Four years and 70 issues later: Why Wireframe magazine is closing down

We catch up with editor Ryan Lambie to discuss the magazine’s life and demise

At one point in time – many years ago now – it was probably a shock when print publications were closed down. These days, that is sadly not true.

Over recent years, we’ve seen countless game magazines shutting their doors. Usually, it’s for the same reason: circulation dropping as a result of people preferring to read coverage online or in video form.

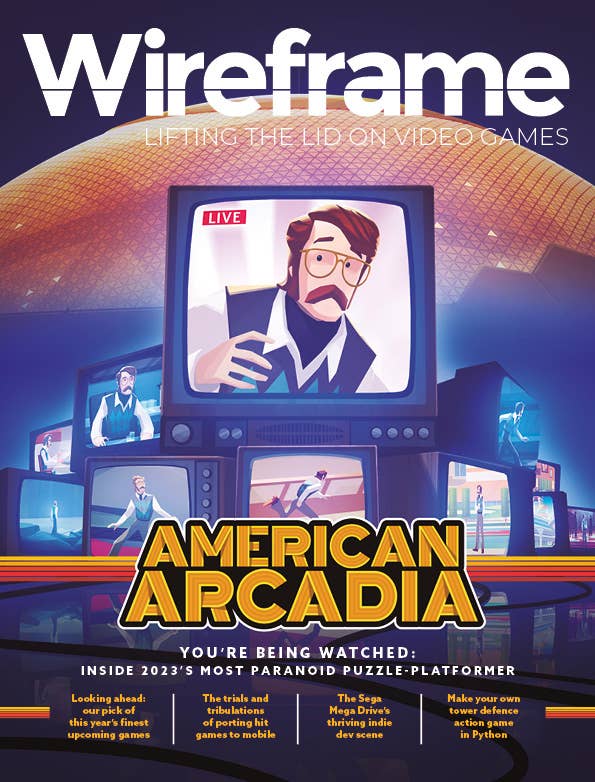

The latest print publication to bite the dust is Wireframe. Founded back in 2018 by Raspberry Pi, the magazine managed to release 70 issues – 38 fortnightly, a further 32 monthly – before calling time at the start of the year.

As for why it will no longer be releasing a physical edition, it’s much the same story, with some decidedly contemporary twists.

“It's a mixture of things really,” editor Ryan Lambie tells GamesIndustry.biz.

“It's been a tough couple of years for everyone in print. We came out of COVID, and the lockdowns had harmed shop and newsstand sales. The footfall outside places never really recovered once the world unlocked again. Now we have the cost-of-living crisis as well, so we've seen print costs shoot up. Distribution is more expensive, too.

“And then, of course, people are making cutbacks on expenditures like magazine subscriptions. It's all sorts of things. Everything's become so expensive. It's pretty much the perfect storm, really. It's become more expensive to produce a magazine, while fewer and fewer people can afford the luxury of spending £6 a month per issue, or £45 a year on a subscription.”

To give an indication as to how the cost-of-living crisis has impacted Wireframe in particular, Lambie reckons that subscriptions for the magazine have dropped by something like 35% compared to before COVID. That’s also where the majority of the publication’s revenue came from, too.

The margins on print publications have always been tight, though the increased costs involved these days have meant that it’s simply untenable to produce a Wireframe magazine anymore.

“If you just look at the raw cost of printing a magazine, I'd say it's doubled,” Lambie explains. “So – this is just all 'back of a cigarette packet' maths – if a year or 18 months ago it cost £1 to produce a magazine, now it costs something like £2. The margin on magazines is always tight anyway. By the time you actually send it out or what you've done subscription offers and all these things, it's always tight. Once you have once you factor that into people tightening their belts, it's always going to have an impact.”

As a result, Lambie isn’t what you’d call optimistic when it comes to the print landscape in general.

"There are ways to save costs with magazines - reduce your page count or the quality of your paper - but there are only so many cuts you can make"

“It's going to be tough,” he says. “I think different places will handle it in different ways. There are ways to save costs with magazines; you reduce your page count, and you reduce the quality of your paper stock to go with something thinner and lighter. That means it's cheaper to move around. But there are only so many cuts you can make. It wouldn't surprise me if we saw other magazines closing their doors, but it's hard to say. It's definitely going to be tough for everyone in the next few months.”

Regardless of where Wireframe has ended up, 70 issues of a print magazine – especially given media industry conditions in a post-internet world – is no small feat. It’s especially decent when you consider that the publication started life in 2018, the year in which Future Publishing closed down long-running brands like GamesMaster and GamesTM.

“I think we succeeded in making something that's a little bit different,” Lambie says.

“The support for it has been really fantastic. It has a really great community. One of the silver linings actually of the print side going away is the response we’ve had. It’s been fantastic to see. Four years is good, 70 issues... I think we had a really good run.”

He continues: “By the time we had launched, it was only a few weeks after GamesTM and GamesMaster both closed their doors, which was incredibly sad. I absolutely loved GamesTM. It was a bit of a funny time because our hope was that we weren't trying to be the 'all things to all people' games magazine of the 90s or early 00s, where you try and cover all the big AAA stuff. We very consciously focused more on indies, the development side of things and the DIY angle.

"We knew that we would find a niche and for a very long time, we did. We have a great community of people that do love the magazines and love the style of it and that's something we definitely want to continue.”

Wireframe is somewhat similar to Future’s Edge, in that it targets people within the games industry, as well as those who would like to be in it – the so-called ‘prosumers’. But the Raspberry Pi-backed publication had more of a focus on showing people they could make games themselves.

“The DIY aspect of Wireframe was so important,” Lambie says. “The idea is that you read it as a gamer, but it's telling you over and over again that you can do this, too. It's trying to demystify the various aspects of game design, whether that's narrative or programming or building things in Unity.

“That's why we had the Toolbox section in the middle of the magazine. You don't have to get into it if you don't want to – there's the stuff you expect to find in a games magazine, such as the features, previews and so on – but in the middle there, there was this whole section waiting for you that demystifies games and shows you that you can make stuff too. That's one of the things that people responded really well to.

"Every issue, we gave a solo dev a spotlight and the stories would be really inspiring"

"A few months ago, think it was in November, we just published a digital bookazine. It was a compilation of all the little snippets of code that we'd had in the last couple of years; there was a selection where you could make scenes or mechanics from arcade games. We had a good 100,000 downloads. Obviously, that hit a chord with people.”

In some ways, Wireframe is the continuation of the '80s DIY games scene; back when magazines and TV shows about the burgeoning medium would feature code so that viewers and readers could create games on their own computers.

“That was one of the things I talked about before the magazine launched,” Lambie says. “It'd be really fun to revisit that '80s games magazine hobbyist style, but for the 21st century. All the code and the asset files and everything are there on GitHub if people just want to download them. They don't need to sit there and type it out. They’ve still got this tutorial, this mini guide that's in paper form, that they can just sit and digest. It's a really good way of learning how to program actually. That was something I was keen to bring back.”

The DIY focus is clearly something that Lambie is happy with, but his biggest source of pride when it comes to Wireframe is its focus on indie developers. What that term means really depends on your perspective, but in this case it’s one-person projects.

“One of the things we always did in every issue is making sure we have coverage of this one game that was made by a solo developer,” he says. “Giving them a spotlight and somewhere where they could talk about their experiences. For every issue, we would give them a spotlight and the stories that we got from some of them would be really inspiring.

"You had people that were up at like two in the morning with the baby sleeping next to them, they're programming a game. You had the people who were just completely burnt out because they've worked so hard and put the game on Steam, only for it to just not sell. To be able to create a spotlight for those stories and those individuals something I’m really proud of.”

Another factor in Wireframe’s relatively long life was that it wasn’t subject to some of the same pressures that other print magazines were. Sure it needed to make money, but that wasn’t as much of a concern as other publishing houses. Wireframe had the backing of Raspberry Pi Ltd, which acted as a kind of marketing for that company.

“The point of Wireframe, MagPi and Hackspace is partly as an expansion of the Raspberry Pi brand,” Lambie explains. “They're a good way of illustrating the Raspberry Pi mission and ethos of the product is the love of the computer. It is a bit different from a traditional publishing company, which is purely focused on sales, revenue, and things like that. There is a difference, certainly.”

"Sure you can listen to all the music you want on Spotify, but there's something nice about a physical product"

As well as a physical magazine, Wireframe could also be purchased online as a PDF. What’s more, readers could pay what they wanted – even nothing at all.

“I think magazines are a little bit like vinyl,” Lambie says. “Sure you can have an mp3, you can have Spotify or whatever, and listen to all the music that you want, but there's also something nice about having a physical product.

"There's the magazine for people for the people that want the physical product, which I'd say is definitely the best way of experiencing the magazine as it was. Part of the Raspberry Pi ethos is accessibility and making things available to as many people as possible. Releasing the magazine as a creative commons PDF meant that money wasn't a barrier to reading it.”

While in theory, this might act like a demo to entice people into paying for the magazine, Lambie says that the traffic was “bi-directional” on this front.

“Sometimes we would have people saying, they'd been downloading the PDF and loved it so much they wanted to subscribe and support the magazine that way,” Lambie says.

“Then sometimes people would say as much as they want the magazine, they're running out of space and going to switch over to the PDF. So it was a mixture really.”

Though the Wireframe print magazine is closing down, the brand is not done yet.

In its message to readers, the publication said that it was going to be continuing as an online-only brand. It’s early days yet, so there isn’t much that Lambie can say on the matter, but it’s safe to say we can expect more of the same from Wireframe.

“The big hope is that we keep the same ethos going, just online,” he says. “Hopefully we'll be able to produce a PDF version of the magazine periodically. Nothing is set in stone yet, it’s still all being worked out. That's all I can say at the moment.”

Sign up for the GI Daily here to get the biggest news straight to your inbox