How to patch out implicit bias from your hiring process

Speaking at Ludicious X, Celia Hodent suggests avoiding discrimination when recruiting is much like improving a video game

The industry has often stated its desire for a more diverse workforce, but progress in accomplishing this is painfully slow.

During her talk at Ludicious X 2020, game user experience consultant and psychologist Celia Hodent discussed how implicit biases are holding the games industry -- and all industries -- back.

Unconscious bias are ones we may not even be aware we have - you can read more about it in our GamesIndustry.biz Academy guide on the topic.

Fortunately, there's a game development approach recruiters can take to fixing this.

"The lack of inclusion in the games industry is an issue that can be tackled with a UX mindset," she told attendees. "It's all about understanding how the environment is going to favour human flaws."

Hodent clarified that by environment, she referred to the hiring process or career development for existing employees.

She demonstrated the consequences of implicit bias with a video of an automatic soap dispenser that did not recognise non-white hands, which Hodent suggested showed it was only developed and tested by white people.

"This is the reason why you need a diverse team, so that the product or the video game you're making is going to offer the best experience to everyone," she said.

"The problem is that we have a lot of cognitive biases. Our brains are pretty flawed. That's why we need to understand the biases that are implicit so we can fix the system accordingly."

The problem with our brains

Hodent offered another, more famous example -- The Linda Problem -- which explains how our brains process information.

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations. Which is more probable?

- Linda is a bank teller.

- Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Most people will say it's option two, falling for the conjunction fallacy. It is, in fact, option one: a person is more likely to be one thing than they are to be two things, but the brain is biased by all the additional information it is given.

Hodent cited the book 'Thinking, Fast and Slow' by Daniel Kahneman, which posits the brain has two systems for thinking. The first is fast, automatic and effortless, and is used most of the time as the brain is constantly making decisions. The second is slow, controlled and effortful, and is employed when we're tackling a complex calculation or trying to think outside the box.

The first system is inherently very biased, it's the system that "makes us fall into traps."

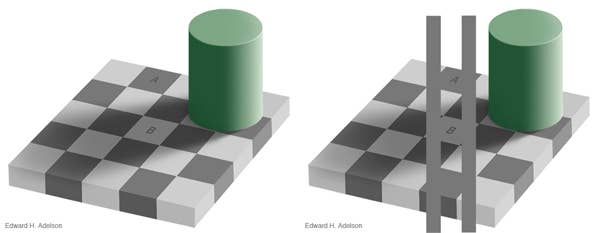

"You need to think about these kind of biases very much like perceptive illusions," said Hodent, offering a pictorial example.

In the image on the left, squares A and B are the same colour, as the image on the right shows. Even when informed this is a visual illusion, the brain still processes the image quickly and makes the intended mistake. Hiring can be the same, Hodent warned.

"Even when we know there's a bias, we fall for it," she said. "Cognitive biases are like that, they're implicit. Even though we know they exist, we still fall for them."

She offered two prominent examples of implicit biases.

In-group bias

The In-group bias is the tendency to give preferential treatment to others that you perceive to belong in the same 'group' as you -- a prime example of a bias that can perpetuate discrimination.

"For example, I'm a woman, I'm white and I love video games," Hodent offered. "I'm going to give preferential treatment to the people that I perceive belong to my group.

"Of course I'm not going to do it on purpose, but it's still going to happen. We connect more easily to people who look like us."

The halo effect

Similarly, the halo effect is the perceived spilling over of someone's positive or negative traits from one personality area to another.

"If you admire one of your colleagues because they did an amazing job on a game, it's going to be hard for you to believe they did a bad thing," said Hodent.

"These biases are influencing us to make bad decisions and they're polluting our critical thinking."

The impact of biases on hiring

Hodent cited a study by the Harvard Business Review to show the consequences of implicit bias when hiring. Most notably, the study found that people with the same skills or behaviour are still judged differently depending on their race, ethnicity or gender.

For example, applications from Black and Hispanic men were "often seen as lacking polish [in certain skills] and moved to the reject pile" even when they were stronger in other areas. Meanwhile, white men who lacked polish were deemed coachable and left in the running for the position.

A similar pattern emerged among men who appeared shy, nervous or understated. Non-whites were rejected for being unassertive, but in white people modesty was seen as a virtue.

Among candidates who were lacking in maths, women were rejected for not having the right skills while men were given a pass because interviewers "assumed they were having an off day."

"Again, we don't realise this is what we're doing at the time," Hodent said. "This is why we need to change the way we hire people so that we don't fall for these biases."

Can AI save us from bias?

The short answer is no: even artificial intelligence will share our biases.

"[Fixing biases] is like user experiences for a video game. We don't ask players to change their behaviour, we iterate"

Hodent demonstrated using an older version of Google Translate. The Turkish language has no gender, unlike English, so use Google Translate converted the phrase "He is a doctor" or "She is a doctor" into the same Turkish phrase: "O bir doktor."

However, if you took that phrase and translated it into English, Google produced "He is a doctor." Enter "O bir hemşire" and it produced "She is a nurse." Google Translate assumed doctor is a male role, and nurse is a female one.

It should be noted that Google Translate has been updated at some point to overcome this, now offering masculine and feminine alternatives when translating to English. But it still demonstrates the AI had to be manually altered to overcome the bias.

Changing the environment

Hodent posited that the solution is understanding how the environment -- i.e. the hiring process -- is shaping people's behaviour.

"This is pretty much like doing user experiences for a video game," she said. "When players don't have the experience we hope for, we don't ask them to change their behaviour, we change the environment instead, we change the game and iterate on it.

"This is what we need to do with the workplace environment to understand what it is at the workplace that is making people fall for their biases and not be inclusive. So let's change the system."

To do so, the industry needs to come up with "nudges" -- elements designed to influence how people interact with the environment. A simple example is putting plate on one side of a door rather than a bar, 'nudging' people to push instead of pull to open.

Hodent offered the example of a cleaning manager at Amsterdam airport who wanted to reduce spillages around the urinals. Instead of putting more warning messages on the walls, he added stickers of flies right next to the drain of the urinals to give people something to aim at. It resulted in an 80% decrease in spillages.

"If you're working on improving inclusion in the hiring process at your company, you need to design the process in such a way that reduces race and gender biases," she said.

Blind interviews: A possible solution

Hodent offered the example of blind interviews as something that could be adapted to games industry hiring processes, or at least inspire the sort of nudges we need.

In the US during the '70s, it was noticed that orchestras rarely included female musicians. Was this because women weren't as talented? Or because there was a bias during the recruitment process, because most people on the juries were white men?

One experiment showed it to be the latter: they added a curtain during auditions in order to hire people based on their talents, not on how they look. This led to a 30% to 55% rise in the number of women on orchestras.

"They had to iterate, because to begin with there was no carpet so they could hear women's heels on the floor," Hodent said.

Why it's important to subvert these biases

"Some people say that they're colour-blind and they don't evaluate people on how they look, just entirely on their skills," Hodent continued. "We have to be very wary of that because most of the time, well, it's bullshit.

"And even if we think we are inclusive, we are going to be influenced by our biases. There's no way we can escape that. Even if you try hard to not be influenced by how people look or sound, it's implicit. We need to really realise that so we can understand our biases better and change the environment to avoid them."

She added that designing for inclusion is not only the right thing to do humanely, it's also good business. Developers will be able to reach broader audiences, but doing so requires a diverse team.

"To design for inclusion, you need diversity and inclusion on your teams to counter blind spots in expertise," she said. "To have diversity on your team, you have to combat implicit biases within your hiring and promotion processes.

"We cannot control these biases, please remember that. What you can control is the environment. You can change the hiring process, for example. Use nudges."

Hodent offered another quote from Kahneman, who said: "People who are cognitively busy are more likely to make selfish choices, use sexist language and make superficial judgements in social situations."

"We know how cognitively busy we are in the games industry," Hodent said. "This is why it would be a fallacy to train people against biases. What's important is to know about these biases so we can change the environment instead.

"We mostly talk about discrimination against women and people of colour, but there are many other discriminations, like against older people, disabled people, LGBTQ+ communities and so on. We have a lot of work to do.

"We need to understand how the brain works, to understand its flaws and our biases, so we can design better environments for our games, at the workplace and in society. If we really care about stopping discrimination and making the world a better place for everyone, we really need to understand how we contribute to that injustice -- most of the time, implicitly. "