Pokémon's strategy is cross-generational

By balancing nostalgia for parents with appeal to children, Nintendo hopes to create gaming's first cross-generational franchise

The problem with the children's games or media markets is that for the most part, they're transient. Children grow up, leave behind the things they once loved, and the next cohort of children find new toys, games or stories to obsess over.

Only a handful of truly beloved things manage to pass from cohort to cohort and from generation to generation - a hallowed list of cultural touchstones that have survived the test of decades and decades of children's approval. Disney's animated movies make the grade, as do a handful of superheroes like Spider-Man and Batman. Harry Potter looks like it might join this pantheon, though the jury's still somewhat out on whether its continued success is down to adults reliving their childhood obsession or new children discovering the franchise for the first time.

"Detective Pikachu is quite distinct from previous Pokémon films, which were laser-focused on kids and would have offered little to the long-suffering parents dragged to the cinema to see them"

If we talk about media for very small children, there are far more evergreen things to be found - from Dr. Seuss to a famous caterpillar who I'm pretty certain has an eating disorder - but once you hit the age when children are making their own media decisions through the tyranny of pester power, they get far more fickle and trends have a far shorter horizon.

Getting a franchise of some kind to the point where it's genuinely evergreen with kids - enjoyed by new cohorts of children in perpetuity - is practically a license to print money, which is why lots of companies want to do it and lots of executives daydream about it. Disney, the most powerful entertainment company in the world both commercially and culturally, was built on its ability to generate this kind of property. Get one of these in your back pocket, and your company is essentially set for generations.

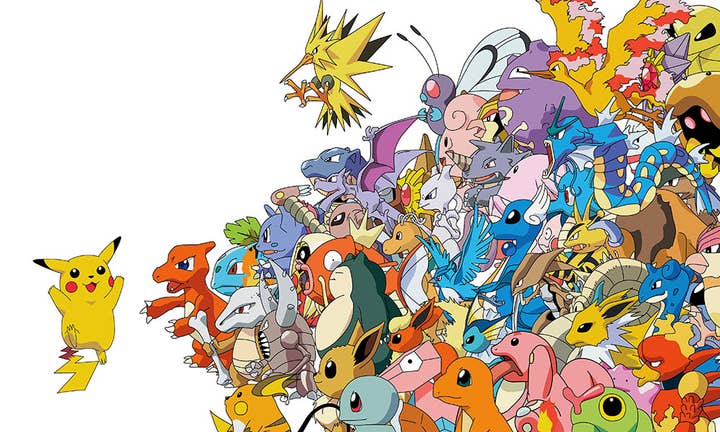

The games industry has one franchise that's getting close to that goal - or at least, has managed to land boots on the same continent as that goal - and that's Pokémon. It's early days yet and in some regards Pokémon is only facing its first real test; that's a strange thing to say about a 22-year-old franchise (game franchises are aged in dog years, after all) but bear in mind that Spider-Man has been swinging around New York since 1962 and Disney's first classic animated movie launched in 1937. On these timescales, the Pokémon franchise is so young that even Professor Oak would have misgivings about irresponsibly advising it to leave home and train dangerous animals to fight each other.

This week saw two major developments for the Pokémon franchise - the release of a trailer for the Detective Pikachu movie, a fairly major Hollywood effort based (with major liberties) on the franchise, and the arrival of reviews for the new Pokémon Let's Go games on Switch. The former has been divisive, though the majority of opinion seems to fall in favour of the trailer looking like a pretty fun movie; the latter has almost uniformly garnered praise.

What's more important, I think, is how these two things fit with a broader strategy around Pokémon that Nintendo and its partners have been executing for the past few years; a strategy that's laser-focused on turning Pokémon into an evergreen franchise that can hop from generation to generation, just as Disney movies or Spider-Man do.

"[The test is] seeing whether the enthusiasm of parents can be transmitted to their children, turning them in turn into genuine fans of Pokémon rather than just serving as an excuse for a nostalgia trip"

The key to this strategy is a recognition that the early twenties are an important formative time for a franchise. Many of the people who originally played Pokémon way back in the late 1990s are in their mid-thirties now (some older - the first Pokémon games did notably well with mid to late teen audiences too). Many of them have children of their own, and some of those children are hitting the age group Pokémon games are aimed at. This is the test; seeing whether the enthusiasm of those adults can be transmitted fully and effectively to their children, turning them in turn into genuine fans of Pokémon rather than just serving as an excuse for a parental nostalgia trip. In essence, these evergreen children's franchises survive and thrive by turning the parents themselves into willing and effective brand ambassadors.

As such, Pokémon's strategy has moved away from what it did for its first two decades - appealing directly and solely to children and teens - and started branching out in directions that aim to do something much more tricky, namely retaining that appeal while also building in a big enough dose of nostalgia and adult appeal to keep parents engaged.

Pokémon Go was the first really major step in that direction, and its success remains the cornerstone of the strategy. The game's huge appeal across generations likely took the company by surprise a little, but that shouldn't mask the success of the core idea - that a parent could take their child out for a walk or to the park and catch Pokémon together.

Pokémon Go is explicitly designed as a game that works perfectly as an experience for parents and children together - even as one that fits nicely with the perennial parental admonishment to go and play outside. Notably, Pokémon Go was also developed externally to Nintendo (and The Pokémon Company); bringing on outside expertise was a new step but is one the company seems to see as central to its ambitions for the franchise.

How does this tie in with the new Pokémon film and games we saw this week? Well, consider this - on the one hand, the firm has just confirmed that it's releasing a pretty high-profile Hollywood movie which has a clear "Who Framed Roger Rabbit?" vibe to it and seems perfectly designed to offer parents a movie they can enjoy along with their kids. That's quite distinct from previous Pokémon films, which were laser-focused on kids and would have offered little to the long-suffering parents dragged to the cinema to see them; Detective Pikachu looks quite set to work for adults and children alike, quite possibly offering quite different entertainment to both generations (assuming it's done well - fingers crossed).

On the other hand, the big Pokémon game release for the holiday season is a console game which quite deliberately harks back to the original games - a carefully calculated nostalgia trip for parents who played Red and Blue all the way back in the nineties.

None of this is a mistake and much of it is direct from the Disney playbook. Disney has been masterful at creating experiences that exploit these two approaches - entertainment that works on two different levels for children and adults, along with carefully pitched nostalgia trips designed to make adults long to share their childhood favourites with their own children. The jewel in the crown of this strategy is the Disney theme parks themselves, which have effectively become fixed and timeless expressions of childhood wonder that parents often long to share with their children as much as the children themselves long to go, but the broader strategy can be seen across the company's properties - from Disney Animation through Pixar to Marvel Studios.

References to Nintendo being the "Disney of games" have been thrown around for years, but it's never quite been true; their enormous library of IP and huge quality back catalogue is a big deal, but despite Nintendo's venerable age - it was making playing cards before Walt Disney was even born - it's never quite captured the cross-generational appeal that made Disney into such a juggernaut. Now, with Nintendo taking confident steps in establishing that kind of appeal for Pokémon - not to mention the first of its theme parks coming online in Osaka in a couple of years, which is another distinctly "parent and child enjoying together" kind of venture that aims squarely at the long-term strategy of Disney - I'd argue that they're getting genuinely close to that ideal for the first time.