce one another to form a cohesive whole. "Too many cooks," and all that.

We essentially never see either the Team User Feedback or Team Artistic Vision approaches in their purest forms

Pursuing an artistic vision is likewise a noble goal for ambitious creators looking to explore new creative territory and push the medium forward. But people in every creative discipline tend to benefit richly from constructive criticism, both from peers and the audience alike, and the auteur mindset is less noble when it results in hundreds of developers throwing away years of their lives building disposable monuments to a narcissistic schmuck.

And let's not even get into the moral modifiers that get tacked on when you consider the jobs that might be cut or the companies that might go under when you chase a vision with no care for what people want, or the Venn diagram overlap between the aforementioned auteurs and abusive workplaces.

While we essentially never see either the Team User Feedback or Team Artistic Vision approaches in their purest forms, I do think the past few generations have seen a significant shift in the industry downplaying the importance of creative vision in favor of whatever the audience wants, and that's something Fries was clear about even a decade ago.

"If you think about games, we used to spend three years making games and stick them in a box, and people liked them or they didn't like them," Fries said. "Now it's much more direct feedback from customers. We test things a lot, see what's working and what isn't working and the launch is the beginning of the process. I'm talking more about free-to-play games now - you're basically developing it with your customers. We have a much more interactive relationship with our customers. If people aren't happy they let you know, and they can cause trouble for you."

That quote touches on two big drivers of this shift. First, there's the abundance of feedback channels available to players now. We've gone from needing to track down a mailing address and sending a letter with a stamp on it via snail mail to being able to reach developers through official channels on forums and social media, and even unofficial channels via doxed devs' personal contact info. Progress!

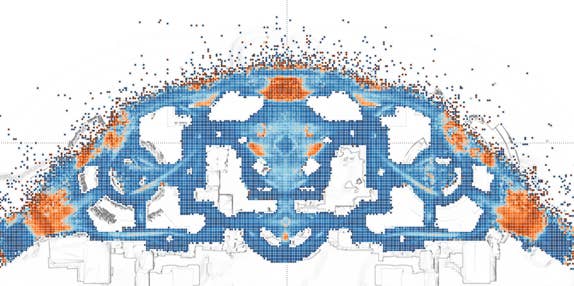

The other big changes include analytics and user behavior tracking, as players are not just voting with their wallets but also unwittingly giving feedback through the features they use and when, where in the levels they die, what color buttons they click on, and so on.

While I'll stop short of calling these things unmitigated positives, both of those advancements offer plenty of tangible benefits to developers that can help make their games "better," whether you define that word as "more closely realizing creators' artistic ambitions" or "making a truckload of money." And neither of those advances is going to disappear from the developers' toolbox anytime soon.

But I do think there are some disadvantages here when compared to the "put it in a box, chuck it over the wall and hope players like it" approach.

"Creative vision" has always been just one factor for developers to consider, balanced against others. But audience feedback and analytics and market research have multiplied greatly over the years, while the creative vision behind a project is still just one thing being weighed against increasingly heavier stacks of information.

These new feedback channels and the abundance of new data they offer have plenty of benefits, certainly, but I worry they would also undermine confidence in pursuing any kind of a vision that runs counter to the data.

And as much as rank-and-file creatives might be frustrated by giving up on parts of the vision because of the analytics or the audience feedback or "the realities of the market," the executives who ultimately decide whether to go with or against those things aren't always thrilled by the calls they make either.

Like in August of 2013, when PopCap CEO Dave Roberts was defending the decision to make Plants vs. Zombies 2 free-to-play by citing the game's installed base and the dominance of free-to-play on the top grossing mobile charts, which at the time had free-to-play games taking up the top 70-90 positions.

"That's the sad truth," Roberts said. "People have decided that free-to-play is a better way for them to monetise. And, some of the purists would argue that the industry has made them do that. Can you do it in a way that preserves what we believe is the great game experience and customer experience? We hope so. We think so."

If Roberts found that truth sad in 2013, it must be worth ugly crying over today. We checked with mobile market intelligence firm Data.ai to confirm our suspicions about how dominant free-to-play is on the charts these days and they told us the top 100 grossing games globally for July 2023 consisted of 99 free-to-play games and a lone premium title: Minecraft Pocket, "and that's usually the case." (Frankly, I'm impressed Minecraft Pocket can crack the Top 100 on a regular basis.)

Roberts' apparent misgivings around free-to-play were somewhat mirrored by EA Games executive VP Patrick Söderlund talking about why EA was experimenting with second screen features and social functionality.

"If you look at how [the smartphone] affected your life, how Facebook affected your life, I can't watch TV without using [a smartphone] five times during a movie," Söderlund said. "It's ridiculous, but that's what it is, and everyone does that."

Is it weird to see people whose livelihoods depend on these things talk about them with resignation and almost loathing? As a games journalist, I can confidently say "not at all." But I would hope it's weird for normal people.

Regardless, I do find it a bit weird to see people so ready to not just refer to outside trends or audience reaction when making decisions, but to seemingly defer to them.

Whether you're talking about creative decisions (weapon degradation in Breath of the Wild, the save system and time restrictions in Dead Rising, tank controls in Resident Evil) or more commercial ones (Nintendo's pursuit of non-traditional audiences, Sega abandoning hardware), there are ample industry success stories that presumably required ignoring early audience feedback, what the metrics were saying about the situation, or possibly both.

Personally, I'm pretty skeptical of overreliance on feedback and metrics, and that's largely informed by what I've seen happen in my own field over the past few decades.

Journalists have always taken a bit of a cynical stance toward audience interests. "If it bleeds, it leads" was a phrase long before I ever considered a career in journalism, and the suggestion that the comics section is the most-read part of the newspaper obviously goes back at least to the days when people read actual newspapers.

But then the internet came along and gave outlets the data to back up their cynicism. And not just reader surveys to find out what they read (or in many cases, the high-minded coverage they wanted us to believe they read), but actual cold hard numbers to show how many people clicked on a story, and how long they spent on the page.

We could work out how much any given story made in advertising. We could see how much experienced staff backed by resources would move the needle (marginally) compared to an SEO operation given those same resources instead (much more).

We had social media engagement metrics to help explain whether traffic was bring driven by a very good story (yay!), a very divisive story (yay!), or a Twitter dogpile where we were being dunked into the Earth's mantle over a very embarrassing and error-ridden story that should never have been published (still yay, somehow!).

All this data hasn't really helped journalists better serve their readers because it more directly helps outlets optimize around what makes money

But as you may have noticed, all this data hasn't really helped journalists better serve their readers because it more directly helps outlets optimize around what makes money. And unless you're an outlet with zero concern for the barrier between editorial and sales, journalists do not make money. (Just ask journalists.)

If you want a direct example of how that sort of thing can translate into games, I would point you to Zynga vice president Gemma Doyle's GDC session on managing whales, where she talked about the concrete returns she could promise to fund her white glove service for high spenders, and how metrics made a compelling argument for management divying up its limited resources.

"To add another 20 engineers to [a successful] game is a very significant investment for an unknown as to whether those features will give you the ROI that you need," Doyle said in her session. "Whereas we're coming in with very solid results to say, 'Here's the projections. Based on what we've done, we've had three years success. Here's the linear increase we expect to see, and we'll get it immediately when we add those heads."

It was rare enough for journalists and developers to be able to pursue and create the work they believed needed to be done before. But in the face of management armed with data about what the audience wants – data that will be believed above and beyond what the audience says it wants, it's harder for the people actually producing the thing at the heart of the operation to get any say in the matter at all.

Of course, this isn't happening in a vacuum. Audience habits and desires are always changing, and we really do need to meet them halfway, if not a little further. For journalists, if nobody reads the so-called good stuff, it's not doing much good and we need to think about how it could change to better serve readers, with keeping the lights on being a nice bonus on the side. But at a certain point, the data started doing more to constrain the work than enable it.

So whether you're talking about game developers or journalists, I worry the abundance of data and feedback we've come to rely on is being sold as empowering people to create their best work, but in practice does as much or more to distort or de-fang it, to make it consumable when it needs to be challenging, to turn what many pursue as a calling into just another commodity.

What Else Happened in August of 2013

● Steve Ballmer announced his retirement from Microsoft. Shares in the company rose 9% upon the news.

● Microsoft continued its Xbox One reversals, confirming that using the Kinect camera would not be mandatory for Xbox One, even though the thing came packed in with every system.

● Ouya had a bad ad. How bad was it? We thought it was newsworthy in its badness.

● John Carmack joined Oculus, saying, "The dream of VR has been simmering in the background for decades, but now, the people and technologies are finally aligning to allow it to reach the potential we imagined."

Carmack left the company last December, saying he had mixed feelings about his time there.

On the positive side, Meta Quest 2 was a lot of what he wanted to see when he joined Oculus. On the other, he lamented the inefficiency of the company, saying, "I have never been able to kill stupid things before they cause damage."

He left to work in the field of artificial general intelligence, which is possibly the worst place to put someone with a demonstrated inability to kill stupid things before they cause damage.

● Sony and Microsoft used Gamescom to build hype for the next-gen, with the former announcing PS4's launch dates while Microsoft laid out a launch day slate of 23 Xbox One games.

● Sony Online Entertainment announced EverQuest Next, its user-generated content-driven attempt to get players to both make and buy the game while SOE cashed checks. It's a dream many have tried but only a few have pulled off.

This particular version of the dream ended with Daybreak (which SOE changed its name to upon splitting from Sony) cancelling EverQuest Next a little more than two years later, with company president Russell Shanks explaining, "Unfortunately, as we put together the pieces, we found that it wasn't fun."

Wow, the metaverse trend really was just blowing billions to speedrun through everything you could have learned from watching MMOs over the past couple decades, huh?

Good Call, Bad Call

BAD CALL: I was happy to see that Jesse Schell interview that got us started in the section above, because Schell and his Crystal Ball Society have been good fodder for this column before. He didn't disappoint with an entry in one of our favorite genres of Bad Call here, the old standby "consoles are doomed."

"E3 convinced me that they are going to be struggling," Schell said of the soon-to-launch Xbox One and PS4. "I haven't seen anything that made me think, 'Yeah, you're gonna get that market share back.' I'm convinced that all [of the consoles] are going to have a gradually eroding market share over the coming years. Because tablets are going to be eating their lunch more and more, and other platforms are going to start to take off and catch fire."

A decade down the road, we know that consoles have thrived in the decade since, and even the solidly industry-trailing Microsoft is boasting about doing twice the business it was doing during the Xbox 360 era.

We also know that tablets did not consume ever-more market share from consoles, as market research firm Gartner put worldwide tablet sales at 195 million in 2013, and just 137 million in 2022, with that number expected to decline another 3% this year.

That's pretty unspectacular as far as Bad Calls go, and I'm not sure if I would even mention it if not for a much better call Schell made with his next breath.

GOOD CALL: "The thing that's going to make the biggest difference in the next four years, say, is that someone's going to come out with a great gaming tablet - a really grade-A tablet for games. Exactly what that means I don't know; I suspect it has a separate hand controller, and I'm sure that it connects up to your TV no problem. I don't know who's going to make that, but it doesn't smell like Microsoft, Sony or… well, maybe, who knows what Nintendo has up its sleeve, right?" – Schell basically describes the Nintendo Switch, from its features to its release date. Switch would launch with about half a year remaining in Schell's four-year window.

BAD CALL: Nintendo president Satoru Iwata ruled out working on non-Nintendo platforms, telling CVG, "If I was to take responsibility for the company for just the next one or two years, and if I was not concerned about the long-term future of Nintendo at all, it might make sense for us to provide our important franchises for other platforms, and then we might be able to gain some short-term profit. However, I'm really responsible for the long-term future of Nintendo as well, so I would never think about providing our precious resources for other platforms at all."

Two years of underwhelming financials and increasing pressure later, Iwata and Nintendo announced that the company struck a partnership with DeNA to bring its famous franchises to mobile. Keen to pre-empt any speculation that the company was abandoning its traditional business, Nintendo simultaneously announced its next console, code-named NX. It would later be named the Switch, and has done far more to turn the company's fortunes around than its modest mobile business.

GOOD CALL: Iwata again, this time saying that the Wii U's price wasn't the reason for its disappointing sales. And we know this was a Good Call because Nintendo cut the price anyway two weeks later, and it didn't really fix the problem.

GOOD CALL: Wedbush analyst Michael Pachter acknowledged that the writing was on the wall for GameStop as a physical retailer in a digital world, but believed it could cling to life for a decade longer, which it has done.

BAD CALL: In the same story, Pachter said the company would produce earnings per share growth "for much of the next decade." It managed to grow earnings per share for just two years before the declines set in, and it has posted a loss per share for five years running.

BAD CALL: Activision Publishing head Eric Hirshberg said the thing about the industry that had him most excited was second-screen gaming because the PS4 and Xbox One connected to smartphones and tablets more easily.

"You'll see a lot of creativity and a lot of energy coming from developers with the next-gen in this area," Hirshberg said.

We certainly saw some energy from publishers to convince people second-screen was a thing, but this is still a Bad Call. Second screen gaming is basically dead unless you extend the meaning to include keeping a tab on your smartphone open to a guide or walkthrough to help answer questions about Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, Baldur's Gate 3 and the like.

GOOD BUT ENTIRELY UNHEEDED CALL: Koch Media co-founder Klemens Kundratitz told us it's good to stay grounded and not overextend yourself.

"I think it's important to follow your own special positioning and doing things which we are able to achieve and not trying to reach for goals that are not realistic," he said. "Being too ambitious, as we have seen with THQ for example, is not always a good thing."

As luck would have it, Kundratitz has had a front row seat to see that same lesson once again with THQ.

Koch Media would be acquired by THQ Nordic in 2018 as part of an ambitious acquisition blitz that has seen the company acquire scores of studios in recent years (and change its name to Embracer Group), but also left it deeply in debt and in need of a significant restructuring. Koch itself (now rebranded as Plaion) is also going through a restructuring, but has said it is unrelated to the Embracer woes.