EA must lead on digital games transparency

Superdata analyst Joost van Dreunen issues an open letter to EA CFO Blake Jorgensen

Dear Mr. Jorgenson

Last week during Electronic Arts' earnings call, senior management released a glowing quarterly report card. Your company surpassed analyst expectations, largely by performing better in digital and the current momentum behind the next-gen console cycle. As the chief financial officer, you noted during the Q&A section of the call that retail data was becoming an increasingly poor way to evaluate the company's, and by extension the industry's, success.

No shit.

"You guys have heard me say this before, but I will say it again, and that is, be really careful using NPD data. It is becoming less and less valuable as more and more of the business is going digital"

Blake Jorgenson, EA CFO

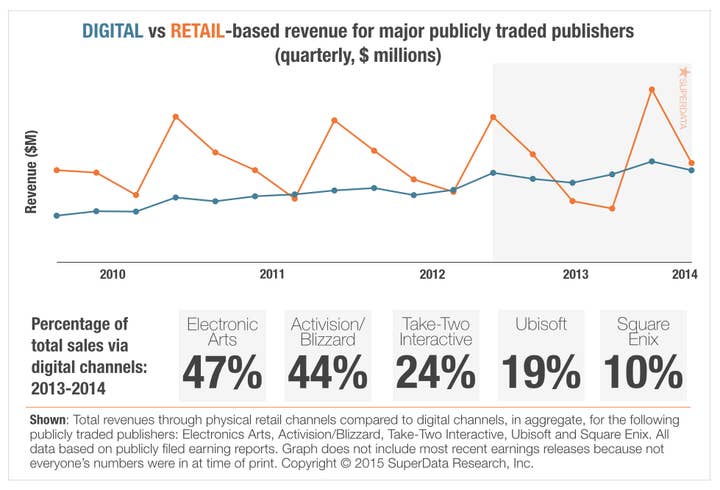

More specifically, my first reaction was: "Why are we even talking about this?" As a legacy publisher with more than half of its revenue coming through digital channels, EA is leading the pack. A close follower is Activision Blizzard with 44 percent digital earnings, and Take-Two Interactive makes about 25 percent of its money via digital distribution. Of course, in recent years several digital-only publishers like King and Zynga have entered the stage, further solidifying the notion that games, like music and video, are now primarily produced, distributed and consumed digitally.

With $49 billion in worldwide sales, digital games have been bigger than retail for some time now. It is unbelievable that in 2015 the CFO of a major game publisher has to remind financial analysts that looking at retail data alone is not going to give you the whole picture. If nothing else, it undervalues your firm's accomplishments. So I started to wonder why is it that people seem so unaware of the fact that digital games represents the dominant business model, and not retail?

People, what a bunch of bastards

A large part of the explanation for why digital games have such a difficult time being taken seriously is the inevitable inertia that comes from doing things a certain way for a long time. Specifically, managers at all levels in a company tend to outline their strategies and make their decisions based on the mental map they've created of the industry over the course of their career. Having become successful by doing things a certain way, it is generally very difficult for people to switch mindsets later on. Taking a conservative, risk-averse approach is often more desirable, especially when having to answer to shareholders. But digital games aren't some nifty new secondary revenue stream. Digital games are the industry's future.

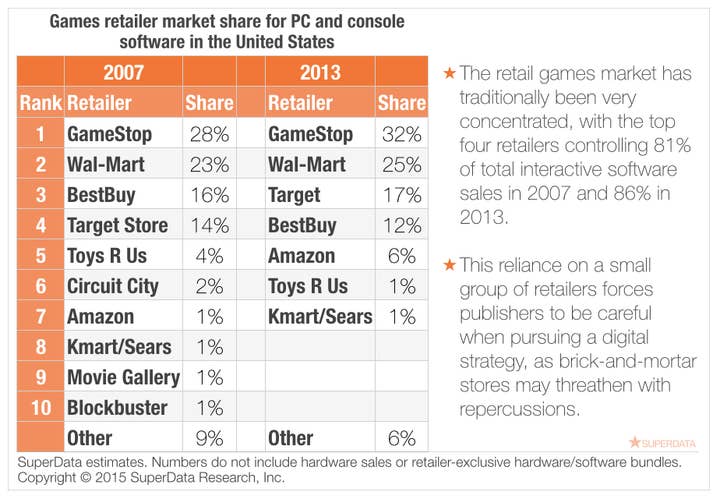

Secondly, large publishers such as yourself tend to be grandfathered into precarious relationships, especially with retailers. It does not take a lot of creativity to imagine a meeting between publishers and brick-and-mortar chains in which the latter seeks to leverage their control over in-store product placement and the mandate given to store clerks. Important here is also the increasing consolidation among games retailers, as the top four chains now control 86 percent of sales in the US.

Similarly, platform holders like Sony, Microsoft and Nintendo still rely heavily on their retail relationships, both for distribution and customer education. Insisting on pursuing an aggressive digital strategy would likely result in having retailers pushing competitors' products during the holiday season. Add to this the recent success for the interactive toys category, with Skylanders and Disney Infinity, and you begin to understand the complexity of the games industry's politics. Retail is and will continue to play an important part in the games industry and consumer experience, just like Apple stores are key to Apple's success.

Next, there is a lack of consensus on terminology and key performance indicators among legacy publishers that makes it difficult for them to compare relative success and market share without openly sharing data with direct competitors. Last year the UK's industry association Ukie tried, and failed, to get its members to share its digital sales and provide monthly industry reports. The main issue was the absence of several key publishers, skewing the data and making it largely meaningless. No doubt the ESA and other associations have considered mounting a similar effort. But this, too, seems to be a game that can only be played if everyone joins in.

"I would love to see companies like yours join the effort to make the global digital games market more transparent"

Investors and shareholders have a role in this as well. When Zynga went public, everyone wanted to sit on the front row. Following a string of disappointments, a lot of hedge funds and institutional investors have started to shun digital game publishers, mostly because they do not understand the business model. Case in point: when King went public, most financial firms drew a direct comparison with Zynga, even though these two firms aren't the same at all.

Finally, on the consumer side we also see some hesitation. Granted, not everyone manages to mount a successful digital transition and there can be ample problems with distribution, updates, customer service, latency and game play experience. But perhaps the biggest obstacle is their confusion why a digital copy of a game costs the same as it does in a store.

We have the data. We can build it.

Understandably, having to change how things are done is hard. But it is the traditional industry's own inertia that has allowed new-comers like King, Wargaming, Tencent, Nexon and Supercell to claim substantial market share. Adapting to these new market conditions is a good thing. In 2015, for example, all eyes are on Activision as it prepares the release of Heroes of the Storm, hoping that the strength of its existing franchises and accompanying lore will prove successful. Earlier, the publisher managed to claim the digital trading card space for itself with the release of Hearthstone by filling the need for a smooth, digital experience. The incumbent there, Wizards of the Coast's Magic: the Gathering, offers arguably an equally brilliant game play experience, but is hopelessly tied to the release schedule of its physical product. Is it a surprise then that Hasbro (which owns WotC) reported a 4 percent decline in its sales category while Hearthstone reported a record 25 million registered users?

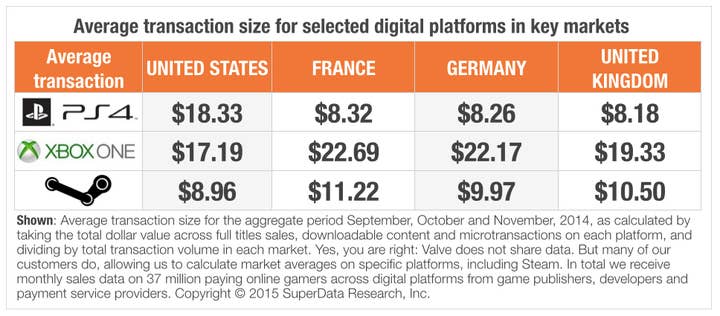

Perhaps more so than anyone else's it is the responsibility of all market researchers such as myself to make sense of the digital games market. I've argued before that answering questions for the digital games industry is different than doing so for the traditional retail-based industry. For one, there is no single dominant retail outlet for digital games. Sure enough, Apple and Google dominate mobile and Steam does so with downloadable PC games. But to describe the entire digital market, you need to successfully negotiate a lot more data deals than before. Add to this that the digital market is truly global, encompassing previously inaccessible markets like Brazil, Russia and Turkey, and you begin to understand why gathering such a dataset is difficult for market researchers.

The games industry is fascinating. It is volatile, full of unexpected successes and failures, fantastically expensive and, in my mind, the future of entertainment.

So, Mr. Jorgenson, if you'd like investors, shareholders, employees and your customers to better appreciate you and the rest of the games industry, perhaps it is time for some new habits. That way you don't have to answer redundant questions, and I, too, can do my job better. I would love to see companies like yours join the effort to make the global digital games market more transparent.

After all, isn't leading that what industry leaders do?

[Full disclosure: As a publisher of research on digital games and playable media, my firm, SuperData, works directly with both legacy and digital-only publishers.]