Emily Greer: "New stores are changing the expectation that only Steam matters"

The outgoing Kongregate co-founder discusses the ongoing breakdown of Valve's monopoly, and the need to take a stance against offensive content

Breaking Steam's monopoly on the PC games market was always going to take time, but Kongregate co-founder Emily Greer is optimistic that the process is well underway.

Last week, it was announced Greer is departing the firm after 13 years. Fortunately, GamesIndustry.biz was able to catch up with her back at GDC to discuss the changing landscape of PC games stores.

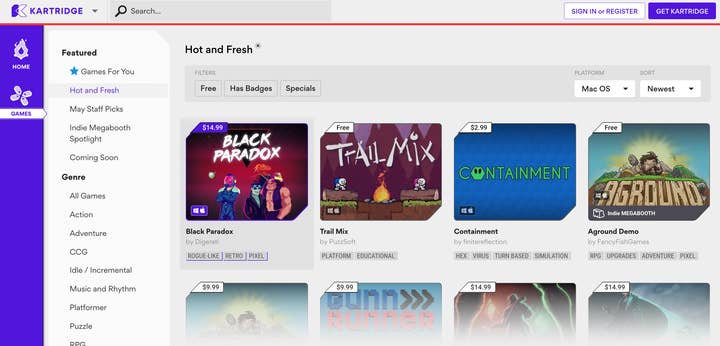

It's been just over a year since Kongregate announced plans for its own digital games marketplace, Kartridge, which -- while not offering the same scale of content as, say, the Epic Games Store -- is still considered alongside Epic and Discord in the conversation about companies loosening Valve's grip on the market.

Although Epic launched its store in earnest back in December, Kartridge remains in open beta and is, "still very much in the development phase." But Greer told us there is no rush when it comes to Kongregate's new venture.

"One thing we know from our past experience is platforms take a while to build," she said. "We built up Kongregate.com over four or five years before everything was at the full level, and whether you're looking at us, Epic, Discord or any of the other things, I think people have this unrealistic expectation that it's going to launch and take half of Steam's revenue -- that's just not how things work."

She compared it to the mobile market, where it took Android, "years before it was an equal competitor to iOS."

Despite Epic's disruption of the PC games market so far, plans for Kartridge have not changed. It will continue to focus on small- to mid-sized indies, with an emphasis on community features and an associated metagame in contrast to Epic's, "deliberately bare bones store."

The marketplace has opened up to free-to-play games, which have unsurprisingly been a big draw. More surprising is that they engage beta users with Kartridge enough to convince them to buy premium titles -- something that underlines a fundamental truth about the PC store wars for Greer.

"People aren't looking for a new platform, but they are looking for new games," she says. "[In our case] it's easier to bring people in with free games and then have them fall in love with the platform."

Greer is also pleased to see Epic has "changed the attention of the space a lot" because it highlights the long-running problems of a PC market that was an "effective monopoly."

"People were just developing for Steam and just had Steam in mind," she said. "As there's a rise of other stores -- and besides the new ones coming in, there's places like Itch.io -- less people have the default expectation that only Steam matters. They're more open to distributing in different places, finding different audiences, not making APIs and technical decisions that make it difficult to be off Steam. It can be a healthier ecosystem if there are quite a few stores.

"People have this unrealistic expectation that a new store will launch and take half of Steam's revenue -- that's just not how things work"

"PC is an oddity in the games market in that there was one dominant platform. Mobile has iOS and Android, with consoles there are three main vectors, and different storefronts means that different customer bases and brands can hold up in a real way. If you think about a Nintendo collection of games versus a Microsoft collection of games, you already have a picture that they're different and their audiences are going to be a bit different. My hope for PC is that we can build up that kind of ecosystem."

Part of this perspective, she admitted, stems from her origins in the Flash space, where there were thousands of games portals. Developers had a wide variety of places to distribute, so if they didn't get featured on Kongregate or Newgrounds, perhaps they could gain exposure on another site.

"But when there's only one storefront, there's only one editorial slot," Greer said. "Let's break that up and I think it will eventually shake out better for most people involved."

Our time with Greer falls just a couple of weeks after yet another controversy around Steam's content policy. The marketplace had been host to a rape fantasy game, which Valve eventually removed, and the industry was once again discussing balacing store curation versus an open platform. Greer's stance was quite clear.

"We've had an open platform for years and we've had some pretty offensive games uploaded to Kongregate.com," she said. "But if they're against our policies, we'll take them down.

"It's really important is to have a very clear and explicit guideline as to what we do and don't support. If you go into our content guidelines, it is long, we give a lot of descriptions, and we try to give developers a lot of clarity. The worst possible situation is for a game to be uploaded and then taken down. We want developers to know before they come to the platform, or before they even start developing, what will be okay and what won't be."

Greer said this should extend beyond content to community and chat moderation, something Kongregate has built up years of experience around. Again, her stance was clear.

"It's a platform to play games, not a platform for free speech," she said. "Something like Twitter or Facebook has much more difficult problems -- we very much focus on player experience, and players should not be experiencing harassment or certain types of content.

"A policy of 'you can say anything' drives a lot of people away from games. We want to make games fun, and that does not do that."

"It's a platform to play games, not a platform for free speech"

Greer praised the rise of organisations like the Fair Play Alliance, which aim to protect players from harassment and abuse, as well as companies like Two Hat Security and Spirit AI developing advanced tools for tackling abuses of chat systems in ways human teams would be unable to manage.

But equally, she acknowledged that Valve is "dealing with really tough questions and issues" around its policies. Her concern is that allowing anything that "isn't illegal or trolling," as Valve has said, isn't clear enough for game makers to understand.

"I have a lot of empathy for them," she said. "We have a particular point of view, but as a smaller platform we're not having our edges tested as much.

"I don't want to speculate on all of the internal trade-offs that a company like Valve has to deal with and their experience. But clarity is something that's important to developers, particularly in a situation where they are such an important distribution channel. Ambiguity of what will work and what won't is a difficult thing to manage."

When we spoke to Epic CEO Tim Sweeney about store curation, he insisted the process needs to be human. Greer, however, believes a hybrid approach can be used -- pointing again to the mobile market as an example. Steam is inundated with new game submissions, but nowhere near as many as the App Store or Google Play.

Greer's understanding is that Apple operates "an entirely human process," while Android allows automatic uploads for new games but actively looks for unacceptable content through a mix of automated and human review. This is scalable for a platform as large as Google Play, where tools can identify potentially inappropriate games but a human is required to review them.

"There are things computers cannot judge," Greer said. "So eventually a human needs to see anything that is difficult. But you can do a lot of profiling what is likely a trusted developer, look for flags, and then you don't have to look at 100,000 things, you can just look at 1,000.

"If you rely entirely on a human process, you need a trillion dollars or you gate it very, very tightly. And that has negative consequences for developers because it very much favours incumbents and people who know somebody already at a store. But there are great games being made by newcomers all over the world who have never had the opportunity to come to something like GDC to promote their game.

"So that's why I believe very much in open platforms -- we've seen so many great games from such random places and such tiny teams. There are downsides to openness, but I think the pros are larger than the cons."