Games vs. Guns: How the ESA outspends the NRA on lobbying

Former NRA and MPAA lobbyists talk tactics, explain the ins and outs of political clout, and why official numbers don't tell the whole story

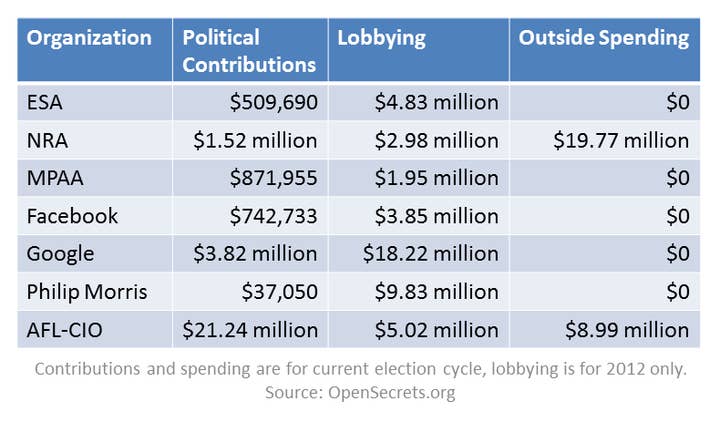

Here's a fun fact: The Entertainment Software Association spends more on federal lobbying than the National Rifle Association. According to the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP), the ESA reported $4.83 million in federal lobbying last year, compared to $2.98 million from the NRA. So why does legislation to keep violent games out of the wrong hands make it all the way to the Supreme Court while any effort to keep guns out of the wrong hands is a non-starter?

Part of the reason is those numbers tell only a fraction of the story. On OpenSecrets.org, the CRP tracks three big areas of political spending: lobbying, contributions, and outside spending. Contributions include money donated to candidates for office and political action committees, while outside spending is money spent on TV spots, mass mailings, robocalls, and other communications. It's in those two areas where the NRA far outstrips the ESA, with the gun lobby spending $1.52 million on contributions in the current election cycle compared to the ESA's $510,000. The difference in outside spending is considerably more dramatic, with the NRA's $19.77 million spent on communications infinitely outpacing the ESA, which hasn't reported a dime in outside spending in the past three election cycles.

But even these figures need to be taken with a grain of salt. GamesIndustry International spoke with Richard J. Feldman, former NRA political director and current president of the Independent Firearm Owners Association, to get some perspective on the subject.

"You can report everything you do as lobbying, but the requirement to do so is much more limited," Feldman explained. "If you send money or have a flier urging support of, say, Senate Bill 25, it's lobbying. If you send fliers talking about the issue but not the specific bill, it's not lobbying... So I might think I'm lobbying. You might think I'm lobbying. But I'm not required to report it unless I'm lobbying for specific legislation."

Organizations can also fudge the numbers on lobbying reporting. Feldman said some groups might consider the salaries of certain employees to be lobbying expenses, while others might not. Some organizations could reveal as much lobbying activity as possible "to puff themselves up," while others might prefer to be more selective in their reporting.

Robert Maguire, a researcher with the Center for Responsive Politics said limited transparency into the lobbying process not only caps the information the public receives, but also makes it difficult to say just how significant that information is.

"In a lot of cases, it depends," Maguire said. "It's always a hassle getting the relevant information to the public in a timely manner. And in this case, it's also a matter of trying to quantify the effect that a group had on a bill they were trying to influence, either at the state level or the federal level. It's hard to say. I'm inclined to say that's where the journalist comes in. You have to look at the data that's there, the issues they tried to influence in general. There are a lot of groups that spend a ton of money and appear to be tragically ineffective. There are others that spend a lot of money and seem to be very effective."

We looked at the political spending of a handful of well-known organizations and detailed them in the table below. The amount of influence a group is perceived to have in Washington, D.C. is not always proportionate to how much it reports spending, and these organizations' strategies on where to focus their resources differ greatly.

Making (Up) the Grade

The criteria for effective lobbying can be as difficult to nail down as the amount spent. For example, the ESA's lobbying on free speech issues did little to impede the passage of a California law that would have made it illegal to sell violent games to children, or to dissuade the state from pushing the law all the way to the Supreme Court, even after lower court decisions came down in the industry's favor. Former Motion Picture Association of America director of federal affairs and current National Music Publishers' Association SVP of government affairs Christopher Cylke said situations like that simply happen sometimes.

"It's just the nature of how congress and legislatures work," Cylke said. "You know the bill's going to pass and there's immediately going to be a lawsuit filed against it and ultimately it will be decided by the court. I don't know if that can be considered a failure on the part of the industry groups that were involved, or in some cases, perhaps the legislators or the bodies that enacted the law. In this case, I think probably many of them knew it was on constitutionally shaky ground, but they did it anyway. And the system played out I guess as people would expect."

The criteria for success also vary depending on who's doing the lobbying, and how much clout they should be expected to have.

"There are organizations out there, groups with specific agendas where maybe even getting someone to introduce their bill is a victory, or getting a hearing on their bill," Cylke said. "Getting a bill signed into law by the President and through both houses of Congress is really a multi-year endeavor for them to try to accomplish, but the industries I've worked for have always had a good record of success, so the expectations are always a little higher."

For the NRA, even failure could be a success. Feldman said the group would give money to candidates who were surefire losers if their opponents had been vocally against the NRA's interests.

"Legislative and political winning isn't about stopping it; it's about preventing them from getting to legislation, from putting you out of business."

Richard J. Feldman

"We would support them to make it as difficult as possible," Feldman said, "because we wanted [political opponents] to know there would be a price to pay."

One thing that Feldman never considered a criteria for success was winning the debate once and for all.

"It never stops," Feldman said. "If you're asking how to put an end to it, that's the wrong question. Legislative and political winning isn't about stopping it; it's about preventing them from getting to legislation, from putting you out of business. It's never about stopping those who'd like to put you out of business, just making it less and less possible for them to pass the laws."

Any contentious issue is going to have industry supporters and detractors in entrenched positions, Feldman said. In his case, he knew people who liked guns would always support the gun industry, and those who hated guns would never come around.

"It's not about influencing your friends or your enemies," Feldman said. "It's about influencing people who aren't one or the other. If you can push some of the middle group into your camp politically, you get called the winner. That's where the game's fought. It's not amongst your supporters or your opponents; it's in the middle."

An NRA Role-Playing Game

When asked what he would do if he were handling the game industry's lobbying efforts, Feldman detailed a number of strategies the ESA has already employed in various forms, as well as the thinking behind them. He first suggested borrowing a page from the MPAA's book, noting that it was very successful at deflecting criticism when it implemented the original version of its ratings system in the 1960s.

"It didn't affect their bottom line," Feldman said. "If anything it was just the opposite. A movie that has an R, everybody wanted to see it because it must be good. They were very successful at deflecting while at the same time being quite upfront and truthful about what was in the film and the product. Sometimes people want to reinvent the wheel and you can look at allied industries, what they did successfully, and morph it to work in today's world, to do what they did as a starting point."

Feldman also stressed how important it was to be seen as part of the solution instead of the problem when an industry comes under criticism.

"Instead of taking an NRA approach with, 'If anybody proposes anything, just say no...' Well, that sets you up as a boogeyman," Feldman said. "It's better to say no, then put forth your own proposal. Now you're part of the process. Instead of saying, 'That won't work, I'm against it,' well, what are you for? What do you propose? If you've got something that will work for you, do it partially to deflect critics, and partially because it makes sense, it works, and takes you out of the line of fire."

"People say, 'Well gee, that could affect sales.' Nothing affects sales, except having your product restricted by law."

Richard J. Feldman

If an industry has already addressed an issue, then it's harder for legislation essentially duplicating those efforts to get traction or support. He pointed to government having to mandate seatbelts in cars for the auto industry, saying it could have been easier for the automakers if they had provided them in every car anyway. (It's worth noting that embracing new standards voluntarily won't always prevent government regulation. In 2008, New York passed a law requiring all new consoles--but not PCs or handhelds--sold in the state to have parental lockout features, even though every console on the market already had the feature.)

"Once you are looking for the solution, you can find the sweet spot in the industry that people are comfortable with," Feldman said. "And people say, 'Well gee, that could affect sales.' Nothing affects sales, except having your product restricted by law. When you do something on your own, you're the good guys. You're trying to fix the problem. Who knows the industry better than your industry? Not the government, not the regulators, not your opponents. They'll be happy to come up with ideas, always. Ban them. Outlaw them."

It's not enough to simply suggest these solutions, however. Feldman said it would also be important for the ESA to let people know it was taking steps.

"I'd go out there and keep representing the manufacturers on TV shows, on radio shows," Feldman said. "I'd go out speaking on Diane Rehm and National Public Radio, which is a great place to do it. I'd be putting stories up in different places and doing the whole social media bit about what we're doing. Being proactive isn't just a matter of coming up with something that works. It's as much about informing everyone about what you're doing as it is having come up with it."

"Good effective lobbying in my view starts way before you have a problem."

Christopher Cylke

Cylke also endorsed the "proactive" approach, saying the groundwork of crisis management is laid before an actual crisis.

"Good effective lobbying in my view starts way before you have a problem," Cylke said, "and I tip my hat to the folks at the ESA. I've worked very closely with them on a lot of different issues, and they have a tough job ahead of them. But those in the movie industry and other industries come under fire, either rightly or wrongly, when situations crop up. If you've done your homework, if you've gone in and introduced yourself to relevant members of congress who will be making decisions and looking at your industry, and you've explained to them exactly why your industry is important to the US, to the economy, to them specifically, and answered some of the questions you think may come up pre-emptively, you have a much better chance of success."

Secret Weapons

As with many strategic games, lobbying has multiple moving parts, and no shortage of pawns. Feldman said his greatest asset in his career has been his relationships in the media.

"I don't deal with the media from the perspective of them being the enemy," Feldman explained. "I look at you guys very much the way I look at a gun. They're both tools that, when used properly, can be very useful. Helpful. Fun! And when used improperly, they can both be very dangerous. It's not the product per se, it's how and who is using it for what purpose."

Cylke listed his employers as one of the big advantages he's had in his career.

"When you're in any of the various entertainment sectors, you have a lot going for you," Cylke said. "You have a high profile. You have a cool product that staffers and even members on the Hill are interested in and interested in learning about. When you pick up the phone from the MPAA or someone in the music world, people return your call. You have a lot going for you and it's just capitalizing on that, establishing the important relationships, and making sure people think twice or at least consult with you so you can go into damage control before they do something that's destructive to the industry or could paint the industry in a bad light."

Conflicts of Interest

Representing an entertainment industry also guarantees plenty of grassroots support when it comes to free speech issues. The ESA's Video Game Voters Network has over 500,000 members that it marshals to contact their legislators and otherwise make the industry's case to family and friends. However, free speech isn't the only issue on which these trade groups lobby. Intellectual property is another big concern for entertainment industry trade groups, and measures like the Stop Online Piracy Act will from time to time put them at odds with the interests of their customers.

The ESA pushed for passage of SOPA, which would have given copyright holders a government-backed right to shut down websites which are hosting copyright infringing material. It was intended to target torrent and pirate sites, but its language left critics concerned the actual powers granted would be far more broadly applied. After much criticism, the ESA finally retracted its support for SOPA, but only after the bill's original sponsors had already given up on it.

"Trust me, I was right in the middle of the whole SOPA thing, and it was not something I'd ever like to relive."

Christopher Cylke

"Trust me, I was right in the middle of the whole SOPA thing, and it was not something I'd ever like to relive," Cylke said. "I'll avoid going into any of the details on my feelings about what exactly happened there. But there certainly is sometimes a tension, and there are other groups out there as well fanning the flames and pushing customers in another direction, saying 'Hey, these folks are screwing you.' That's why I think it's effective and a good policy and strategy for industry organizations like the music, movie, and gaming industry, frankly, to go directly to their customers sometimes and say, 'This is what we're doing, this is why we're doing it, and ultimately, this is the benefit to you.'"

Cylke said that means talking about legal services that are available to customers, as well as steps the industries have made in recent years. That's a message he said has resonated with legislators, and it's one he hopes will resonate with customers "when they get to see the long view of everything."

"Post-SOPA, and I don't think I'm telling any big secrets here, there was definitely a lot of looking in the mirror and assessing what went wrong and how not to make those mistakes again. So there was very much a shift from talking about piracy, which I think is still a big concern for the groups, and much more of a shift in rhetoric toward talking about the positive things the industry was doing to meet consumer demand, both in the music and movie space."

But much like Feldman, Cylke doesn't expect to make converts of the staunchest detractors.

"I think there's always going to be a hardcore group of folks out there who don't like the RIAA, the MPAA, the ESA, or anybody who tries to do certain things in the copyright space related to digital rights management," Cylke said. "It's just the nature of the way the Internet operates now."

The ESA did not respond to interview requests for this feature.