"It's just people selling picks and shovels, not the people finding gold"

FlowPlay's Derrick Morton on his "mobile last" strategy, and how specialist app stores could save the mobile market

The difficulty of finding success and stability on the app stores is a frequently discussed problem. Yet most small developers still use mobile as their target platform, whether through a lack or proper understanding or a perceived lack of options. According to FlowPlay's Derrick Morton, however, there is another way, one that puts mobile where the economics suggest it should go: not first, but last.

Speaking at the Casual Connect conference in San Francisco last week, Morton, the CEO of FlowPlay and an industry veteran of some 20 years, delivered a decisive and damning assessment of the mobile market.

"The system is really, really broken," he said, citing its inability to sustain a model of developers, publisher and distributors as the most obvious evidence of that fact. "That [model] has been going on ever since I've been in games. But the publisher model does not work in mobile. Because of the razor thin margins there's not enough pie to split."

Anecdotal and statistical evidence that the mobile market yields workable revenues for just a tiny proportion of developers is not difficult to find. Morton offered an example of his own: if you're not in the top 200, your company will have to run on less than $2 million in revenue a year. While unsourced, that figure is certainly consistent with other available data, as was Morton's following point that, "the vast majority of games make no money at all."

"The publisher model does not work in mobile. Because of the razor thin margins there's not enough pie to split"

Morton further bolstered his position with the absolute dominance of a small handful of companies - namely Supercell, Rovio and King, which took 50.2 per cent of all mobile revenue in the US in 2014 - and the troubling trend that total revenue growth is slowing down. According to data from eMarketer, total mobile revenue increased by 70 per cent heading into 2013, but it's expected to grow by just 9 per cent by next year. Then there's the incessant flow of new product, with around 450 new games submitted to iTunes every day - 14,842 games in May 2015 alone, according to Morton's data, with almost 400,000 "active" games already available.

"How can you possibly be discovered with all that noise?" he asked the crowd, before supplying the equally problematic answer: you spend money.

"You can walk around the show-floor here [at Casual Connect] and see how many companies are in the business of customer acquisition, versus the business of making games," he said. "The acquisition people far, far outnumber the people actually making the products. That's a little scary. It's just people selling picks and shovels, not the people finding gold."

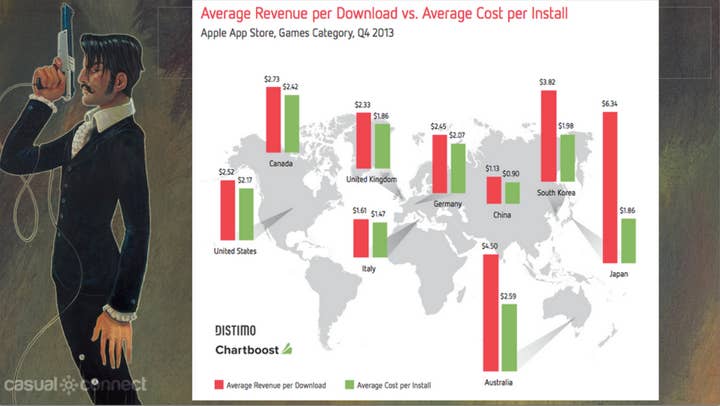

Which goes back to those "razor thin margins" that Morton mentioned at the start of his talk. In Europe and North America, where a high proportion of smaller developers focus their efforts, the cost per install for a mobile game is only a few per cent lower than the revenue they will receive from that download. In the US for example, the margin is down to just 35 cents.

And that's a relatively recent shift, one that, if you started working on a project this time last year, would likely undermine your marketing plans and cost structure. Morton referred to Fiksu's Cost per Loyal User Index, which measures users who download a game and launch it three times: In May 2015 the cost to acquire such a user was $2.47, and that's 50 per cent higher than in May 2014. The conditions of doing business have changed radically even in the last 18 months.

The promise of mobile, Morton said, was a platform with low barriers to entry, which could therefore sustain a larger number of small and independent developers than other markets. But the barriers are now dauntingly high, the proportion of winners to losers almost absurdly skewed. All available evidence suggests that a sensible strategy is no longer mobile first, but "mobile last."

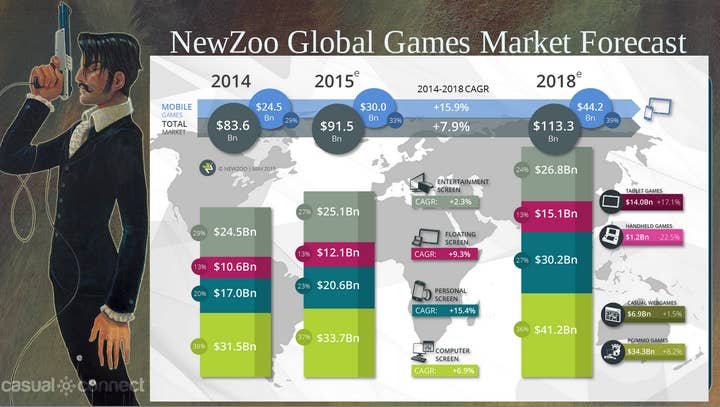

Morton used data from Statista to make the case that, while shipments of laptop and desktop computers did decline between 2011 and 2014, they are expected to level off over the next several years, as far ahead as 2019. Newzoo also estimates that revenue from games on these computers will have a compound annual growth rate of almost 7 per cent leading up to 2018.

That's lower than the corresponding figure for mobile and tablet games, but still attractive given the more favourable market dynamics. In social casino, Morton said, revenue generated from computers (generally from web games) is higher than mobile revenue, and the costs tied to that revenue are also lower. Morton offered Wild Tangent, Kongregate and Yahoo Games - along with more obvious choices like Facebook and Steam - as examples of places where developers can make a more practical start, and build towards a mobile launch, if they choose to launch on mobile at all.

"Places still exist where you can take a web game and make money from it," he said. "You can take a product that you're considering taking to mobile and test it out first, see how consumers respond, see what your return rates are, what your ARPU is. You can learn that before you go to mobile and start spending real money... If you really just want to test and see what happens before you move to mobile, you really only need a couple of thousand customers. That will tell you a lot about your game, and it leads to better day one reviews."

This is the best possible approach to mobile for smaller teams, Morton said, though it won't do anything to change the fundamental problems with that market. Indeed, Morton expressed his apparently sincere regrets that mobile had wound up in this position, thanks in no small part to the way Apple and Google inserted themselves into what should have been a more democratic process.

"The App Store and Google Play, the established intermediaries between you and your games, give you one point of contact. It shouldn't have happened that way," he said. "Do you buy all your software from Dell when you buy a Dell computer? No, you don't. Do you buy all your software from Microsoft when you have the Windows OS? No, you don't. But when you have an Android device or an iOS device, you're pretty limited on where you can get software for that device.

"We need specialists, who really love and breathe and live their games. Not the one-size-fits-all stores we have now"

"It didn't have to be that way. There's no reason why this couldn't be a different system, where everything happens in a browser and we can freely promote our products through search tools and the web. But the two powers that be decided they would be the intermediaries and control everything. That makes it really hard."

One way of shifting the balance would be through the rise of smaller, independent storefronts, Morton said, and there are certainly people attempting to make that happen.

"What makes more sense is store-fronts that specialise in the kind of game that you play. If you're a mid-core player, why are you getting your game in the same place as Candy Crush? That doesn't make sense. We need specialists, who really love and breathe and live their games, who do a great job of editorialising and presenting those games. Not the generic, one-size-fits-all stores we have now."

This final point had an unexpectedly personal resonance. In my early teens, when I was just starting to recognise the specific kinds of entertainment I enjoyed, there was an independent game retailer opposite my local supermarket. Every item in that shop - from its narrow selection of the latest releases to Japanese imports to curios for the Spectrum and Commodore 64 - was hand-selected by the owner. If you were of a certain disposition, you could choose blindly and still strike gold.

It was there that I really discovered my sense of self as a gamer, and I believed that sort of intimate consumer experience had been lost amidst the noise of the digital age. Morton is right: we need that intimacy now, perhaps more than ever before.