Microsoft hypes new games console, doesn't talk about games | 10 Years Ago This Month

Microsoft's big unveiling took an audience hungry for the future of games and force-fed them entertainment of the past

The games industry moves pretty fast, and there's a tendency for all involved to look constantly to what's next without so much worrying about what came before. That said, even an industry so entrenched in the now can learn from its past. So to refresh our collective memory and perhaps offer some perspective on our field's history, GamesIndustry.biz runs this monthly feature highlighting happenings in gaming from exactly a decade ago.

Last month we talked about one of Microsoft's big missteps with the Xbox One which was readily apparent at the time but has only become more obvious in retrospect, namely the attempted adoption of required daily online check-ins so that publishers could still command a fee when people bought a used game.

Microsoft's rush to force an inevitable and imminent future into the present was a spectacularly bad decision, a mistake that simply could not have been made at any other point in time.

Before the Xbox One, Microsoft couldn't be assured that its userbase could be assumed to have reliable online connections in order to facilitate the check-ins.

After the Xbox One, the shift to digital consumption had become so pronounced that there was basically no need for Microsoft to even bother rocking the boat with such a policy; consumers largely decided the convenience and deep discounts possible with digital distribution far outweighed the benefits of having a physical copy of the game to lend or trade in.

Today we're going to talk about another of Microsoft's terrible Xbox One strategies, but this one has a more timeless feel to it. It's the story of a company badly misreading the room, like Nintendo insisting people didn't want online games or Sony deciding it was fine to suggest users work longer hours to afford the PS3.

Xbox One was supposed to be the culmination of Microsoft's long-term strategy for the Xbox, the payoff for it getting into the console business in the first place.

The original Xbox lost a ton of money to establish a beachhead in the living room. The Xbox 360 made the brand a legitimate pillar of the industry, one every bit as relevant to gaming as Nintendo or Sony.

But Microsoft didn't want just another game system. It wanted its ecosystem to extend to every aspect of people's lives. How many people already interact with Windows every minute of their work life? The Xbox extended Microsoft's reach a little further into people's gaming lives, and the popularity of Xbox 360 apps like Netflix showed the potential for the company to have its hands on an even greater share of the 24 hours each user has in a day.

Those ambitions were absolutely the focus during the original Xbox One reveal, which kicked off with a monolog cobbled together from clips of developers, players, and celebrities like Steven Spielberg and J.J. Abrams each reciting a few words for an intro segment that was not shy about making Big Promises that were equal parts creepy, sad, and dystopian.

"We're about to change entertainment forever. Again. Because we're going to take all that we learned in more than 30 years of innovation, and use it to change everything. For the first time, you and your TV are going to have a relationship.

"It's going to recognize my name, my voice, my friends, my family, my movies, me. It's going to remember all the things I like, love, and really love.

"We're going to use ground-breaking technology and the power of the cloud to set my imagination free. Free to create worlds and feelings I can only begin to imagine, where I'll laugh more, cry more, scream more, and cheer more. Where I'll stop just watching and start feeling alive.

"Alive.

"Alive.

"Alive."

So there I was, all ready to have a consumer product reveal to fill the presumed sad void in my existence and have me start feeling alive. But just when I was about to experience self-actualization within the Xbox family of products, Microsoft instead served up one of the most deathly dull press briefings I've ever seen.

Microsoft interactive entertainment business president Don Mattrick came out to kick off the show and wave the first red flag, referencing Xbox's "new mission." That new mission included games, but it was definitely more interested in a bunch of things that were absolutely not games.

"Today, we're thrilled to unveil the ultimate all-in-one home entertainment system," Mattrick said, "the one with the power to create experiences that look and feel like nothing else. The one that makes your TV more intelligent. The one system for a new generation. Ladies and gentleman, introducing Xbox One."

After that, it was a flashy unveiling of the new Kinect sensor, controller, and the Xbox One itself, which met with the sort of uproarious approval you might expect from a well-orchestrated product reveal. But rather than capitalize on that momentum, they turned the show over to senior VP of marketing and strategy Yusuf Mehdi, who briefly said gaming stuff would be talked about later and at E3, "but for now, though, I want to share how we're going to take that passion for gaming and apply it to your entire TV experience."

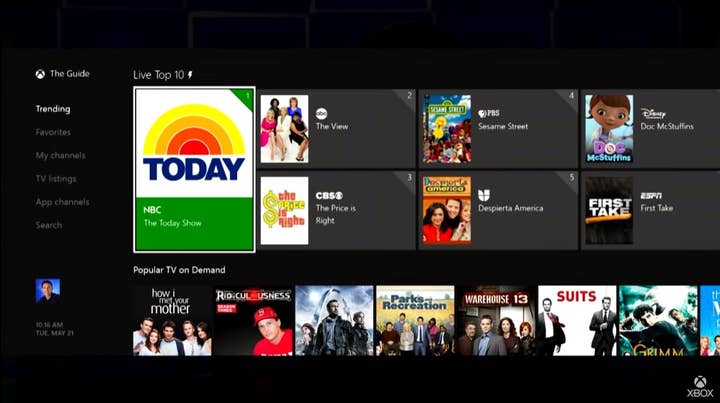

We watched some Price is Right. We watched a trailer for Star Trek Into Darkness and learned we could order movie tickets. We watched some basketball. We used voice commands to watch The Today Show. We watched people chat on Skype.

Fucking Skype.

Then we watched some more Price is Right. (Although in Microsoft's defence, Plinko is the literal manifestation of my passion for gaming applied to the TV experience.)

That took us to the 18-minute mark, with more than half of the show to that point consisting of Mehdi's TV demonstration. Next up was Xbox chief product officer Marc Whitten to talk system specs and Kinect talk, with some promises about the power of cloud computing that would never be paid off, unless you were a weirdly big fan of that one multiplayer mode for Crackdown 3 that finally arrived some six years later.

It was 33 minutes before we finally got our first focus on actual games, a pre-rendered hype trailer for the EA Sports lineup. And sure, sports games aren't necessarily what the core gamer audience shows up to console reveal events for, but they were undeniably games, and after such a long stretch without, the audience was probably grateful just to be edging into familiar territory.

The move toward what people actually cared about continued, as trailers for Forza Motorsport 5 and Quantum Break followed. But just when the audience might have suspected the show was getting back on course, it swerved right back into the world of Not Games with an extended Xbox Entertainment Studios segment focused on "our mission to transform television."

"Xbox is about to become the next water cooler"Nancy Tellem in May 2013

And here to detail those plans was Xbox Entertainment Studios president Nancy Tellem, who quickly established her credibility with the hip young gamer audience by, uh… namedropping her previous work at CBS on CSI and early '00s reality show phenom Survivor? Hrm.

"Only on Xbox will TV become social in ways unknown to us today, driven and shaped by the community of tens of millions on Xbox Live," Tellem said. "Xbox is about to become the next water cooler."

That's great, but you're not selling a water cooler, and telling people you don't really know what it will do is not a particularly compelling sales pitch. (Remember kids, if any exec ever hypes a potentially neat feature saying "We can't wait to see what people will do with this," it's probably because they don't have a clear and compelling idea of their own as to what people would want to do with it.)

Then 343 Industries' Bonnie Ross came out not to announce a new Halo game, but a Halo TV series "created in partnership" with Steven Spielberg. While Xbox Entertainment Studios was shut down the very next year in a Microsoft-wide restructuring, this was actually one of the more successful things to come out of the show. It just took a very long while, as the first episode of Halo's first season debuted almost nine years later in March of 2022.

Microsoft must have been worried about spoiling gamers with something even tangentially related to their interests, because the next segment was right back to the land of television with an extended discussion of Microsoft's partnership with the NFL.

I understand why Microsoft felt the need to include this segment, seeing as how the company was spending $400 million on this partnership (which also included Microsoft branding on sidelines and coaches using Surface tablets on the sidelines) and was more concerned with making the most of that money rather than making the most of the billions it had already spent to make itself a viable console player in the first place.

What I don't understand is why Microsoft felt the best way to talk about this partnership was a Don Mattrick one-on-one sit-down interview with NFL commissioner Roger Goodell. Whatever you might think of their business acumen or their moral culpability for the horrifying quality of life problems experienced by former players with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, neither is a particularly charismatic screen presence.

They proved unable to pull off the nigh-impossible feat of making me care about about Xbox One bringing fantasy football functionality to the console experience, much less that they were integrating it with Skype.

Fucking Skype!

We're at the 50-minute mark here, people. Microsoft blew way past "ill-advised" in this one and landed somewhere between Andreessen Horowitz's blockchain investment portfolio and Elon Musk paying $44 billion for an unprofitable social network knowing that it would thereafter be run by Elon Musk.

But Microsoft knew it couldn't end with the NFL and a release window announcement of "later this year," so its big finale was a look at the next entry in the biggest franchise in games, Call of Duty.

Activision Publishing head Eric Hirshberg took the stage with a bit of self-effacing humor showing he was well aware how the show had gone.

"Just to be clear, I am the last human speedbump standing between you and seeing the world premiere of the next-generation of Call of Duty up on that screen in a couple of minutes, so knowing my audience as I do, I'm going to try and get through this as fast as possible," Hirshberg said.

It was too little, too late. After an excruciating hour-long build-up, Microsoft's "one more thing" was a behind-the-scenes clip and trailer package for Call of Duty: Ghosts, a next-gen debut for the franchise that would disappoint both critically and commercially.

The most positive thing I can say about the Call of Duty: Ghosts capper – and perhaps the Xbox One reveal as a whole – is that it gave us the gift of "dogmouthing."

People hated it

Needless to say, this did not go over terribly well with a significant chunk of the audience. From the focus on TV and sports to the lack of any mention about the digital restrictions that had dominated talk leading up to the reveal, there was no shortage of complaints.

As far as us media types go, Rob Fahey called it confused and boring, saying, "The tone of Microsoft's event rankled gamers, for good reason – the reveal of a game console which focuses so heavily on how good it is at controlling television shows and movies shows basic disregard for the reasons most people watching the reveal online have to actually buy game consoles."

Our staff roundtable had a variety of views ranging from my "hated it" to Matt Martin's less judgmental description of the strategy.

"Xbox One isn't a video games console," Martin said. "Whether you like that or not, that's the case. Xbox One is the collective Microsoft entertainment and communications business sitting under your television. Games are part of that, sure, but Skype is just as important for Microsoft."

Fucking Skype?

We talked to a handful of indie developers, who definitely picked up on the differences between Microsoft's show and Sony's PS4 reveal, where prominent indie Jon Blow was given the stage for a lengthy segment promoting The Witness.

Double Fine's Tim Schafer told us he wasn't sure what to make of his future employer's new hardware because unlike Sony, Microsoft hadn't ever sought feedback about what kind of things a studio like Double Fine would want out of a new system.

"This will be a marketing game and right now Sony seems to be winning"DFC's David Cole

Analysts were split on the reveal, with DFC Intelligence's David Cole noting the different approaches Sony and Microsoft were taking, and expressing concern that Microsoft was "going after a need that isn't really there."

"In the US Microsoft has a major advantage but they could easily screw that up very quickly," Cole said. "We only need to look at Nintendo's disastrous recent product launches for a lesson. This will be a marketing game and right now Sony seems to be winning."

Wedbush's Michael Pachter likewise identified the approach as "exactly upside-down what Sony did," but thought that could be a good thing.

"Sony was all games all the time and this was all entertainment, saying games would be at E3," Pachter said. "The gaming press was really excited by the games focus by Sony, but I think this has more mass appeal and I think E3 is a games-focused show so I think maybe that strategy is smarter."

While much of the reaction to Microsoft's mass appeal push was negative, it was not terribly surprising to those familiar with the company.

Peter Molyneux saw his former employer's misstep coming well before the Xbox One was actually unveiled, saying, "The big question left in my mind and lots of people's minds, I think, is are they going to be saying this is the ultimate gaming console or this is something everyone should have in their living room? Because those two messages...trying to mix those two messages may just end up confusing people."

Even just-ousted Electronic Arts CEO John Riccitiello was foreshadowing Microsoft's problems in a guest column for Kotaku the day before the unveiling, saying, "The risk is that either or both of the new platforms emphasize these 'value-add' experiences too much, both in the user interface on the consoles themselves, or in the story they tell consumers when they unleash their avalanche of advertising."

Perhaps the most frustrating part of this is that outside of this crucial tone-setting reveal, Microsoft wasn't ignoring games. It was actually spending $1 billion to bring exclusive games to Xbox One, promising 15 such titles in the system's first year, eight of them new IPs. (Dead Rising 3, Titanfall, Ryse: Son of Rome, Sunset Overdrive, and Crimson Dragon were among the first-year console exclusives Microsoft did not mention at the event.)

If Xbox One really was intended to be Microsoft's Trojan Horse to take the living room, they probably would have been better served to make it look more like a horse and less like a troop transport with transparent walls.

What else happened in May of 2013

● While EA was busy conducting a search to find its next CEO, EA Sports executive VP Andrew Wilson sold every last share he owned in his employer.

The board must have seen that lack of faith in EA's future as evidence of a shrewd financial intellect at work; Wilson would be named EA CEO that September, and still holds the position today.

● EA was busy making deals, signing separate ten-year pacts to make FIFA and Star Wars games. Neither turned out quite as we expected, with the lengthy and lucrative FIFA-EA partnership dissolving last year as the publisher rebrands the series to EA FC and the Star Wars exclusivity going by the wayside with the likes of Zynga, Ubisoft, and Quantic Dream sharing the license in recent years.

● EA also broke some deals, saying it would stop making licensing agreements with firearms manufacturers, but would keep featuring their guns in games anyway.

I don't know, maybe if the gun makers aren't sending the legal team after you for blatantly unlicensed use of their products in your games, it means just having the guns in your games supports their business much more than whatever they made from licensing deals in the first place?

And not giving them the licensing money on top of that is a meaningless attempt to wash your hands of responsibility and criticism even as you continue effectively advertising their products to an audience they cannot directly market toward? Just a thought.

● Five months after release, Resident Evil 6 sales totaled 4.9 million copies, enough to make it the fourth best-selling game in Capcom's history, behind Street Fighter 2 on SNES, Resident Evil 2 on PlayStation, and the multiplatform Resident Evil 5. In one of those moments that ramped up hand-wringing about the sustainability of AAA development, Capcom called the sales disappointing.

● Blizzard gave up on Titan, its big MMO follow up to World of Warcraft that had been hinted at for years. While that project never came together, it led to the creation of Overwatch, which fared considerably better.

● With some free time on his hands after Disney closed Junction Point Studios, Warren Spector wrote a few guest columns for us, including this one that notes how Epic Mickey was his game with the lowest Metacritic average, but the most fan mail. It also included this lovely sentiment well worth taking to heart:

"At the end of the day, understand that 'success' is a word with as many meanings as there are people to define it. Choose your meaning carefully and live with the joy – and consequences – of your choice. In this way, life is like a game. If only more games were like life. Accomplishing that goal, making games more like life and encouraging others to do the same, is my definition of success – what's yours?"

Good Call, Bad Call

BAD CALL: Microsoft interactive entertainment business VP Phil Harrison said the packed-in Kinect sensor would be the Xbox One's game changer because every developer could count on every user having one.

In reality, developers didn't provide more robust support for Kinect because it didn't really suit the traditional games popular with early adopters and multiplatform third-party publishers still had most of their playerbase lacking Kinect because they were on PS4 (which sold better in part because it was $100 cheaper thanks to the lack of a pricey camera peripheral pack-in). Developers also couldn't count on everybody having one because it would start selling Kinect-less Xbox Ones less than a year after launch anyway.

BAD CALL: Just in case gamers weren't alienated enough by the Xbox One reveal, Don Mattrick drove the point home to the Wall Street Journal with an answer to Xbox One backwards compatibility questions that was equal parts dismissive and hostile, saying, "If you're backwards compatible, you're really backwards."

Microsoft would become really backwards two years later when Xbox 360 backward compatibility was one of its big E3 2015 announcements.

BAD CALL: Xbox senior director of product planning Albert Panello echoed Harrison's point about the benefits of a mandatory Kinect and also hyped up the promise of cloud computing to open up new kinds of experiences, but we're mostly including him here for treating an unpopular decision as if it were simply a matter of what was possible.

"To deliver the performance that we needed, we had to switch architectures, and that was just going to make backward compatibility impossible," Panello said.

Reminds me a lot of the excuses for SimCity and Diablo 3 being always-online because it was impossible to deliver devs' vision for the game otherwise, even though offline versions of SimCity and Diablo 3 were suddenly very possible once it suited the publisher's interests.

VERY BAD CALL: Those were all bad calls from Microsoft execs, but Yusuf Mehdi offered some sales projections that make those other calls look downright accurate. Mehdi was just the messenger conveying the company's internal projections, but there's nobody else here to shoot. Sorry Mehdi.

"Every generation, as you've probably heard, has grown approximately 30%," Medhi said. "So this generation is about 300 million units. Most industry experts think the next generation will get upwards of about 400 million units. That's if it's a game console, over the next decade. We think you can go broader than a game console, that's our aim, and you can go from 400 million to potentially upwards of a billion units."

The Wii U sold almost 13.6 million units, and Sony's final sales update for the PS4 last August put it at 117 million units.

We don't really know what the Xbox One sold. Microsoft stopped reporting hardware sales numbers in 2016 because they weren't as relevant as engagement metrics / looked real bad next to Sony's numbers.

Regardless, we're pretty sure Xbox One didn't sell the 169 million units needed to make that conservative estimate of 300 million for the generation, or the 269 million needed to hit the 400 million that "most experts" had predicted.

And somehow, even with Skype integration (say it with me now) it's still a safe bet the Xbox One still fell short of the 869 million units sold it would have needed to realize the generation's potential for 1 billion units.

GOOD CALL: It wasn't exclusively Bad Calls for Microsoft in May of 2013. After all, the company did say that it was finally getting rid of the value-obscuring Microsoft Points virtual currency for digital Xbox purchases and would instead allow people to purchase things directly for their exact asking price. It was way late in coming, but it was a Good Call nonetheless. Now if only the free-to-play market would follow suit...

GOOD CALL: In similarly belated but welcome news, Electronic Arts shelved its Online Pass program, an effort to undercut used game sales by locking online play behind a $10 paywall, but including a single-use code to unlock online play for free with every new copy of a game. EA had launched the Online Pass for its sports games exactly three years earlier, but was discontinuing it due to feedback as "many players didn't respond to the format."

BAD CALL: Nintendo began claiming monetization rights on YouTube videos featuring its games, because why wouldn't you try to take money from your biggest fans doing free marketing?

BAD CALL: In a post-earnings conference call, Activision Blizzard CEO Bobby Kotick pooh-poohed suggestions that the company was missing the boat on mobile, saying, "If you look at the last four or five years, you've seen changes in the top ten almost every year that are significant. Nothing that's driven any sizable amount of operating profit. While we're going to continue to look at it, and we think that over the long term there'll be opportunities, right now we just don't see anything that would suggest that changing the way we approach investing against mobile would be a good idea."

That same month, Candy Crush Saga claimed the top spot on the highest-grossing iOS charts. Activision Blizzard would change the way it approached investing against mobile two years later, when it forked over $5.9 billion to buy Candy Crush maker King, which is now the largest part of the Activision Blizzard empire despite not even sharing top billing in the company name.

You can debate whether Activision Blizzard was right to ignore mobile for so long (and I have done just that), but it's easy to imagine a different strategy would have let it establish itself in mobile quicker, cheaper, and with less reliance on external parties like NetEase (for Diablo Immortal) and TiMi Studios (on Call of Duty Mobile).