Is crowdsourcing less ethical than free-to-play?

Ben Cousins looks at the "ethical scorecard" for a variety of business models; F2P is under fire from the establishment, he says

Free-to-play (F2P) for many is still a dirty word. The biggest complaint often voiced is that F2P simply isn't ethical, that it's loaded with bait-and-switch ploys, and that it's targeting children as "whales" more than any other group. If you ask Ben Cousins, GM of Scattered Entertainment, none of this is actually true. In a GDC talk titled "Is Your Business Model Evil? The Moral Maze of the New Games Business" he looked at an analytical model for determining how ethical a business model is or isn't. His "ethical scorecard" yielded surprising results.

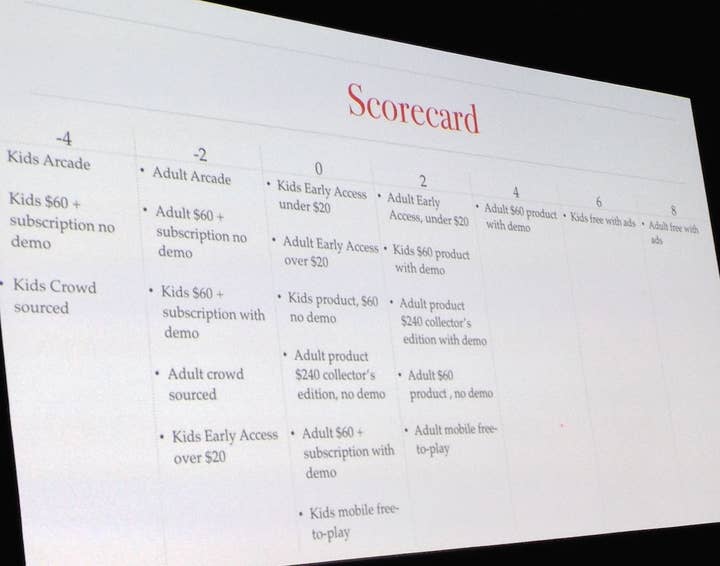

The key ethical issues listed on the scorecard include:

- Are purchase decision aimed at under-18s?

- Is it easy for an under-18 to spend without parental approval?

- Can the consumer play the game before spending?

- Are independent reviews available before spending?

- Are there time-limited offers? Random chance? Emotional appeals?

- Is the minimum purchase size under $20?

- Can the consumer spend more than $240 on one game?

- Can customers get refunds easily?

By assigning a +1/-1 point value to a yes/no response on each of these questions, a simple score can be determined. The higher the number the better in terms of a model's ethical nature. In the end, Cousins' scorecard looked like this:

As you can see, F2P games (whether for kids or adults) scored towards the middle to even positive territory whereas crowdsourced games, subscription and arcade were found to be less ethical overall. Interestingly, while crowdsourcing is vastly different from F2P, there are some parallels. Around 50 percent of total revenues on most crowdsourced games comes from just 10 percent of users; that means that crowdsourcing actually follows a similar "minnows and whales" pattern as F2P and yet Cousins noted, "I've never seen people accusing Kickstarter as manipulative or coercive."

Why is that? Cousins believes it's a result of how the "establishment" in the games industry perceives games and business models. The models that are treated as benign ended up scoring badly, and yet F2P, which scored fairly well by comparison is often under fire. Cousins said that developers are "dealing with the shock of the new" when it comes to business models like F2P. They fear the worst, but over time as more research comes out and as they see that bad things aren't really happening, that fear dissipates. Even the telephone, as a new technology, was considered to be dangerous at first. In fact, pinball machines were made illegal in New York City up until 1976 because Mayor LaGuardia alleged that these pinball games were robbing school children of money.

Cousins also said that F2P is suffering from the "outsider effect," meaning that F2P developers are often outsiders compared to the establishment, and if you don't know the people it's easy to assume the worst. Another factor is that the establishment wants to protect their definition of a "real game." Cousins said that this is often defined as "how I experienced games in my childhood" or in a "golden age." The establishment doesn't believe that F2P games respect the history of gaming.

The truth, however, is that F2P is the world's biggest business model by participation and soon it will be by sales as well, Cousins believes. This rapid growth can be threatening to the establishment who are worried that their power will be diminished by this growth. Another argument is that games are art and that art shouldn't be directly mixed with business or marketing. F2P games essentially marry commerce and design in a very upfront manner and some in the establishment consider that to be sacrilegious. For other models, the aggressive marketing takes place outside the game, not in it. But it's for that reason that Cousins thinks that game reviewers need to pay special attention to monetization in F2P games. He said that reviewers should specifically be looking to review monetization, and not just the game itself.

Ultimately, the stakes for F2P are massive now, and competition is extremely fierce as a result. Cousins said he's seen some F2P competitors attacking each other in order to gain an advantage. "I think that's unnecessarily bringing up issues that don't exist," he said. If anything, it's time to "stop infighting, and come together as an industry." Cousins believes that as F2P continues to grow (he thinks F2P revenues will surpass traditional by 2017) and the overall industry expands, there will be more and more scrutiny from the outside, and the industry will need to work together to defend itself.