"Gamers are bored... They're ready to spend on something new"

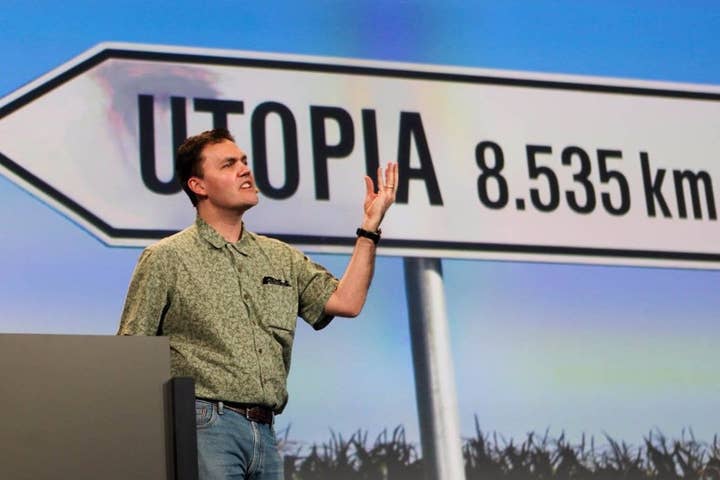

Jesse Schell has waited 25 years for consumer VR to arrive, and he has a few theories about how the market will take shape

After years of relentless campaigning, even VR's true believers could be forgiven a little fatigue. Maintaining that level of enthusiasm on little more than utopian rhetoric and five-minute demos is no small task, and now that two of the three main contenders are available to consumers - in theory, anyway - the line between idealism and pragmatism will become inescapably clear.

Few in the industry are more eager to trace the arc of that line than Jesse Schell. Until John Carmack showed up at E3 with the duct-taped prototype that would become the Oculus Rift, most people's knowledge of VR will have been through one of the many half-hearted attempts that now reside in the industry's murky past. Schell, however, has been dedicated to virtual reality's evolution and implications for nearly 25 years, starting with a master's thesis on networked VR in 1992, via the creation of Aladdin's Magic Carpet Ride for Disney in 1995, to the VR-oriented teaching post he has held at Carnegie Mellon since 2002.

"We haven't had anything really new and exciting happen in gaming in, like, five years"

"We thought it was gonna happen way faster than it actually happened," he says. "I fully believed that in-home VR systems would be a normal thing by round about mid-2005, but even as we worked with the technology more and more it was still expensive, and it wasn't quite ready. It took longer than we thought."

To say that Jesse Schell has been waiting a long time for VR to arrive is to diminish the truth. When I mention my first meeting with Palmer Luckey, at a poorly attended London conference months before the Rift even hit KickStarter, Schell laughs warmly. "Was he delivering newspapers? The guy sells a company for $2 billion and has to wait six months to have a beer to celebrate. That's messed up."

Schell compares VR in 2016 to television in 1948. At that point, the people who were aware of TV would have assumed it was invented a few years before; according to Schell, it had existed in various forms since 1890. "You can imagine somebody in 1942 being asked to invest in television," Schell says, before wrinkling his nose in mock-disgust. "'Ugh, are you kidding? We tried that. That doesn't work.' But when the technology gets to a certain point everything clicks. That's what finally happened.

"We've turned a corner with VR technology. It now engages people psychologically in a way that it didn't before."

That much is certainly true, but we're now at the point where we should regard the parade of impressive demos down the years as distinct and separate from VR as a consumer product. Blowing a person's mind for ten minutes at a developer conference or game expo is entirely different from asking that same person to bring a head-mounted device weighing half-a-kilo into their home, and to find a place in their daily lives for the isolating experiences that are its speciality. And to then weigh both of those concerns against a total outlay that - including PC hardware, in the case of the Rift and the Vive - is likely to top $1,500 for several years to come.

"Apple has trained people not to spend money on mobile. It's a great deal from Apple's perspective"

Schell admits that the difference between knockout free demos and actually selling that same experience presents, "a complex question," but he sees two factors that will allow VR to gather momentum. "One is: gamers are bored," he says. "We haven't had anything really new and exciting happen in gaming in, like, five years. Gamers are ready for something new. They're hungry for it and they're ready to spend on something new.

"Second, this feeling of presence is a thing that most people haven't experienced. It's going to be the thing that everybody is talking about. We're going to see a slow expansion out into the world... but people are going to be so viral about it, because when people have a good VR experience it's like they get religion. They can't stop talking about it."

Schell's second point implies a problem for the Samsung Gear VR, a budget friendly option that most would agree doesn't deliver the kind of heady experience that sends the user into a slack-jawed reverie. It is still VR, yes, but it is diet, caffeine-free VR, arguably lacking the viral appeal to convince users that the technology demands a greater personal investment. And that could be crucial in its immediate future as a commercially viable platform for developers, because, in Schell's view, spending habits on Gear VR will mirror spending habits on mobile.

"Apple has trained people not to spend money on mobile," he says. "It's a great deal from Apple's perspective: we'll sell you an $800 phone and give you lots of software for free. People like that, so they do it. But when they use that same phone for VR they expect that same deal. I don't think you're gonna be able to beat that [association]. I believe the serious revenue is going to be in the high-end stuff, because people are willing to spend.

"If I had to guess, over the next three to four years, I think VR revenue is going to be people paying for premium experiences, as opposed to your current free-to-play, 99-cent experiences. I could end up wrong about that, but that's what I think."

"When people have a good VR experience it's like they get religion. They can't stop talking about it"

This raises the further question of whether there will be a viable casual audience for VR at any point in that same period. Samsung Gear VR would certainly be the obvious platform for the casual market, but the business model those players prefer normally requires scale to work effectively. Indeed, Schell highlights in-game payments as a problem for VR in terms of user experience, too. "Everybody's going to try [microtransactions] because everybody's going to try everything," he says. "The problem with it is that the payment moment is a presence breaker. That's not great."

Schell refers to his former employer, Disney, which charged its customers on a per-ride basis when it first opened its theme park. The idea of including every attraction under a single ticket was first introduced by a competitor, Magic Mountain, and the improvement to the customer experience was so immediate that Disney soon followed. When the fantasy is so carefully crafted, and the illusion so delicately balanced, why spoil it with economics? Schell concedes that there will be a place for microtransactions, but not necessarily at the top table. "Premium payments are going to dominate in VR," he says.

If the majority of revenue over the next few years will be earned from premium experiences on high-end headsets (Rift, Vive, PlayStation VR), a great deal rests on the size of the installed base those platforms can build. Developers have been committed to VR since Oculus started taking Kickstarter donations for the DK1 in 2012, and that community has grown exponentially in the time since. A great many studios have been working on nothing but VR products for two or three years. They now have a chance to recoup that investment, but it's very hard to put a price on the experiences they are selling. VR's fundamental connection to PC (Rift, Vive) and mobile (Gear VR) also fundamentally connects it to the spending habits of users on those platforms. Earlier this month, GI contributor Rob Fahey addressed the consumer response to the perceived high price of VR software, observing that the market, "isn't going to be immune to the price pressure which has, in recent years, seen the price of games on Steam decline rapidly, and made it nigh-on impossible to make money from anything other than F2P titles on mobile."

"I believe the serious revenue is going to be in the high-end stuff, because people are willing to spend"

There is anecdotal evidence of this already, with developers attempting to monetise short experiences created in VR's demo era attracting criticism from users, and Owlchemy Labs choosing to cut the price of the widely promoted Vive exclusive Job Simulator by $10 after just a fortnight on sale. This may have been due to a slower than expected start: SteamSpy's data indicates that Job Simulator has fewer than 8,000 owners; Audioshield, one of the most popular Vive games, has around 25,000 owners. Whether those figures are good, bad or indifferent depends on a variety of factors, but they are certainly small enough to suggest that targeting multiple platforms will be the smartest play.

For Schell, however, quality of experience is paramount to creating the viral enthusiasm that will drive adoption of the technology. The best way to accomplish that, he says, is to be honest about how different the market's key players have become. "Even the difference between the Vive controllers and the Oculus controllers. There's enough difference there you really have to stop and think. There's a lot of subtle details.

"Focus in on one platform. Optimise for that platform and make it great there, and once you've succeeded there, then take a step back and think. You're welcome to call this 'Schell's Law of Adaptation,' because it's not just true for VR, it's true for everything. Would Harry Potter have been better if they did the book and the movies at the same time? It wouldn't. Let it grow strong as one thing, and then adapt it."