GameStop trades in its future for insultingly low amount

10 Years Ago This Month: Used games retailer endorses EA's Project $10 anti-used game initiative, sees little in return

The games industry moves pretty fast, and there's a tendency for all involved to look constantly to what's next without so much worrying about what came before. That said, even an industry so entrenched in the now can learn from its past. So to refresh our collective memory and perhaps offer some perspective on our field's history, GamesIndustry.biz runs this monthly feature highlighting happenings in gaming from exactly a decade ago.

GameStop gets pre-played by Project $10

May is financial report season in the games industry, with many of the largest companies reporting results for the fiscal years that wrapped up at the end of March. Ten years ago, most of those numbers were not very flattering.

There were a couple of outliers. Square Enix was booming after its acquisition of Eidos and a strong slate including Final Fantasy XIII, Batman: Arkham Asylum, and Dragon Quest IX. Activision Blizzard likewise posted strong results for its first quarter of the new year, driven by the usual suspects like Call of Duty and World of Warcraft.

But just about everyone else was struggling. Nintendo saw its stalwart DS business running out of steam while the Wii software lineup withered. Sony finally started to move some PS3s, but posted a staggering $889 million loss for its gaming division. Microsoft reported its quarterly results in April, showing a modest dip in hardware and software sales.

Electronic Arts, Capcom, Sega, and Ubisoft all reported significant sales declines as well. The general malaise of publishers jived with the NPD Group's monthly sales figures, which showed physical US game industry sales were down 11% for the first four months of the year, and headed in the wrong direction after April sales were down 26%.

"April 2010's results will only exacerbate the growing concerns about the long-term viability of the traditional retail packaged goods market..."

Analyst Jesse Divnich

There were a number of commonly cited reasons for this. The market hadn't yet recovered from the global economic crisis. The console cycle was almost five years old at this point. In a story we ran compiling a number of analysts' assessments, Wedbush analyst Michael Pachter suggested investors were "spooked" about the prospects of games publishers.

In a note to investors, EEDAR analyst Jesse Divnich said, "April 2010's results will only exacerbate the growing concerns about the long-term viability of the traditional retail packaged goods market as back catalog sales and mainstream/casual titles continue to deteriorate at a quicker pace over expectations."

Cowan and Company's Doug Creutz looked at the April numbers -- specifically the rapid deterioration in sales for games like God of War 3, Final Fantasy 13, and Battlefield: Bad Company 2 after launch -- and hypothesized that games without robust online or multiplayer functionality were losing sales momentum almost instantly because the people who bought them at launch traded them in, and customers in subsequent months just bought the cheaper used copies instead of new ones.

That perception probably wasn't hurt by GameStop reporting record first quarter sales while the NPD's numbers -- which don't include sales of used games or hardware -- were down sharply.

Publishers had rankled about GameStop's pre-owned business for years. They hated having a major retail partner competing with them, buying back the latest AAA games for a relative pittance and then pushing customers toward those used copies instead of buying a new copy that actually put money in the publisher's pocket. While in previous generations they didn't have much recourse, the dawn of connected consoles gave them some options to discourage buying used.

Electronic Arts was one of the first to roll out their anti-second-hand schemes with Project $10, an effort to give every new game a DLC add-on for $10, and then include a free one-time use code for that DLC in new copies. That way, people who bought a second-hand copy would have to pay the extra $10 for the full experience, possibly wiping out whatever savings they would have seen from buying used in the first place.

Other publishers were quick to jump on the bandwagon. Ubisoft made no secret that it was planning to mimic Project $10 with its own games. Meanwhile THQ gave its own characteristically cut-rate version of the idea a go, charging $5 for second-hand purchasers to unlock online features in UFC Undisputed 2010.

Perhaps surprisingly, GameStop was actually on board with this idea, at least in public.

"We do not anticipate an impact to our used margins due to this program"

GameStop COO J. Paul Raines

In the EA press release announcing the Online Pass promotion, GameStop CEO Dan DeMatteo is quoted as saying, "GameStop is excited to partner with such a forward-thinking publisher as Electronic Arts. This relationship allows us to capitalize on our investments to market and sell downloadable content online, as well as through our network of stores worldwide."

It's safe to say GameStop didn't get much in return for embracing Project $10. EA told investors that in its first wave of Project $10 titles (Mass Effect 2, Dragon Age: Origins and Battlefield: Bad Company 2), 70% of players redeemed the one-time use code for the extra DLC. As for the number who purchased the DLC used because they didn't have the code, EA COO John Schappert said it was "a low single-digit percentage." Consider how many of those customers would have just purchased the DLC digitally instead of going to a GameStop store to buy a code and give the retailer a cut, and it's difficult to see much upside.

Regardless of whether Project $10 was going to help revenues, GameStop COO J. Paul Raines assured investors it at least wouldn't hurt profit margins, saying, "We support the creation of added downloadable content for popular franchises, as we see that as extending the life of titles and broadening the base of game players. We do not anticipate an impact to our used margins due to this program."

The phrase "due to this program" is doing a lot of work there. Project $10 and Online Pass-like programs are just a couple factors that have contributed to the erosion of the used games market in the past decade.

Between that, free-to-play games, digital distribution (and the deep discounts it allows), games-as-a-service models that keep players engaged with games for months or even years, "physical" games that still require gigantic downloads anyway, the rise of physical games as a collectible keepsake people will actually pay a premium for, and any of a dozen other trends, it's difficult to say how much damage each one has done. And that's to say nothing of the deteriorating in-store experience of going to GameStop and being badgered by employees bombarding you with mandatory scripted sales pitches.

Nevertheless, since Raines talked about the company's profit margins on used games as the important thing, I figured it would be interesting to look through the company's last decade of financial reports and see how it's doing on that front. As you might have guessed, the numbers aren't great.

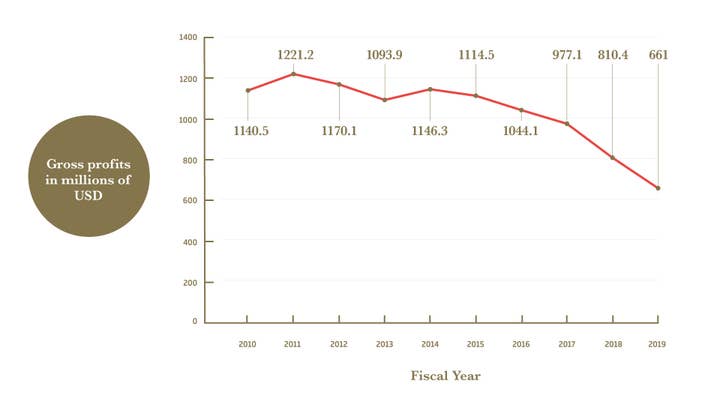

First of all, GameStop's total used sales have been steadily decreasing from a 2011 high of $2.62 billion to about $1.87 billion in 2018, down about 29% over that span. The retailer's gross profits from second-hand sales have eroded even further, trending downward since 2011's $1.22 billion high to 2018's $810.4 million, a decline of 34%.

You might be wondering why I'm cutting off those comparisons at 2018, perhaps assuming I'm not including them because 2019's figures reverse the trend and undermine my point. (No offense taken; I'd be thinking the same thing.) It's actually because GameStop changed the way it reports its earnings in the fourth quarter of last year and no longer reports its used revenues and profits separate from new hardware and software numbers.

However, we can get a good idea of where they were headed from the company's first three quarters, and the answer is basically "down." Through three quarters of its fiscal 2019, GameStop's gross profits on used products totalled $480.6 million, down more than 18% year-over-year. If we assume the fourth quarter sales kept that same pace, 2019's gross profits would have come in at $661 million. In short, the high-margin used game business that has been the heart of the company for so long is today barely more than half of what it was in 2011.

One thing to note about the decline in second-hand sales is that they are down sharply despite console cycle dynamics that should be boosting them. There was one year since 2011 where used sales and profits actually grew for the company, and that was 2014, the first full year with the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One on shelves. In that year's annual report, GameStop said its gross profit on used products was actually worse than it should have been because it was dealing more in next-gen game products, which "carry lower margins early in the console cycle compared to the prior generation products."

In explaining its change of reporting, GameStop only told investors, "We have revised the categories of our similar products, as presented below, to better align with management's view of the business."

Presumably, management has seen the used market evaporating, knows how damning that is considering the company's entire business model has revolved around it for decades, and doesn't expect it to bounce back anytime soon.

A more charitable view might be that GameStop's management knows it can't center the company on second-hand products any more, and if it wants to be around in another 10 years, it will have to learn to build its business on other revenue sources.

In the big picture, I think this is where the industry was heading anyway, even without Project $10. But given that initiative was devised by companies that spent the past generation eating away at everything that allowed a second-hand market for games to exist, this still looks like a mission accomplished to me.

Even so, if GameStop can't adapt to this new increasingly digital reality, I do wonder how much the industry might miss having a major brick-and-mortar retail partner dedicated to its products.

Good Call, Bad Call

GOOD CALL: In this story about Rebellion shuttering its Derby subsidiary and stiffing staffers on their last month's worth of pay as well as layoff packages, industry lawyer Jas Purewal explains how the structure of the business let Rebellion walk away from those debts free and clear, then notes the then-recent lawsuit dozens of Infinity Ward employers filed against Activision over unpaid bonuseslawsuit dozens of Infinity Ward employers filed against Activision over unpaid bonuses.

"There is a theme here of an increasing awareness amongst games developers that receiving payment for their work is not necessarily set in stone - it can be affected by other developments," Purewal said.

His observation remains sadly relevant.

BAD CALL: Ubisoft CEO Yves Guillemot predicted that by 2012, 50% of games on next-gen consoles would be 3D. There certainly was a surge of them in 2010 and 2011, and if you want to count the 3DS as a next-gen console, then that helps a bit, but I'm going to go out on a limb and say this did not happen. 3D was pretty clearly a declining fad by 2012 with TV manufacturers starting to ramp up the push for 4K displays over 3D. At least Guillemot wasn't alone in wildly overestimating 3D gaming.

BAD CALL: The aforementioned Doug Creutz of Cowen and Company noted strong consumer interest in Red Dead Redemption and nearly doubled his sales estimates for the game, saying it could sell 4 million units worldwide in its first year on shelves. I put this down as a bad call only because he needed to get closer to quadrupling his original estimate. Red Dead Redemption sold-in 6.9 million copies in a month and a half, and more than 8 million in its first year.

BETTER CALL: In the same article, Creutz said, "Although this positions Red Dead to be another core franchise for Take-Two, given the time between Rockstar franchise iterations, it is possible we might not see another Red Dead title until the next console cycle." Red Dead Redemption 2 launched in 2018, five years into the next console cycle. (Six if you count the Wii U starting the cycle.)

BAD CALL: EA Mobile's vice president of publishing Luca Pagano looked at the launch of the iPad and how the tablet versions of some apps were asking a premium and concluded that this could stop the race-to-the-bottom pricing that had hampered iPhone developers.

"In a way the iPad will be less crowded on the marketplace compared to the iPhone," Pagano said. "The production values expected will be higher from consumers and I don't think there will be as much downward pressure on prices of apps for the iPad."

He added, "It's very early days but I would expect an even more niche and premium audience. Definitely people with a high disposable income, especially those that have the device in the beginning."

Yes, because who could have guessed that people who spend obscene amounts of money on a luxury Apple mobile product would then cheap out on the apps they use?

GOOD CALL: Who could have guessed? Ed Lea, chief technical officer for Grapple Mobile and person with a good grasp of consumer and developer behavior, that's who.

Lea warned that the iPad wasn't suddenly going to solve the problems facing mobile developers, partly because apps would require more time and effort to tailor for the device, and partly because history repeats itself.

"I suspect that as we saw with iPhone, the price of apps will fall over time," he said. "Copycat apps will start to appear, taking the functionality of successful apps and reproducing them, often at lower price-points to the detriment of the quality of the apps."