Everybody hates Zynga | 10 Years Ago This Month

The social gaming giant hits rock bottom, decides to set up camp and stay there for a while

Zynga always had its detractors, being a poster child for the social gaming boom that some traditional developers and players found derivative, exploitive, or just plain evil.

But a decade ago, the social gaming giant had become a punching bag for essentially anyone and everyone. It was already in a precarious spot, suffering from a deflating Facebook social gaming bubble and struggling to build up much of a presence in mobile gaming to offset those losses. But the sentiment around the company got notably worse starting with a handful of developments in the last week of July.

First (and, if we're being honest, foremost), the company stumbled financially. This industry will forgive a lot if you're making money – hello, Activision Blizzard board of directors – but no profit margin means no margin for error.

So when Zynga's second financial report since its IPO fell far short of expectations, a sell-off of company stock dropped the price below $3.33, less than one-third of what it initially traded for the previous December. Not even the earnings call news that the company was getting into real-money gambling could spark optimism around its financial fortunes.

The second hit came just days later, when an investor filed a class-action suit accusing Zynga executives of insider trading, saying they knew the company's outlook was going to take a hit when they unloaded hundreds of millions of dollars of stock earlier in the year.

Finally, Zynga ended July by demoting chief operating officer John Schappert. The timing was odd, as such shifts would ordinarily be made alongside the earnings. If it was related to Schappert's performance, Zynga surely knew about that when it released its numbers.

But Zynga might not have expected such a large drop in its stock price, or the resulting insider trading suit. Schappert was one of the executives named in the suit, having sold $3.9 million worth of stock.

Zynga CEO Marc Pincus was also named, having sold $200 million of stock. (He was not demoted.)

Schappert's demotion was a surprise even with the company underperformance and the suit. He had a track record of success at EA and Microsoft, establishing the Madden NFL and NHL franchises in the '90s at Tiburon, overseeing worldwide publishing and Xbox Live software during the height of the Xbox 360 era, and returning to EA as COO after that. He had also been at Zynga for just over a year.

"Pulling a game guy out of the primary responsibility for managing the game effort, and putting a non-game guy, which is Pincus, in charge, I think that's idiotic," Wedbush analyst Michael Pachter bluntly said in response to the move.

Understandably not enjoying the experience of being scapegoated for the company's woes, Schappert resigned in early August.

The day after Schappert's resignation, Zynga announced that it would be giving all of its employees stock options in what one analyst called "a proactive move to prevent mass exodus."

Zynga's employee retention measure was followed by a frankly hilarious rush of executives to the lifeboats

Stock options are great, of course, but the impact of the move probably would have been greater had management not driven the stock price into the ground in less than a year and cashed out hundreds of millions of dollars worth of stock months earlier because they knew which way it was headed.

I suspect it also didn't help that the company had a historically of unapologetically telling employees they didn't believe "earned" the options to give them back or be fired.

Regardless, that employee retention measure was followed by a frankly hilarious rush of executives to the lifeboats.

Following Schappert out the door by the end of the year were fellow EA alum and chief marketing officer Jeff Karp, chief technology officer Allan Leinwand, chief creative officer Mike Verdu, vice president of studios Bill Mooney, vice president of marketing Brian Birtwistle, former Omgpop chief revenue officer Wilson Kriegel, chief security officer Nils Puhlmann, chief financial officer Dave Wehner, treasurer Mike Gupta, and VP of biz dev Jonathan Flesher.

It got so bad professional courtesy went right out the window and people were just weighing in on someone else's business completely unprompted, one of those things anyone with a minute of media training should be hesitant to do.

A director of Apple was asked to help Pincus become a stronger business leader, and then blabbed to the Wall Street Journal about how the Zynga CEO was nearly in tears about how poorly the company was doing.

In promoting a Kickstarter for a spiritual successor to his seminal hit Pitfall, David Crane said Zynga's games "give the casual market a bad name."

And even though "professional courtesy" was sort of the opposite of Kixeye's brand, it was still odd when CEO Will Harbin touted the poaching of CityVille GM Alan Patmore by saying, "Zynga is about making games for grandmothers. There are a lot of talented game developers at Zynga working on games they don't really care about."

"Zynga's about as stable as Syria right now" EA exec Frank Gibeau

EA Labels president Frank Gibeau went out of his way to take a jab at Zynga in an interview about EA cutting staff at its PopCap division, saying, "We're pivoting hard toward mobile because it is the fastest-growing segment of the interactive games business right now and it's certainly probably pulling most of the activity off social, and that's why you see the flattening in social right now - and frankly where the problem is that Zynga's encountering."

Weeks later in speaking with the LA Times, Gibeau likened the flight of executives from Zynga to a genuine humanitarian crisis, saying, "Zynga's about as stable as Syria right now," in reference to the country's ongoing civil war.

Part of that stance was probably due to EA generally taking a pricklier public demeanor in those days – it would somewhat regularly denigrate Call of Duty when it still had hopes that Battlefield or (snicker) Medal of Honor could take the military first-person shooter throne – but tensions would have been particularly high ten years ago this month in light of EA suing Zynga, alleging that The Ville had shamelessly cloned its own game The Sims Social with the help of confidential information from former EA execs like Schappert and Karp.

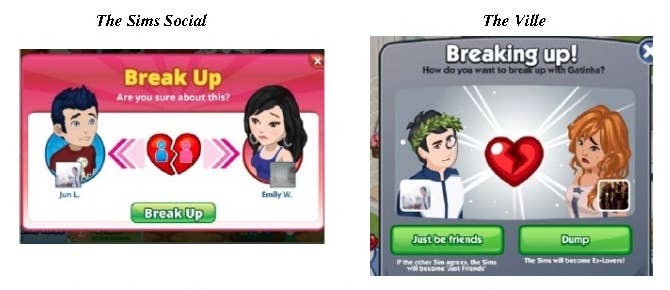

"Zynga's design choices, animations, visual arrangements and character motions and actions have been directly lifted from The Sims Social. The copying was so comprehensive that the two games are, to an uninitiated observer, largely indistinguishable," said EA Maxis general manager Lucy Bradshaw in a blog post about the suit.

The suit itself contained a number of comparison photos showing just how similar the two games were. In fact, in what was either a careless mistake or a brilliant way to make a point, EA's suit actually mislabelled one of its comparisons, specifying a screen of The Ville as coming from The Sims Social and vice versa.

Bradshaw called it "a case of principle." EA's Peter Moore said the publisher was standing up for the industry.

"We've seen enough of it from an industry perspective, with smaller publishers and developers who also put their hands up and said, 'this is not right, but I don't know what to do about it.' We do."

Beyond whatever it hoped to accomplish in court, my guess is that EA – which a few months prior had been named the Worst Company in America in The Consumerist's online poll – also saw a chance to rehabilitate its image, picking a fight with a company so disliked that EA couldn't help but be the good guy in the story.

And Zynga was clearly disliked at the time. Earlier that year, three-person studio Nimblebit had publicly shamed Zynga with an insincere thank you letter for being such big fans of its hit Tiny Tower that Zynga would clone it with its own Dream Heights.

And because this industry has always lacked self-awareness, another social game developer then cloned Nimblebit's letter to thank Zynga for being such big fans of its own game, Bingo Blitz, that it made Zynga Bingo look like… well, bingo. But with a generic-looking social gaming interface on top. (I'm not saying every attack on Zynga was justified. I'm just saying people hated Zynga to the point that EA could look good in comparison.)

As for the lawsuit being a matter of principle and sticking up for smaller developers, EA and Zynga settled it several months later, because of course they did.

And if the lawsuit against Zynga was actually supposed to improve EA's reputation, it didn't even seem to accomplish that. The publisher would retain its Worst Company in America crown the following year.

"I watched alcoholism and substance abuse skyrocket, relationships crumble, people slept on office couches, one nervous breakdown" Anonymous Zynga employee

Getting back to August of 2012, the stock price collapse also led to a number of Zynga employees airing their grievances with the company anonymously. One person said they had been part of a start-up that was acquired by Zynga and made to crunch to get their game finished, and the quote reads like a speedrun of the flood of bad employer investigative pieces we would be seeing in the decade to follow.

"I watched alcoholism and substance abuse skyrocket, relationships crumble (including my own), people slept on office couches, two developers got divorced, one nervous breakdown," said the writer. "They attempted to smooth this over with more stock, free food and t-shirts. Free food doesn't do you much good when you've lost fifteen pounds from not eating."

So Zynga was hated by investors, analysts, developers, publishers, and even its own employees. As a cherry on top, Dartmouth business professor Sydney Finkelstein named Pincus to his annual list of the world's five worst CEOs.

Pincus' losing streak would continue, and he would step back from the CEO position in the middle of 2013, finding his ideal successor in Don Mattrick.

At the time, Mattrick was the head of Microsoft's Xbox business, having been with the company since early in the Xbox 360 generation. Whatever he had contributed to the 360's success felt like ancient history by the time of the Zynga move, as Mattrick was in the middle of fumbling Microsoft's hard-won market share in the console market with arguably the worst hardware launch plan this side of the millennium.

While Microsoft had really only had a handful of moments to show off or talk about the Xbox One by the point Mattrick jumped ship, they had been uniformly botched. Gamers and industry-watchers alike didn't like the initial focus on TV and sports. A chance to salvage things at E3 instead dug Microsoft's hole deeper as the decision to have a mandatory Kinect camera in every bundle and the adoption of unpopular and poorly communicated used game restrictions wound up handing Sony a $100 price advantage and a huge marketing win.

Nevertheless, the announcement of Mattrick joining (or perhaps Pincus stepping down) gave Zynga shares a modest boost, pushing them up to $3.42 as investors hoped for better days ahead. Two years of ongoing losses later, Zynga shares were trading at $2.90, and Mattrick left the company in what the company called "a mutual decision."

When it was announced that Pincus would be taking the helm as CEO again, the stock immediately dipped another 10% to $2.60. (It probably didn't help that Pincus had spent his time away from the CEO spot telling people how bored he was with games, Zynga's included.)

Pincus would do a better job picking his second successor the following year, tapping EA's Frank Gibeau to take over (yes, the Syrian civil war analogy Frank Gibeau) as he once again stepped into the background. Zynga shares soared on the news, skyrocketing 7% to, let's see here… $2.31.

Under Gibeau, Zynga grew revenues relentlessly with a string of acquisitions, and while it wasn't always profitable -- often not even close -- it completed the long-in-the-works turnaround story, rehabilitating both the company's stock price and (for some people, at least) its reputation.

When Take-Two acquired Zynga earlier this year, it paid $9.86 per share in a mix of cash and Take-Two stock, just 14 cents shy of the $10 it went for at its IPO more than a decade ago.

What else happened in August 2012?

● Nintendo got called out for making no effort to ensure the conflict minerals in its products weren't funding human rights abuses. As our annual reports on the subject have chronicled, Nintendo has significantly improved its efforts in recent years.

● With the Wii all but abandoned and the fast-approaching Wii U not looking like a slam dunk success, Nintendo decided to shut down its long-running Nintendo Power magazine. Meanwhile, Future Publishing shut down its unofficial UK mag Nintendo Gamer.

● Sony shut down Studio Liverpool (formerly Psygnosis), closing the doors on the studio responsible for franchises like Lemmings, Wipeout, Shadow of the Beast, and Colony Wars. Later that year a group of Studio Liverpool devs formed a new studio called Firesprite.

Despite closing Studio Liverpool, Sony would turn to Firesprite repeatedly for help with projects like the PS4 launch minigame collection The Playroom, Run Sackboy Run on Vita, and The Playroom VR for PSVR. Sony brought the relationship full circle when it acquired Firesprite last year.

● Amazon Game Studios burst onto the scene with a Facebook game. While it has more recently gained a reputation for troubled large-scale AAA development (even if New World and Lost Ark might finally see it turning the corner), AGS started out with a series of modest mobile and Facebook titles.

● As EA posted a dip in quarterly profits under John Riccitiello, it announced a plan to buy back $500 million in company stock. It would also layoff more than 1,000 employees early in 2013 as its troubles persisted. This is not to be confused with John Riccitiello-led Unity, which laid off hundreds of people this June, announced plans for a $2.5 billion stock buyback in July, and then posted deepening losses earlier this month.

● Id Software legend John Carmack expressed some frustration with life at the studio following its acquisition by Bethesda, particularly in how it backburnered mobile game development.

"It was looked at as something that, yes, this is fun, this is fun for the company and it's entertaining and it makes money, but it's not a grand slam sort of thing on there," Carmack said at QuakeCon. "The Bethesda family really is about swinging for the fences."

Carmack would join Oculus almost exactly a year later specifically because he wouldn't be able to work on VR at Bethesda.

Unfortunately for Carmack, his new employer would also be acquired by a company pushing a vision that didn't mesh with his own. Facebook paid $2 billion for Oculus in 2014, and while Carmack said at the time he believed Facebook got the big picture on VR, his comments last year during a Facebook Connect keynote address about the metaverse suggested that belief did not pan out.

"I have been pretty actively arguing against every single metaverse effort that we have tried to spin up internally in the company, from even pre-acquisition times," Carmack said, adding that the concept was "a honeypot trap for architecture astronauts" who only want to talk about broad concepts instead of worry about the logistical basics of a new technology.

● Pioneering game streaming service OnLive fired all of its employees and sold its operations to one of its earlier investors, which quickly rehired about half the staff at their old salaries. The shuffling allowed the company to wriggle out the vast majority of the $30 million (or more) it owed in debt at the time, with one insolvency service provider in the deal suggesting creditors would get five or ten cents on the dollar owed.

As with the Zynga situation above, the company's financial struggles led to further negative coverage, as former employees burned by the sketchy change in ownership went to The Verge to talk about how paltry the OnLive user base actually was and share stories about micromanaging and petty behavior by majority shareholder and CEO Steve Perlman.

Good Call, Bad Call

BAD CALL: EA Games executive VP Patrick Söderlund predicted the end of boxed games as a viable business, saying, "I think it's going to be sooner than people think. I think it's going to be sooner than ten years."

While the boxed game market has been shrinking for years and it's certainly not advisable for AAA companies (or almost anyone, really) to launch games exclusively as boxed titles, there's clearly still enough demand out there that it makes sense to release games physically as well as digitally.

BAD CALL: Despite the closure of SOCOM developer Zipper Interactive earlier in the year, Sony Worldwide Studios president Shuhei Yoshida insisted the shooter franchise was not dead, saying, "It's not done. We never retire any franchise."

While Sony could always return to SOCOM at some point in the future, we've gone 10 years without a peep now and if we are to believe what Sony is telling Brazilian regulators examining Microsoft's Activision Blizzard acquisition, Sony is so afraid of Call of Duty there's just no point in trying any kind of military shooter as long as Activision Blizzard's franchise is around.

SHOULD HAVE BEEN A GOOD CALL SOONER: After Dragon's Dogma sold 1 million copies, Capcom said it would probably make a sequel. After years of the original game and its Dark Arisen expansion cultivating a reputation as a cult hit, Dragon's Dogma 2 was finally announced earlier this year.

BAD CALL: In introducing a new system that would allow people to buy DLC in-store and set their Xbox 360 downloading it by clicking on an email, GameStop president Tony Bartel explained the benefit to the system was the convenience of not having to input a 25-digit code, as they did with the retailer's previous in-store DLC sales. I mean, sure, that streamlines the process a little, but the convenience pitch will only go so far when you're still making people come into the store to buy something they could just download directly from the console in the first place.

BAD CALL: Bungie founder Alex Seropian mocked the trend of trying to replicate the console dual-stick interface for first-person shooters on mobile platforms.

"A lot of the efforts have been lazy – there have been a lot of straight-up ports from console titles to mobile and a lot of ports of unnecessary concepts," Seropian said. "The transfer of the whole dual sticks thing just amazes me, that anyone would think that's a good idea."

He added, "So much work and research went into making sticks feel good for a shooter that to reinterpret that on a device where you can touch any pixel is just braindead, I don't get that."

Braindead or not, it seems to have worked out pretty well for the PUBG Mobiles, Fortnites, and Call of Duty Mobiles of the world.

BAD CALL: On his way out the door, HMV CEO Simon Fox gave a vote of no confidence in the company, saying he wouldn't bet on the entertainment retailer being around in 2021 to celebrate its 100th anniversary. It was certainly touch-and-go for a while there, but HMV did celebrate its 100th anniversary with (among other things) a free performance by Ed Sheeran at one of its stores, and it continues to get by to this day.

BAD CALL: 2K Games head Christoph Hartmann defended the industry's reliance on violence, saying, "Recreating a Mission Impossible experience in gaming is easy; recreating emotions in Brokeback Mountain is going to be tough, or at least very sensitive in this country... There is only a certain area that you can use [to create games] and then you look at technology, you can kind of maybe make people look right, but it will be very hard to create very deep emotions like sadness or love, things that drive the movies. Until games are photorealistic, it'll be very hard to open up to new genres."

Who knew the asset with the highest polycount of all would be the human heart?