Is VR fulfilling its promise this time around?

On the fifth anniversary of the Rift Kickstarter campaign, early backers assess how it's gone and where it's going

Tomorrow marks the fifth anniversary of Oculus launching its Kickstarter campaign for the Rift, kickstarting not just a VR headset but a new era of enthusiasm around the technology in the process. The company promised a device that would "change gaming forever," and made its pitch with the endorsements of some big names in the industry, including id Software's John Carmack and Valve's Michael Abrash (both now with Oculus), Epic Games' Cliff Bleszinski (now with Boss Key), Unity CEO David Helgason (now merely a board member), and Valve's Gabe Newell (still with Valve).

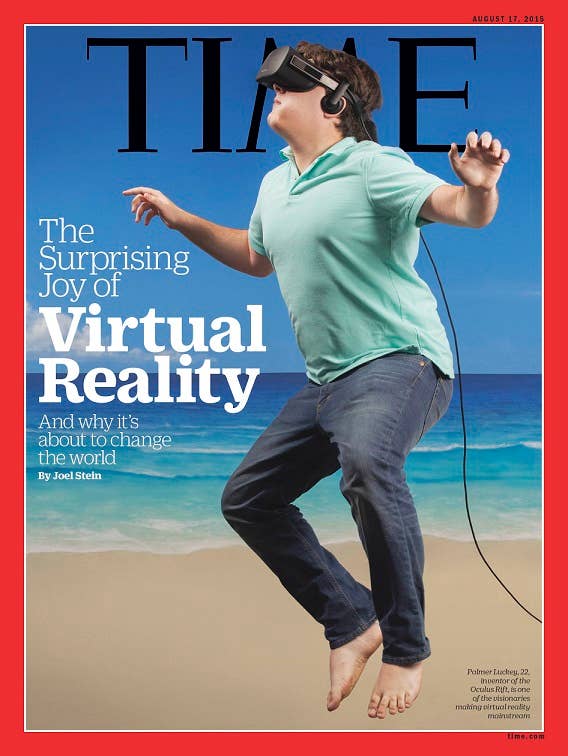

Featured alongside those leading lights was then-unknown Palmer Luckey, Oculus founder and Rift designer, explaining how the whole project began in his parent's garage in Long Beach, California.

"There was nothing that gave me the experience that I wanted: The Matrix, where I can plug in and actually be in the game," Luckey said. "And I was sure that somewhere out there, there was something I could buy. And the reality is there's nothing. I set out to change that with the Oculus Rift."

In the weeks leading up to the anniversary, GamesIndustry.biz reached out to a number of the Rift's original Kickstarter backers to see what they thought about where Oculus is now, what it's done along the way, and if the new era of VR is panning out as they hoped it would five years ago.

The backers we spoke to had largely similar reasons for backing: They were excited by the same promise of VR that Luckey was trying to realize. Daily Kos writer Mark Sumner was a VR fan from the last wave of the tech; he still owns a pair of Virtual I/O i-glasses and admitted to spending an "ungodly" amount of money to witness low-poly pterodactyls at a Virtuality mall kiosk.

Sidewords and FutureGrind developer Matt Rix was sold on the Rift by the pitch video's parade of industry luminaries, saying, "By the time it reached Gabe Newell's endorsement halfway through the video, I paused the video and immediately backed the project."

Voxel Quest developer Gavan Woolery had already been tinkering with his own VR devices, and saw tremendous potential in Oculus' approach. Gunmetal Arcadia developer J. Kyle Pittman thought Oculus' approach to the tech was both smart and practical. And finally, Battlecruiser 3000AD developer Derek Smart wanted to be in on the ground floor of what he thought would be "The Next Big Thing."

"I don't think Facebook was the best match, since they are a company based around making money from advertising, but there could have much been worse buyers."

Matt Rix

While the $2 billion acquisition by Facebook in March of 2014 was not universally welcomed at the time, our limited sample of backers had relatively few misgivings about it.

"I felt like some kind of acquisition was inevitable," Rix said. "They needed that kind of money to really make things take off. I don't think Facebook was the best match, since they are a company based around making money from advertising, but there could have much been worse buyers."

Rix might not have been surprised, but some of his fellow backers definitely were.

"I was shocked by the price tag Facebook paid," Sumner said. "Having played with earlier VR gear, it wasn't clear to me that Oculus was bringing anything to the game that didn't come free with better screens and faster processors. I had a hard time seeing the IP that was worth the purchase."

Ultimately, Sumner didn't seem bothered by it, particularly because the company announced after the acquisition that everyone who received a dev kit through the Kickstarter would get a commercial version of the hardware for free. Woolery and Smart had similar reactions.

"The Facebook acquisition was pretty shocking," Smart said, "especially when I read the amount of money involved. But the deal didn't change how I felt at all. That's why I didn't quite understand what the furor was about. It's not as if the backers didn't get what they backed. All backers received what they were promised, and that's where the promises ended."

Smart and Sumner differed more widely when it came to Palmer Luckey and the funding of a pro-Trump "shitposting" group that led to his departure from Oculus.

"Due to the outrage culture that's being cultivated in our industry, all I can say is that, for the most part, it was immaterial and irrelevant," Smart said. "Visionaries come and go, some are good, some are not so good. Nobody is infallible. As a result, people have to understand that Oculus was a team effort, and wasn't down to any one person."

Sumner, on the other hand, was "genuinely pissed off" by Palmer's actions.

"It wasn't that he got political," Sumner said. "I'm political. It's that he chose to express his political views in a way that was explicitly dickish. Purposefully vile. It made me think that if you take a kid who has already been lavishly praised for what amounts to a few months work, then hand him a metric fuckton of cash, he may never realize that the 'heroes' of Atlas Shrugged are all horrible, immature assholes."

However, Sumner apparently agreed with Smart when it came to not holding the rest of Oculus accountable for Luckey's actions. At the time Luckey's political activities came to light, Sumner had been working on a Rift project that would use god game mechanics as a way to help corporate sites visualize operations and productivity. And while he publicly mused that he was considering dropping Rift support, Sumner said he quickly resumed development for the Rift regardless.

"[B]y the time the dust settles in the coming months and years, we could very well be looking at another AdLib vs. SoundBlaster showdown all over again. And at this time, I have no reason to believe that Oculus will survive that rift..."

Derek Smart

Rix and Pittman both called the situation "disappointing," while Woolery said Luckey did nothing wrong and was unfairly targeted for his political views. None suggested that Luckey's actions should have been held against Oculus as a whole.

So are they still happy to have backed the Rift? The answer was basically yes for everyone we spoke to, though there was a wide range of attached caveats. Woolery was disappointed with the original Rift dev kit he received because it lacked 6-axis tracking, but felt he got more than his money's worth when the retail version was delivered to him for free. Pittman said he's glad he was an early supporter, even if he's never gotten much use out of the headsets he received--his PC isn't even powerful enough to run the retail model--and hasn't kept very close tabs on the field.

"I'm still glad I backed it," Rix said. "I think it helped to accelerate this medium of VR/AR that is only beginning to take shape. With that said, I don't think Oculus is leading the way any more. Valve has much better tracking tech, and VR is all about tracking. I think Oculus has tried way too hard to become the Apple of VR, with a closed ecosystem, and that has really hurt them. I also think their choice of tracking system was an incredibly poor decision that will hurt them more and more as time goes on."

Smart stressed how proud he was to say he was there at the start, but was less glowing about the Rift's performance since.

"I have all three leading VR devices," Smart said. "While they all have their strength and weaknesses, I feel that Oculus made some damaging and detrimental mistakes on their road to the retail market. Unfortunately, the other vendors learned from those mistakes, and didn't have much catching up to do. It is still a great device; but unfortunately, in my opinion, by the time the dust settles in the coming months and years, we could very well be looking at another AdLib vs. SoundBlaster showdown all over again. And at this time, I have no reason to believe that Oculus will survive that rift, regardless of how much money Oculus throws at it. At least not as far as gaming is concerned."

Meanwhile, the Rift is Sumner's VR headset of choice.

"I won't scream that I love my Rift," Sumner said. "The view is still too restrictive. The 'god rays' still too intrusive. And my screen acquired a series of crimson blotches just from sitting it down on the desk for a couple of hours and allowing the sun to touch it's too-delicate innards. However, I've played with all the outfits on the market at the moment and I still enjoy the Rift the most. We're at the point where we're just starting to get some genuine applications that were not just 'designed to work in VR' but designed to work only in VR. Star Trek Bridge Crew would be my prime example. It may be the first application that not only dragged me into playing VR for hours, but made me click a button to socialize with strangers -- something that decades of social media hadn't managed. Rift isn't a practical product. Yet. But it's a nice preview."

Then again, Sumner isn't the type of VR devotee for whom practicality is a big concern.

"I honestly have a room of my house set up with alternating squares of light and dark padded flooring, a shelf around the walls to hold sensors, and an overhead cable handler stolen from a TV projector setup to keep me from tripping over cables," he said. "I'm pretty dedicated to the idea that VR is not a passing fad. That said, I think we're still one generation of graphics card away from being able to push the number of pixels necessary to give the average consumer a convincing 'oh ah' experience that extends beyond a brief demo and makes VR rigs as ubiquitous as a mouse."

"Maybe the games industry as a whole jumped the gun on throwing a lot of money and attention behind VR..."

J. Kyle Pittman

His fellow backers all had their own assessments about just how far VR had come in the last five years.

"It is about where I expected," Woolery said. "At this point I think we are more limited by GPU cost and horsepower than anything else, although one major thing lacking in current VR hardware is accurate eye tracking, and thus 'true' depth-of-field."

Rix was similarly at ease with VR's recent progress, saying, "I never thought this kind of 'high end' VR would get super popular right away. The PC hardware to run it is just too expensive, and besides that, the experiences just aren't there yet. There are lots of interesting games, but not a lot of games that you would want to play every day. Once the novelty wears off, the friction of VR takes over. There are very few games that I've played more than one session of. When it comes to the tech itself, I'm happy with how it has progressed, especially on Valve's side. I think Lighthouse tracking was a massive step forward."

Pittman thought the resurgent wave of VR hype may have set expectations a bit too high, too early.

"Maybe the games industry as a whole jumped the gun on throwing a lot of money and attention behind VR because it still feels like consumer-grade equipment doesn't really exist at an affordable price yet, and I don't know there's an audience for any of this stuff until that happens," he said. "As a developer, I would not feel comfortable developing anything for virtual reality unless I were paid loads of money to do that. Who's my audience? I don't know anyone personally who has any of the consumer hardware besides the one I got for being a backer. It feels like we're still maybe 5 or 10 years away from being able to have that experience, but I'm glad the headsets exist and developers are making those games."

Smart was somewhat more dire, saying, "All things considered, it hasn't caught on as fast as I think the creators hoped that it would. I have always viewed VR gear, at least for games, as I have joysticks. Back in the day when flight simulations were all the rage, and we had a lot to choose from, they were a necessity. As advancements in game design, technology and input devices improved, the joystick ended up being a niche novelty item for the most part. And in turn, so did the simulation games that used them. Publishers abandoned the genre, and joysticks headed south. When the next-gen consoles with less bulky gamepads showed up, and slowly became the de facto standard for input gaming, it solidified the joystick's place in gaming as a niche novelty item. That's what I see in the future for VR gear and games."

Smart wasn't alone in his skepticism. Perhaps surprisingly, none of the backers we spoke to could really be accused of looking at VR's future through rose-colored headsets.

"I am rather pessimistic about VR in the short term," Woolery said. "And I think in the long term VR probably won't be necessary, at least how we imagine it now. Relatively non-intrusive surgery will probably allow us to manipulate the optical signals directly, and perhaps even the vestibular system as well. It sounds like creepy sci-fi material, but I am far from the first person to propose it."

"To be successful, VR is going to have to accumulate not 10,000 clever tech demos, but more solid experiences. Of which there is currently maybe one..."

Mark Sumner

Rix also saw VR as a stepping stone to something else, saying, "I think the future of mainstream VR is the convergence of AR and VR in mobile devices with inside-out tracking and optical displays that can 'black out' the outside world. I don't know how long this will take to get right, but it won't be a sudden thing with a single magical device. It'll be a gradual process where devices get better and better until they become commonplace."

Pittman said cost is still the biggest obstacle in VR's way, but by no means the only one.

"To really develop an audience, I think you need hardware that's both cheap and high quality," he said. "If it's too expensive, nobody's going to take that plunge. If it's cheap but also low quality, people will try it and it won't be what they thought it would be. It needs to be affordable and high quality, and obviously that's a difficult thing to deliver on unless the hardware makers just eat that cost to build an audience. Beyond that, there needs to be some killer app. I haven't seen that myself yet and I don't know what that would be. I don't know if that will even be in games. It could be the Facebook social media experience; it could be something in any other field."

Sumner had a laundry list of things that need to happen for VR to fulfill its potential. It needs to be cheaper, better, lighter, more comfortable, wireless, with broader support from developers and and some killer apps to convince people the price tag is worth it.

"To be successful, VR is going to have to accumulate not 10,000 clever tech demos, but more solid experiences. Of which there is currently maybe one, if you add Elite and Star Trek Bridge Crew together."

Though he's clearly an ardent supporter of VR, Sumner gave voice to a nearly existential threat facing the medium here five years into its resurgence, and one pointed to far less frequently than issues of cost and comfort and support.

"We're halfway home," he said. "It shows promise, but it's not clear that we'll make it over the hurdles this time or the big dogs will give up before that point and VR will spend another decade or two in the hobbyist wilderness."