Nintendo's February showcase proves that nostalgia is big business | Opinion

As the generation who embraced PlayStation in their teens hit middle age, new leases of life for the games of the past are a smart strategy

The first Nintendo Direct presentation for 2022 -- and arguably the first major showcase event for any platform this year -- seems to have been largely well-received by fans, but it's hard to deny that there was a slightly unusual tone to the announcements.

While new games did feature, a great deal of Nintendo's focus in this presentation was backwards-looking, a nostalgia-fuelled parade of re-releases, remakes, and reinvigorations of past glories. One could argue pretty convincingly that this is nothing new for Nintendo, a company that has always been very much at home with repackaging its past, but not so long ago we might have expected a showcase event that used re-releases of games and content from decades past as its tentpoles to be the subject of derision, not rapt anticipation.

What's changed, perhaps, is the audience, whose rising appetite for nostalgia and its willingness to pay for older titles is signalling something of a shift in the industry overall.

It turns out that old games really are both valued and valuable. It just takes the right approach and the right platform to make them profitable all over again

The key here is a demographic shift that's seeing the first generation of consumers for whom video games were truly a mass-market pursuit -- the people who were teens when the PlayStation and PS2 were in their prime -- entering their mid-thirties and forties.

This happened for the SNES / Mega Drive generation some years ago, of course, and it spurred a wave of interest in retro or faux-retro titles harking back to that era. But those systems were never a part of mainstream youth and young adult culture in the way that the PS1 and PS2 were, and the wave of nostalgia-fuelled consumption that's accompanying the middle age of people who were teens when the PS1 ruled the roost is correspondingly much larger.

For a company like Nintendo (and many of its Japanese peers), this effect is further boosted by the fact that the late 1990s was the era in which Japanese pop culture started to become immensely popular among teenagers, meaning that games in this era began to embrace and promote themselves as being distinctly Japanese, rather than reskinning or rebranding themselves to hide that aspect from a less adventurous Western audience.

This interest from consumers in the games of their misspent youth is a huge opportunity for a company like Nintendo, which has both an enviable archive of games and IP stretching back over this time period, and a console platform that's damned near perfect for enjoying re-releases of 1990s games that look dreadful on a full-size modern TV but are ideally suited to the smaller screen of the Switch. As I mentioned above, this isn't new territory for Nintendo, to the extent that the company has often been accused in the past of rehashing the same games over and over in the past.

However, that criticism has never really been fair; while Nintendo has never been shy of selling its back catalogue to consumers on new platforms every few years, it has also mastered the art of using very well-established characters and IPs in order to sell a pretty wide variety of innovative games across many genres, meaning that the "Ugh, another Mario game" eye-roll reaction has often missed the point that Mario's face frequently helps to sell fresh and innovative games that might struggle to find an audience without a familiar IP as a hook.

This week's Nintendo Direct, however, was not an example of that. Aside from a few bits of news about new games (albeit mostly sequels, of course), this was a genuine wall-to-wall nostalgia-fest -- one which was laser-focused on the rosy nostalgia, and the purse-strings, of gamers of a certain age. The announcements of re-releases or remakes of beloved (if arguably somewhat niche) titles like Chrono Cross, Advance Wars, Earthbound, Front Mission, and so on are the most obvious example of wallowing in nostalgia, but even the announcements related to modern games were reaching back through the decades.

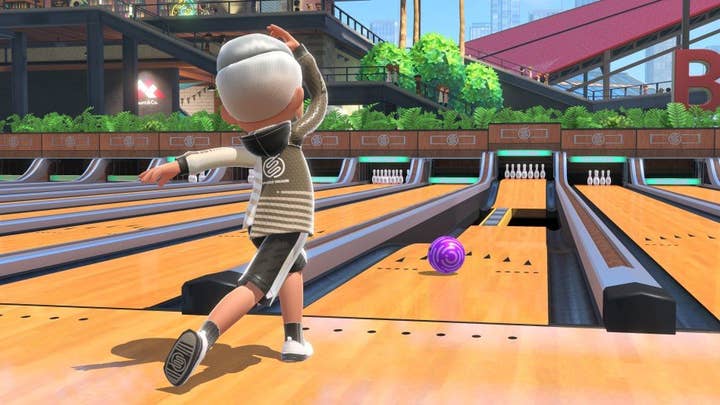

Switch Sports is fine-tuned to tweak your nostalgia for Christmas 2006, when Wii Sports was both totally ubiquitous and utterly impossible to get your hands on

The 48 DLC tracks announced for Mario Kart 8 are all remasters of tracks from classic Mario Kart games, while Switch Sports' announcement was fine-tuned to tweak your nostalgia for Christmas 2006, when Wii Sports was simultaneously totally ubiquitous and utterly impossible to get your hands on. Did you remember that Wii Sports is now old enough to be in high school? I didn't, and if that fact gives you the same twinge of depression I felt when I looked it up, you're probably right in the middle of Nintendo's target demographic for this stuff, just like I am.

The point here isn't to sneer at Nintendo for dusting down old titles in this way; on the contrary, I think this is a very clear example of how nostalgia for older titles, largely on the part of older gamers, has become one of the industry's most effective and evergreen sources of content and income, and is driving a set of strategies that are being employed by a wide range of companies, not just Nintendo.

Focusing on this nostalgic demographic is a smart strategy, in fact; the audience that's really nostalgic for these kinds of games are mostly in their mid-thirties through to their forties at this point, which is an absolutely perfect sweet spot for cashing in on nostalgia.

That same demographic group is also the main target audience for immensely successful remakes of PlayStation-era classics like Resident Evil 2 and 3 or Final Fantasy 7, all of which sold many millions of copies -- over five million for RE3, around ten million for RE2, and probably somewhere between those figures for FF7R, with these remakes' sales numbers sitting pretty comfortably alongside the sales for brand new major instalments in their respective series.

It's conjecture based on a bunch of anecdotal data, but I'd wager that this demographic is also the primary target audience for Microsoft's tremendously successful Game Pass right now, with older gamers being far, far more likely to go starry-eyed at the prospect of returning to Xbox and Xbox 360 era classics on the service than their younger counterparts.

The success currently being enjoyed by older games -- whether they're remastered, remade, or just made available on modern hardware where consumers would formerly have had to scour retro stores to find a copy -- upturns certain tenets of industry wisdom. One of those is the long-standing complaint that games lack a "long tail" comparable to the ongoing revenues for things like movies, TV shows and so on; in light of these recent successes, it turns out that old games really are both valued and valuable, and it just takes the right approach and the right platform to make them profitable all over again.

Another is the importance of backwards compatibility, which was honestly a bit of a side-show in the console wars for decades; platform holders made much of their ability to offer backwards compatibility when it suited them (generally using it as a stick to beat a competitor that couldn't offer similar functionality), but there was little evidence that it was something that really mattered much to consumers making buying decisions. That has turned on its head to some extent as well, with Game Pass' library of older software being a genuinely huge selling point for the new Xbox consoles. If Sony can offer similar functionality on PS5 down the line, filling out a storefront or subscription service with games from the pre-PS4 generations, it'll undoubtedly become a major USP for that platform as well.

This wave of re-releases and remakes is great in some regards, but it'll do no good for the industry's addiction to franchises, interminable sequels, and reboots

The response to this week's Nintendo Direct also shows pretty clearly that it's not always the most obvious games that get the audience excited. Resident Evil 2 and Final Fantasy 7 were easy to point out as worthwhile targets for a hugely expensive remaking process: they were among the stand-out classics of the PlayStation era, after all (one wonders if Konami's execs will ever stop their Scarface-style huffing of the gacha-driven revenues from their trite mobile games for long enough to notice that they're sitting on a pretty large number of the remaining PS1-era titles whose remakes would be a similar license to print money).

Titles like Chrono Cross, Front Mission and Earthbound are all extremely well-regarded, but a far cry from being commercial juggernauts like Resident Evil or Final Fantasy -- I'd argue that they're generating significant buzz in the wake of the Nintendo Direct announcement not so much because people actually played them back in the day, but because the hugely positive reputations they've garnered since then make people are excited to see what they missed.

There are multiple reasons why this audience of older gamers with deep-rooted nostalgia for the games of the 1990s and 2000s has become so commercially desirable. Some of them are obvious -- this age group is an audience that generally has a decent chunk of disposable income, for example. They do have a tendency to be more careful in purchasing decisions than younger audiences, but this actually bodes well for things like video games which are generally seen as good value for money in terms of entertainment expenditures.

Cynically, it helps that companies already know which IPs this audience likes, because banking on an IP with a built-in reservoir of nostalgia and goodwill is always going to be less risky than trying to do something new. It's worth bearing in mind that while this wave of nostalgic re-releases and remakes is great in some regards, it's going to do no good for the industry's deep-rooted addiction to franchises, interminable sequels, and reboots.

There's a secondary reason why this audience is attractive, though, and it's to do with establishing the games business' most beloved IPs as generational -- a crucial step on the way from having a great, successful franchise like Mario or Final Fantasy, to having a genuinely world-conquering one like Star Wars or Spider-Man.

Many of the gamers who are most delighted with this new lease of life on the games they loved in their youth are parents, and feeding their nostalgia has the welcome side-effect of introducing games and IPs to a whole new generation of future consumers, thus ensuring its longevity and a whole new cycle of nostalgia.

Just ask Disney how well this works; you can characterise everything Disney does across its franchises (Disney's own movies and properties, Star Wars, Marvel) as being part of a machine that's designed to drive this kind of cross-generational engagement.

This multi-generational strategy is now at the heart of what Nintendo is doing with its IP and its platform -- and while Nintendo is far from being alone in that approach, watching a Nintendo Direct presentation that feels curiously laser-focused on 40-year-olds with twinges of 1990s nostalgia is a dramatic demonstration of how far down that path it has come.