Next-gen consoles need next-gen business models

It's time for a revolutionary change in the game business or consoles will be left behind

Console game sales (at retail) are once again down by more than 20 percent over last year. The high point of console game sales was 2008, and the industry has steadily declined since then. Sales of downloadable content (DLC) have certainly offset some of that decline, but overall the top console game companies have been struggling against this market trend. The top games are selling more copies than ever, but the game that does merely OK (and makes a profit) is an endangered species. Fewer games are being produced for consoles as publishers strive to make every game profitable, and avoid potential losers.

Many observers put the blame for slower sales on the fact that current consoles have reached six or seven years in the market, well past the usual expiration date of console hardware generations (typically four or five years). Late in the console cycle, sales always decline, they say. True enough, but some analysts note the growth in mobile, social and online games may be taking away some of the console gamers, or at least part of their attention and their money.

The hopes of console game publishers now rest on the next console generation. The Wii U launching this week will, in this view, begin the revival on console game sales. New games, with new game play features and better graphics, will boost sales. That hope is missing a key part of the changes that have taken place in the game industry over the past several years. To understand this more fully, a review of game industry history is in order.

"Console games are falling further and further behind games on other platforms when it comes to business models"

The console game business began in the 1970s and grew to the amazing level of $2.3 billion in sales by 1983, mostly on the strength of Atari. By 1985, total industry revenues had dropped more than 97 percent to around $100 million. What happened? The great crash was caused by a wave of crummy games (with the E.T. Cartridge as the prime example) flooding retailers. People stopped buying console games, retailers returned huge numbers of games, and the industry collapsed. It wasn't until Nintendo managed to solve some of the key issues causing the crash that the industry was revived, led by the success of the Nintendo Entertainment System.

The key issue that Nintendo identified behind the crash was the lack of quality control. It wasn't just that Atari's games were bad. The rise of Activision and other companies creating games for Atari's consoles meant that there were large numbers of games fighting for shelf space, and no assurances that any of them were any good. Many of them weren't, and consumers were overwhelmed by the bad games. Nintendo solved that problem by assuring retailers that Nintendo would restrict the number of games released, and through a strict licensing process ensure that all games met a quality standard.

The process proved successful, and Nintendo led the rebirth of the console game business. Every other successful manufacturer of game consoles since has followed the general pattern set by Nintendo. The console manufacturer requires game developers to buy development systems (often very expensive), go through a qualification process, and have all titles approved by the console manufacturer before they can be sold for the platform. Publishers selling games in retail stores had to pay a fee per game to the console manufacturer, ranging from $7 to $12 per unit. The process just to become a certified developer can take months, and games can spend weeks or months being approved.

Recently, with the advent of digital distribution on consoles, this has changed somewhat for downloadable games. Developers don't have to jump through quite the same hoops, though there's still an approval process that can take weeks or months to get through, with no assurance of approval. The rules for indie games are even looser on Xbox Live Arcade but there are still plenty of restrictions. Sony and Nintendo have numerous hoops to jump through as well.

The experience of Fez is instructive. “Every developer gets to release one patch for free as part of their inclusion on XBLA, but subsequent patches are expensive - certification costs tens of thousands of dollars,” Rob Fahey pointed out in an article on Fez's troubles. The difficult and sheer expense of Microsoft's process meant developer Polytron felt it necessary to skip putting out a patch for Fez, which was corrupting save games for a number of users. Microsoft's process encouraged a poorer game experience for consumers.

"Part of the success of mobile, social, and online games has to be attributed to the freewheeling environment, where developers are free to choose the business model, implement any sort of design, and make changes or add new content as often as they like"

Meanwhile, mobile games go through a minimal process and wait perhaps a few days to appear in the store. Developers can post changes and new content as often as they wish with no restrictions. Charge any price you like, or none at all. There are some restrictions, but most developers easily avoid problems in getting games into the stores. Games on Facebook have some process to get through, but nothing compared to a console game. Online games have no process at all to deal with, other than technical issues.

Riot Games, whose massively successful free-to-play online game League of Legends has created an audience of tens of millions of gamers (and hundreds of millions in revenue), can't see itself doing a version of the game for consoles. “The infrastructure of consoles is so different; we couldn't push out constant updates and changes, or have that direct communication and feedback that is so crucial to our success,” said Riot president Marc Merrill.

Free-to-play games have already taken over the mobile game market, accounting for the majority of the top-grossing games on smartphones and tablets. MMOs are almost all free-to-play these days; if EA can't succeed with Star Wars: The Old Republic as a subscription game, it's pretty clear that model isn't viable for new MMOs. The free-to-play online game has become a huge business in Asia both for PCs and for mobile platforms, leading to the development of multiple billion-dollar companies across China, Korea and Japan.

Consoles are just beginning to experiment with the concept of free-to-play games. Sony has allowed some free-to-play games on the PS3, and Microsoft is now beginning that trial as well. Nintendo may consider it some day. Console games are falling further and further behind games on other platforms when it comes to business models.

Part of the success of mobile, social, and online games has to be attributed to the freewheeling environment, where developers are free to choose the business model, implement any sort of design, and make changes or add new content as often as they like. Customers are learning from mobile, social and online games that good games don't have to cost $60 up front. They're also learning that some games can respond to what users like and don't like, add new content and options every week or even more often.

Console gamers are, surveys show, playing mobile, social and online games too. That means the variety of games and their business models on other platforms hasn't escaped their notice. Games as a service, with a stream of new content and updates, is becoming more and more popular on a variety of platforms. Consoles risk getting left behind in the overall marketplace if they cannot offer the full range of compelling game experiences that players can find on other platforms.

"What if Nintendo threw open the doors to developers and allowed anyone to develop games for the 3DS or the Wii U for a $99 license fee?"

The social aspects of games are more important than ever, with connections to Twitter and Facebook becoming a key part of EA's plan to transform its game franchises into 24/7/365 gaming experiences. Ubisoft is also linking key franchises on different platforms through Facebook. Console manufacturers seem reluctant to allow connections to other social networks, preferring a walled garden for their users. Cross-platform play is clearly something publishers would love to have, but console makers want to keep gamers confined to their platform.

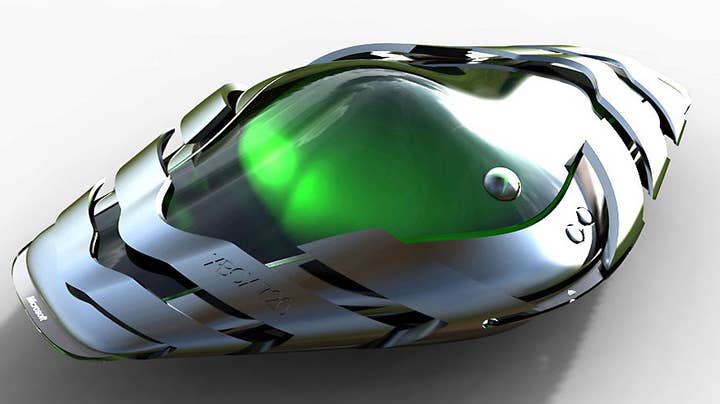

Right now Microsoft and Sony are placing the final touches on the technology to put into their new consoles, and exactly how to price them for the increasingly complex gaming marketplace. Nintendo's new console is about to arrive, hoping to carve out a substantial audience before Sony and Microsoft launch their new consoles. It seems strange that a tremendous effort has gone into engineering new consoles, yet console business models are changing very slowly.

There's a huge competitive advantage waiting to be unlocked for the console maker that dares to unleash its business from the shackles of the past. What if Sony made the only console that had League of Legends? Or if Microsoft's new console was the only console where you could play World of Tanks, World of Warplanes and World of Warships? What if Nintendo threw open the doors to developers and allowed anyone to develop games for the 3DS or the Wii U for a $99 license fee?

Sure, some execs could have palpitations considering all the things that could go wrong. Copyright violations! Improper content for kids! Pornography! Rampant ESRB ratings violations! Cats and dogs, living together! Mass hysteria! It sounds apocalyptic, but Apple and Google have managed to thrive despite having a minimal process in place. Standards and copyright laws may get violated, but those are quickly corrected.

Ah, but if you throw the doors wide open, you might end up with the App Store problem of hundreds of thousands of games, many of them repetitive or boring or just plain bad. True enough, but Apple and Google seem to be surviving that, too. App discovery is a big problem, and getting bigger for mobile games, but there are solutions being worked on. (Amazon has dealt for years with the problem of finding the right product amongst millions, and has developed some good tools for that.)

The console makers don't have to go the full distance that Apple and Google have gone towards openness. Steps can be taken in that direction, though, like allowing unlimited updates for content or patches, without charging burdensome fees. New ways of monetizing games should be encouraged, not forbidden. How about ad-supported games? Or a premium games channel (which is where PSN is doing some interesting experimentation with PlayStation Plus and the rotating library of free games)? At least free up the publishers to try a greater variety of price points; let the publishers find out the optimal price points for their games. And for cryin' out loud, Microsoft, take Microsoft Points out in the woods near Redmond and give it a quiet burial in between Clippy and Microsoft BOB. Just price your products in the local currency, like every other online store does.

"There's no technical reason why consoles have to be burdened with cumbersome business practices; they are now just because that's the way it's been for decades"

The point here is that gamers expect more from games these days than just a one-time purchase. Declining sales of full-priced games (those that aren't named Halo 4 or Call of Duty or FIFA) points to a desire for better value, or perhaps lower prices to start with. Much of the game industry's resource in time and money is now headed towards platforms with fewer restrictions on creativity in game design, implementation, and business models than current consoles. Publishers like EA and Activision aren't crowing about huge investments in new consoles the way they used to before a new console generation; instead they're talking about the growth in their digital revenue and their new mobile game divisions.

There's no technical reason why consoles have to be burdened with cumbersome business practices; they are now just because that's the way it's been for decades. Those practices slow development time, restrict the number and variety of games that appear, and generally make doing business with a console manufacturer less attractive than creating for other platforms that lack those restrictions. Consoles used to counter that by offering a much larger audience than PC games could. That's no longer true, looking at the tens of millions that play the top mobile, social and online games. Those markets are bigger at the high end than the best console games, and generate more profitability for a lower investment. That's just looking at the current console generation; is there anyone that thinks the next generation of consoles will sell more units than the current generation has sold?

Changes in business practices don't need to wait on manufacturing, or the right moment before the holiday selling season. The earlier business practices are changed, the better it will be for next-gen consoles, because that will mean developers have more time to absorb the changes and make games to suit them. Sure, the console makers will want to keep their new hardware secret until the launch, so they won't reveal the details to every developer in advance. That's fine, test-drive the changes on the big publishers you already work with. Then, when you're ready to tell the world about the new console, you can also tell the world that anyone can develop for it.

It's time for a revolution in console business practices, and that may have a greater impact on the number and quality of games (and the size of the audience) than an increase in processing power or rendering capability. Differences in polygon count and frame rate from today's consoles to next-gen consoles may be hard to see unless you're a hardcore gamer looking closely, but anyone can spot the difference between $60 up front and free-to-play.